The Tahmazgerd church (the so-called Red church)

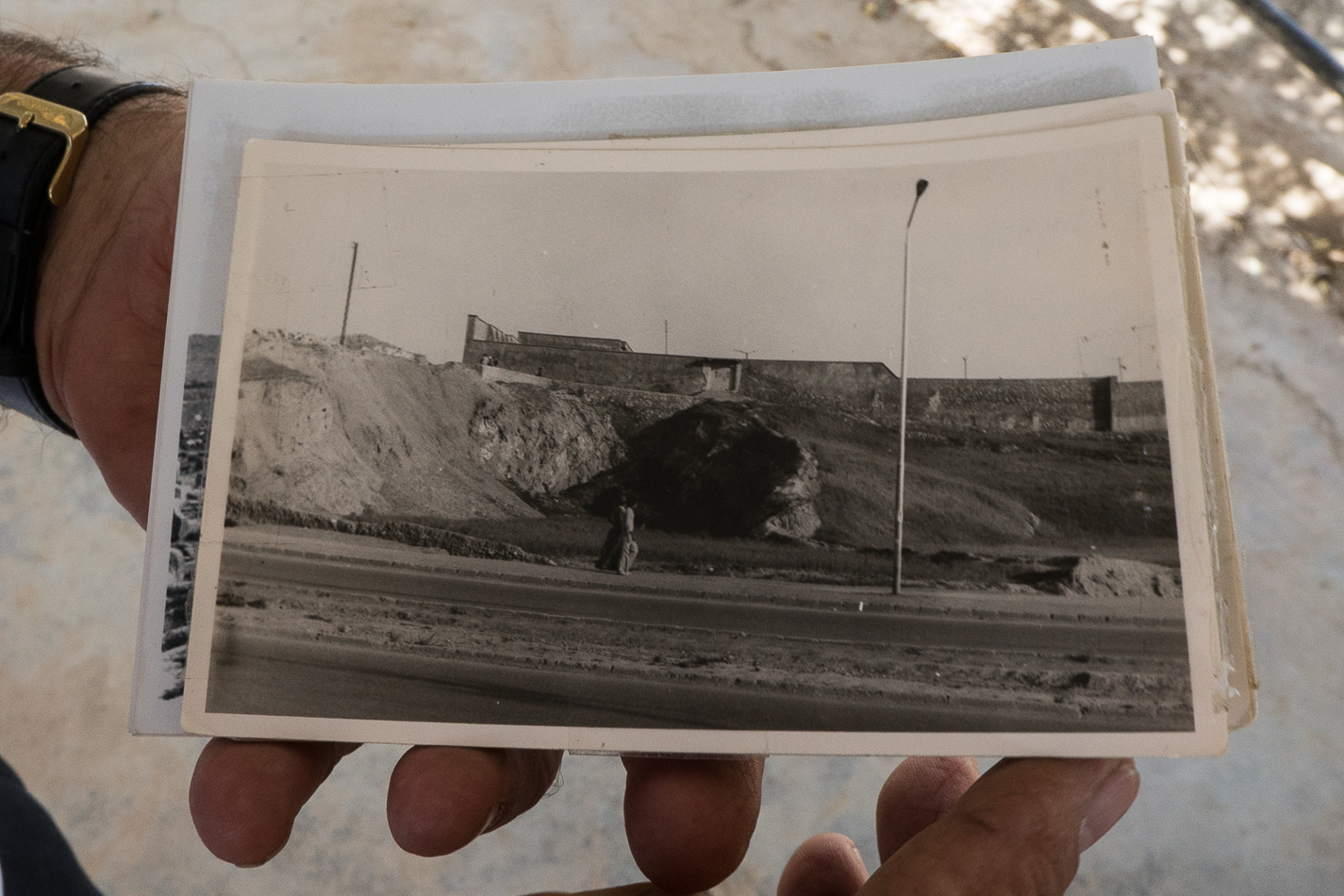

The Tahmazgerd church (the so-called Red Church) in Kirkuk is located at 35°28’6.08″N 44°23’1.37″E and at 344 metres altitude on top of a hill overlooking the city.

After the death of Yazdegerd II who, in 445, massacred 12,000 Christians and the entire clergy in Kirkuk, the Christians of Kirkuk erected a large martyrion in around 470 and began a commemorative service in order to “perpetuate the memory of the triumph of the victims.” The Tahmazgerd site to the east of the citadel, is thereby the most ancient Christian estate that can be seen in Kirkuk.

The church was named after the Persian officer, Tahmazgerd, who led the massacre. Having subsequently repented and converted to Christianity, he asked to be executed in the very same place where the Christians were sacrificed, thus becoming a martyr of the faith himself.

Location

Kirkuk is the capital of the province of the same name and is situated to the east of the Little Zab river. The river Khasa, a seasonal tributary of the Tigris, passes through the city to the east.

In the north-east of Iraq, the region where modern-day Kirkuk is located, is known in ancient history by the name of Bét Garmaï, formerly inhabited by the Garameans, possibly originating from “a Persian tribe which came to the region prior to Islam[1]”,but also possibly Ninevites and Chaldeans who spoke “Aramean certainly[2]”.

_______

[1]In Assyrie Chrétienne, vol.III, p.[1]15, Jean-Maurice Fiey, Imprimerie catholique, Beirut, 1968.

Demographics and geopolitics

The vast majority of the 1.2 million strong population of Kirkuk are Kurds. The rest of the population is made up of Turkmen (Shia and Sunni), Arabs (Sunni) and Christians (mainly Chaldean and a very small proportion of Armenians). There also used to be a Jewish community in the city which no longer exists. In 2018, there are thought to have been 5,000 Chaldean Christians in Kirkuk out of the 7,000 across the whole diocese.[1]

Kirkuk is an oil-rich city in the north of Iraq. Sectarian tensions flared in Kirkuk at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries and were exacerbated in the 1990s by the first Gulf war and the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003. Massoud Barzani, former President of the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan, laid claim to the city which was protected by Kurdish Peshmerga in June 2014 when ISIS tried to take the city.

A referendum on the independence of Iraqi Kurdistan which took place on 25th September 2017, included the province of Kirkuk, but by 16th October the Iraqi armed forces and associated paramilitary groups had retaken military and political control of Kirkuk.

_______

[1] Source: Monsignor Yousif Thomas Mirkis, archbishop of Kirkuk.

Fragments of the Christian history of Bét Garmaï and Kirkuk

Christianity came very early on to Bét Garmaï, as part of the evangelisation of Mesopotamia by the apostle Saint Thomas and his disciples Addai and Mari. Tradition names the first known bishop of Kirkuk as Theocritus.[1]Most likely originally from the Graeco-Roman world, he may well have sought refuge in Persia and developed his apostolate in Kirkuk at the very beginning of the 2nd century, between 117 and 138.[2]

In the History of Karka[3]“the most ancient Christian sanctuary in the city is believed to be the church built on the site of the house of Joseph, the first convert of Mār Māri.”[4] All traces have been lost of this sanctuary, which was not located inside the citadel of Kirkuk, but two kilometres away in Koria, today a district of the metropolis.

The Christian history of Kirkuk was marked by the persecution perpetuated by the Sassanid king Yazdegerd II, in 445, which caused “not only 12,000 deaths, but [also the loss of] the entire hierarchy.”[5] At war with the Eastern Roman Empire converted to Christianity, the Persian king considered Christians to be enemies of the kingdom and stepped up the imposition of Zoroastrianism across the empire. Six years after the martyrdom of the Christians of Kirkuk, he committed his troops to fighting against the Armenians who he defeated in the Avarayr plain. In this case, as in the precedent, Yazdegerd II not only failed to eliminate Christianity from the Persian Empire, but also started the cult of martyrs which is still today an essential part of Mesopotamian Christianity.

The Monophysite Christians (Syriac) of Bét Garmaï then had to fight against the intolerance of Barsaume, the Nestorian Metropolitan of Nisibe (Nusaybin), at the end of the 5th century, around 484/485. Those who refused to turn to Nestorianism and resisted were killed or forced to flee. Throughout the centuries and repeat crises, Nestorianism remained predominant in Bét Garmaï up until the constitution of the Chaldean church, in communion with Rome in 1553, which is said to have been popular with the Christians of Kirkuk very early on, although a fully-fledged local Chaldean church did not emerge until the 18th century.

_______

[1]Of Greek origin, Theocritus / Theocritos / Tocriti means “strength of God”

[2]Source: Monsignor Yousif Thomas Mirkis, archbishop of Kirkuk.

[3]Karka is the ancient Syriac name for modern-day Kirkuk

[4]InAssyrie Chrétienne, vol.III, p. 49, Jean-Maurice Fiey, Imprimerie catholique, Beirut, 1968

[5]InAssyrie Chrétienne, vol.III, p. 17, Jean-Maurice Fiey, Imprimerie catholique, Beirut, 1968.

History of the Tahmazgerd church

In 445, Yazdegerd II massacred 12,000 Christians in Kirkuk. After his death, the Christians of Kirkuk erected a large martyrion in around 470 and began a commemorative service in order to “perpetuate the memory of the triumph of the victims[1].”The Tahmazgerd site is the most ancient Christian estate that can be seen in Kirkuk.

The church was named after the Persian officer, Tahmazgerd, who led the massacre. Having subsequently repented and converted to Christianity, he asked to be executed in the very same place where the Christians were sacrificed, thus becoming a martyr of the faith himself. According to tradition, this place was the very hill where the religious estate and cemetery are found.

The church is also known as the red church in reference to the blood of the victims of the massacre. Although another explanation might be the geology of the hill made up of red earth. These two explanations are frequently linked.

Its primitive church might have been erected around 470 by the Metropolit Maroun, even if the existence of a monastery in Tahmazgerd is attested in 1607.

The martyrion church of Tahmazgerd was largely destroyed in 1918 during the first world war in the fighting which opposed the Ottoman and British armies.We do not know exactly who blew it up. The Turks to ensure the British didn’t get their hands on the weapons they had stocked in the church? The British, to destroy the Turkish arsenal? That said, not everything was destroyed.

The building was restored in 1923 but is no longer visible today. The dome of the ancient church has been covered over with tombs. The idea of moving the tombs to undertake the excavation work and reveal the church was contested.

_______

[1]InAssyrie Chrétienne, vol.III, p. 17, Jean-Maurice Fiey, Imprimerie catholique, Beirut, 1968.

Description of the Tahmazgerd site

Built on the top of a hill, the access to which is controlled by a barrier, the Tahmazgerd site is closed off by an old metal door which is opened with a large, ancient key.

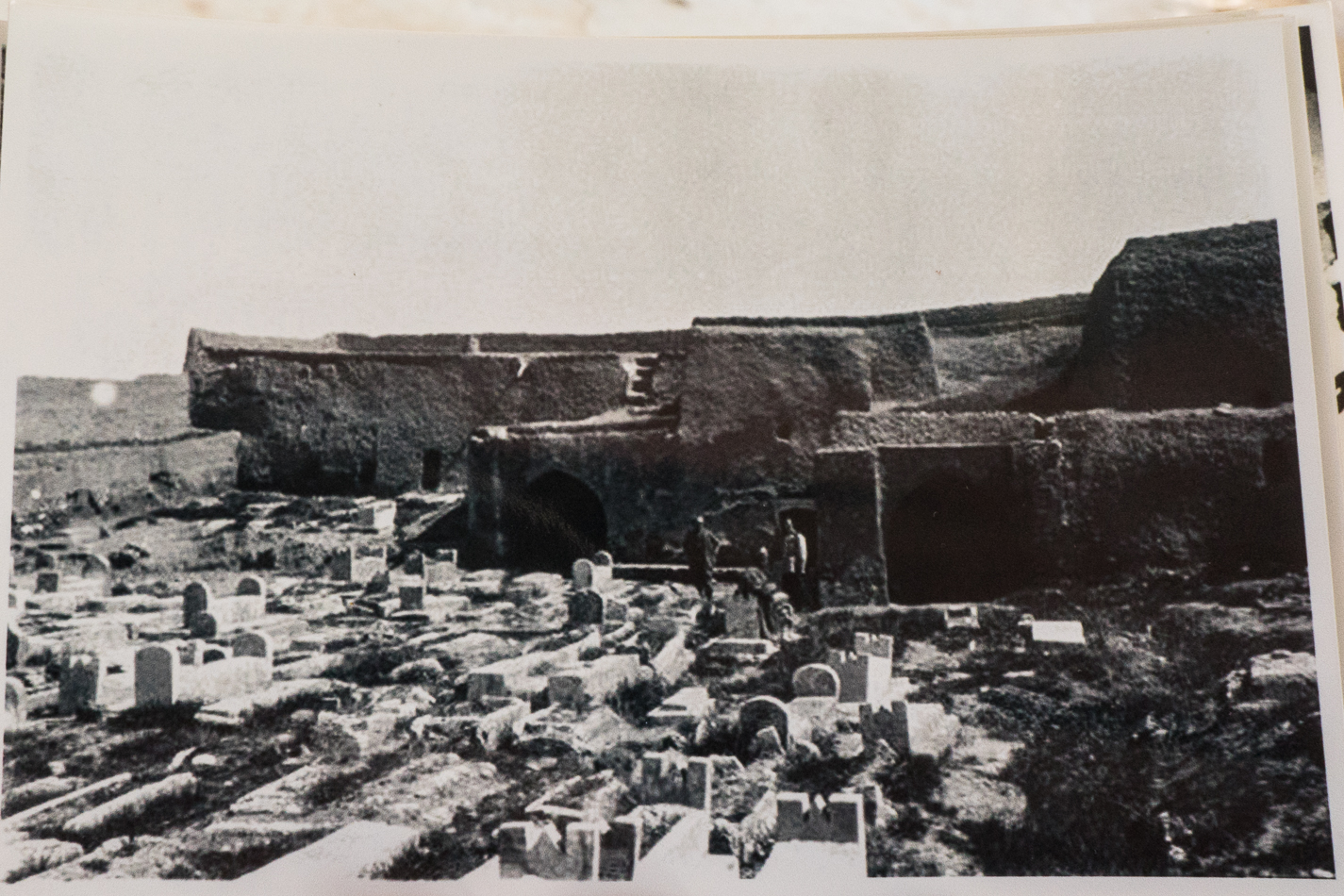

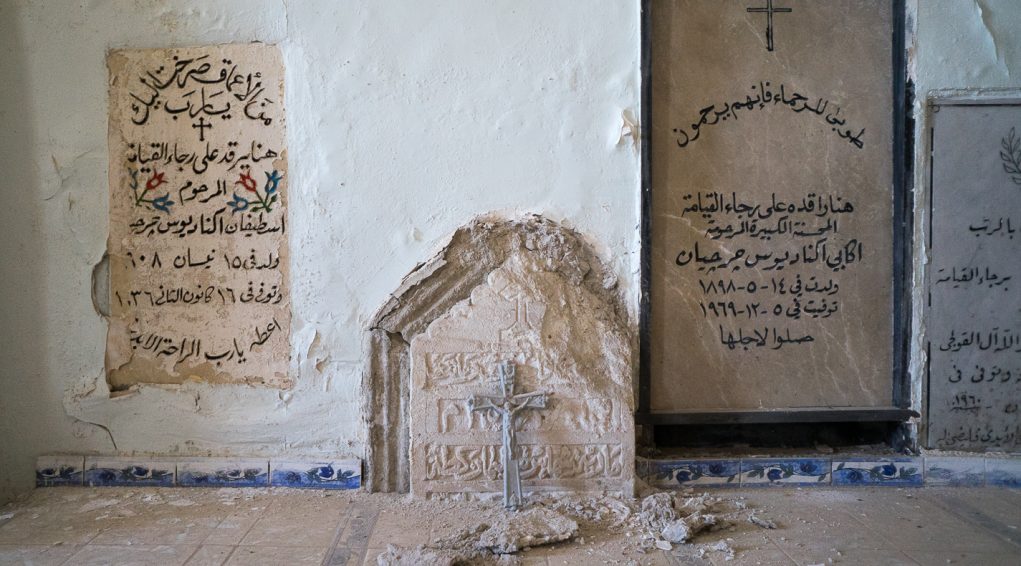

The Tahmazgerd estate is vast. It is first and foremost a large cemetery which occupies almost the whole surface area of the hill. The tombs from different periods of history bear inscriptions in Arabic and Syriac. They form a sort of catalogue of a whole swathe of local Christian history.

After passing through the entrance door to the site, the visitor walks along a shaded avenue for about 50 metres, before reaching, on the left, the church with its two naves and two altars, built in 1933. It contains the tombs of many dignitaries of the city. It is actually more of a necropolis than a church. It is a rare, even unique, case amongst Chaldean and Mesopotamian churches. The numerous headstones found here are almost all very ornately decorated. Some of these tombs date back to the same period as the church’s construction, others are relatively recent.

Of no architectural interest, this church was built in order to hold services, which had become impossible in the 1933 building.

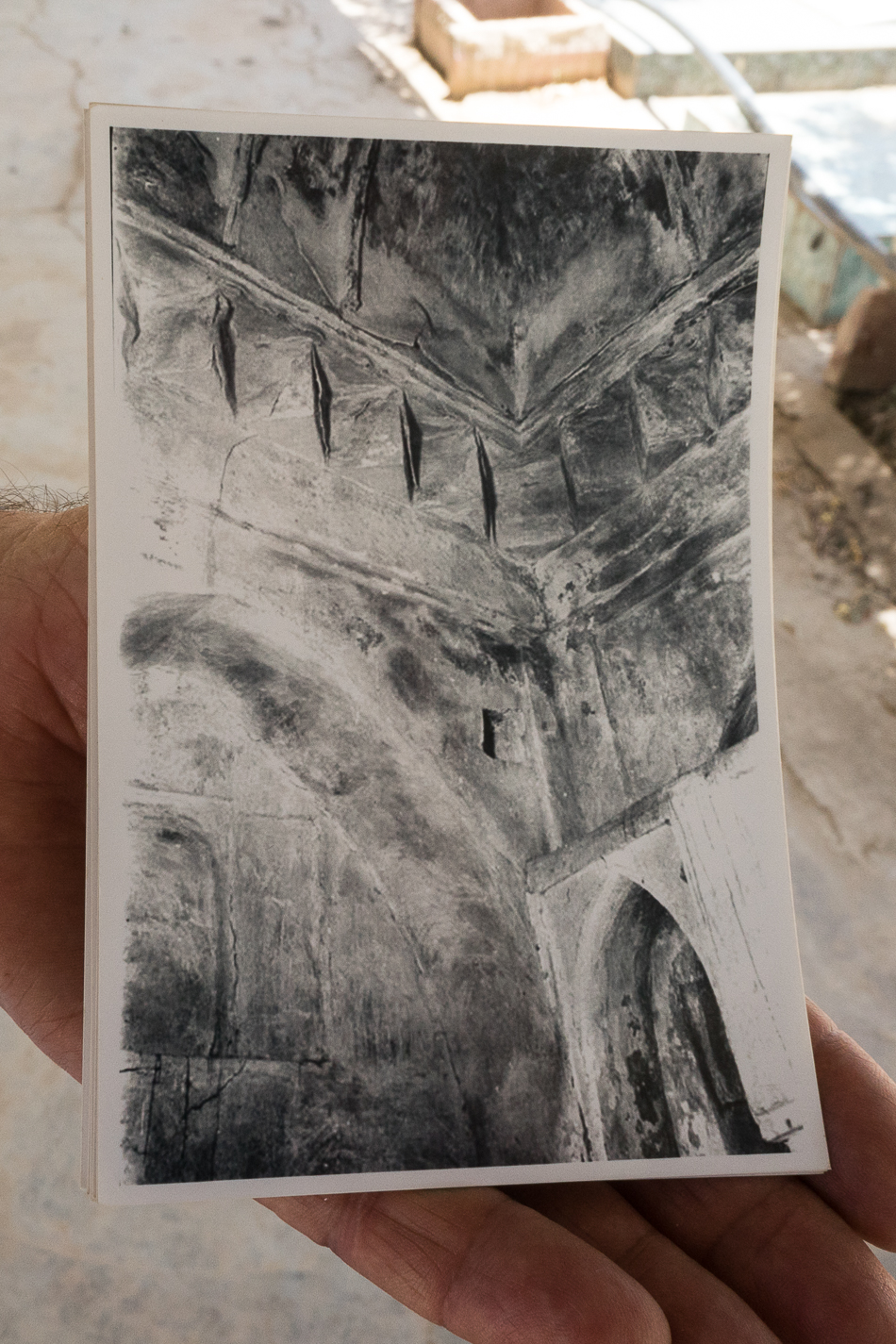

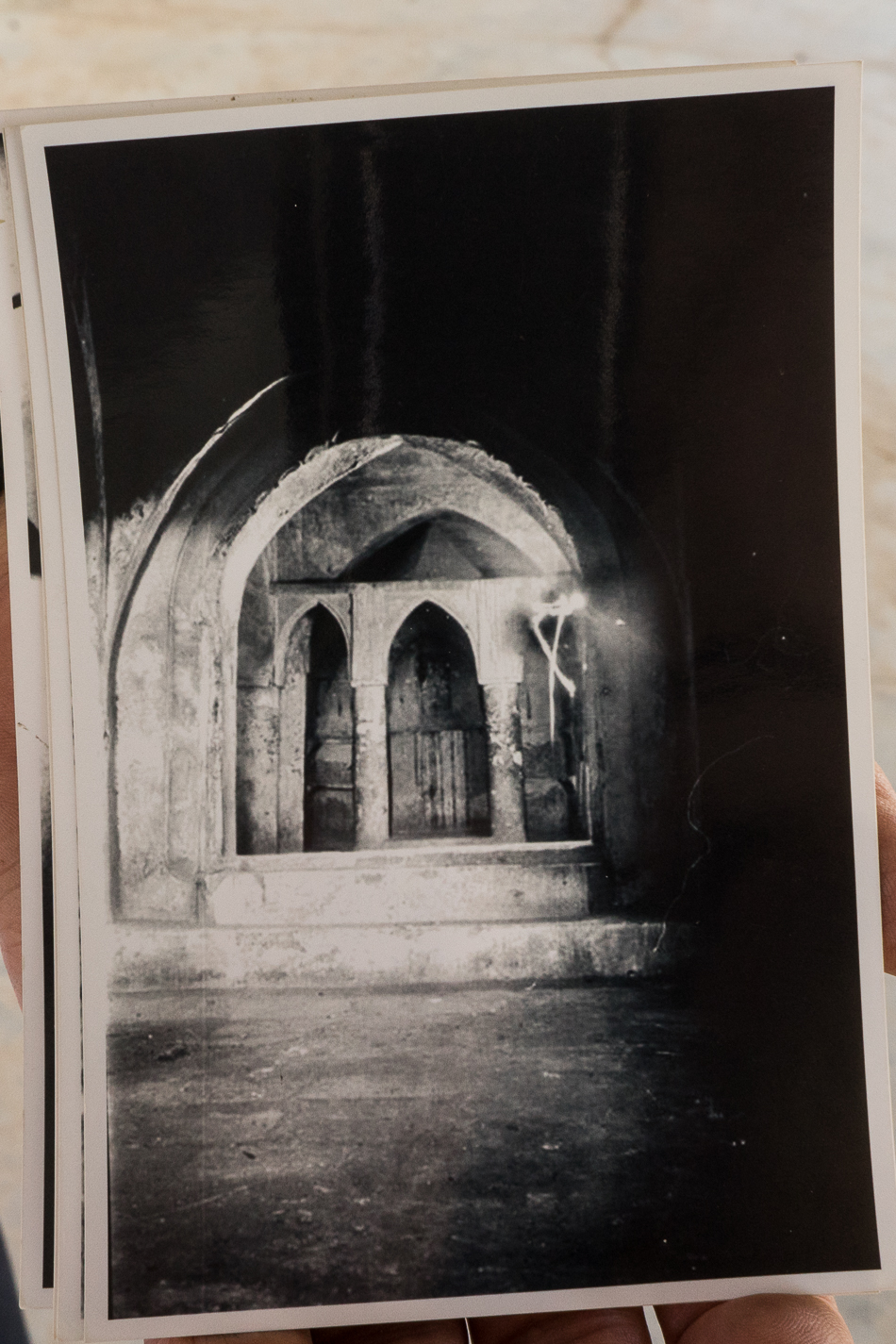

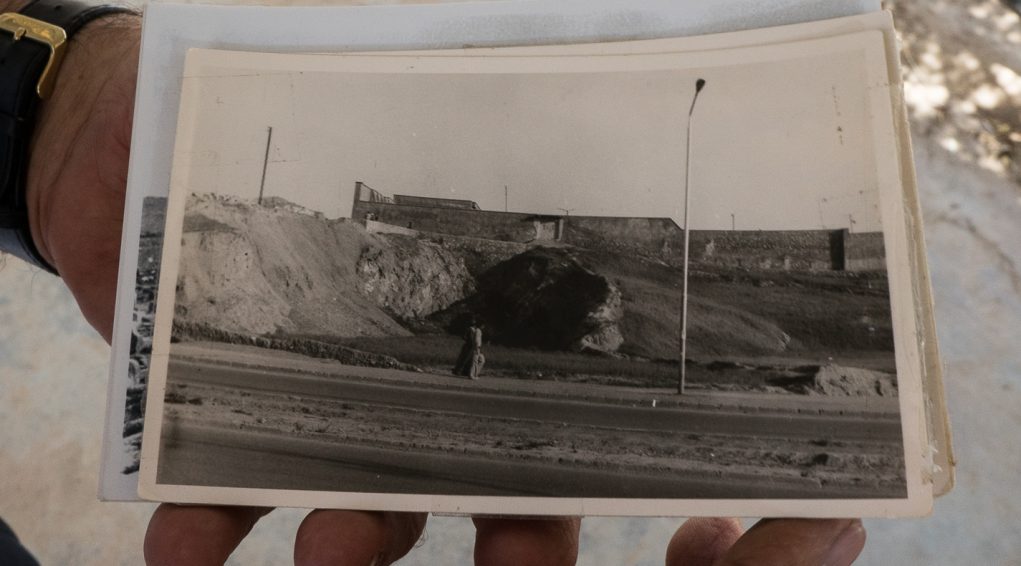

The Tahmazgerd estate used to be home to a large church which was partially destroyed during the first world war. The remains are no longer visible. The roof of the building is hidden, covered over by tombs. Rubble blocks the entrance. Although it can no longer be seen, we know that this church is found to the right of the entrance to the estate. A few old photos taken in 1948 attest to its existence. They also show a certain number of architectural features. However, this iconography is not supported by any more detailed and accurate documentation. Archaeological excavation could have a certain value in heritage terms, but the families of the people buried on the site oppose the idea.

Current status of the Tahmazgerd church

The cult of martyrs is still today an important part of Mesopotamian Christianity. Every year, on 25th September, the Christians of Kirkuk commemorate the martyrs of Tahmazgerd.

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute