The church Sourp Asdvadzadzin in Baghdad (Church of the Holy Mother of God, “Miskinta”)

The Armenian church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, also called Miskinta) lies at 33°20’45.66″N 44°23’11.88″E and 46 metres above sea level, in the district of Al-Mīdan in Baghdad, 400 metres from the eastern bank of the Tigris River. It is the oldest church in Baghdad still in use today.

The Armenian church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, also known as Miskinta) was built in 1639-1640 under the impetus of an Armenian artillery officer, who used to serve the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV. This officer, called Kevork Nazarian (Gog Nazar) seems to have played an important part during the siege and conquest of Baghdad in 1638.

The church has been renovated and rebuilt several times, particularly in the 19thcentury. Rebuilt in the years 1967-70, it seems to have progressively lost its primitive aspect.

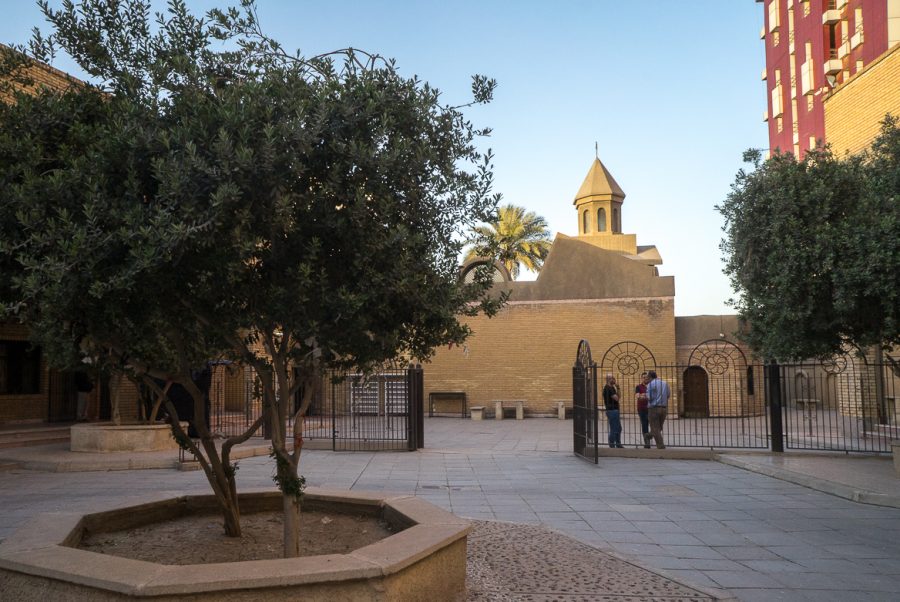

| Photo : Church Sourp Asdvadzadzin in Baghdad. View from the inner courtyard. March 2018. © Pascal Maguesyan / MESOPOTAMIA |

Location

The church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, also called Miskinta) lies at 33°20’45.66″N 44°23’11.88″E and 46 metres above sea level, in the district of Al-Mīdan in Baghdad, 400 metres from the eastern bank of the Tigris River.

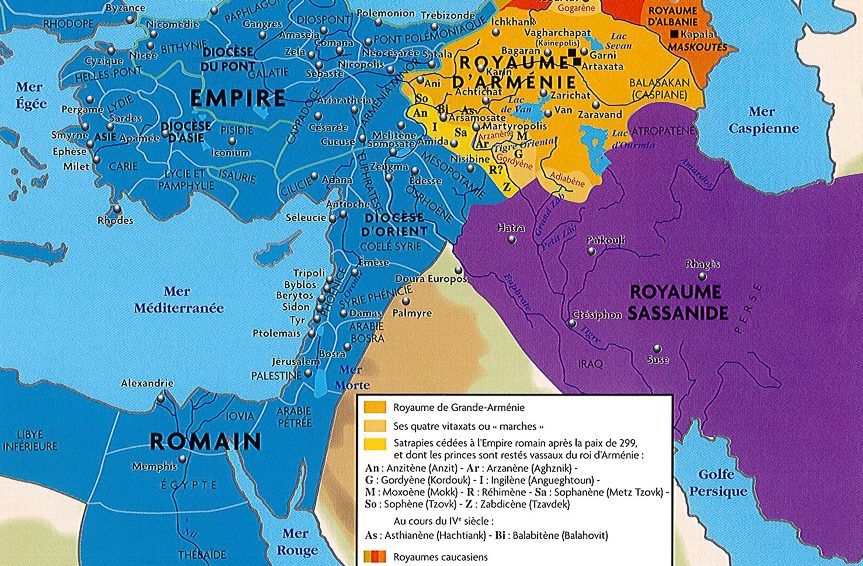

The origins of an Armenian presence in Iraq

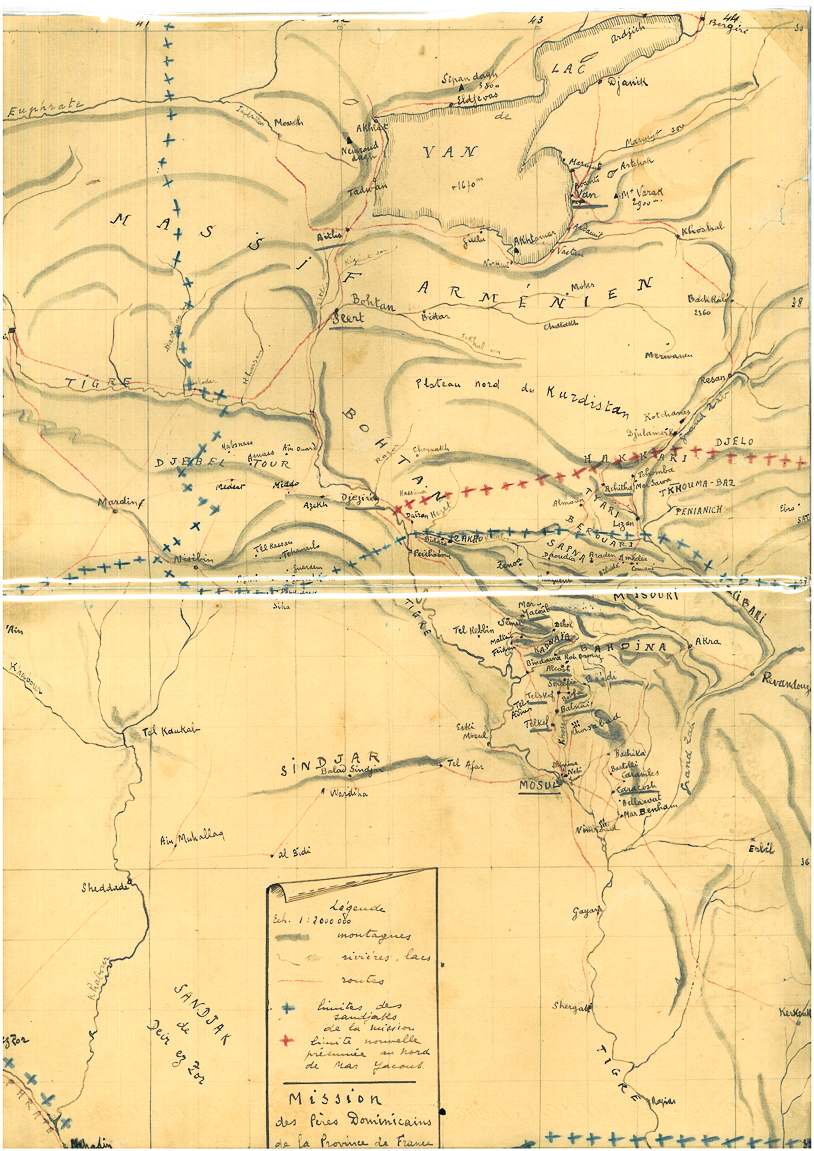

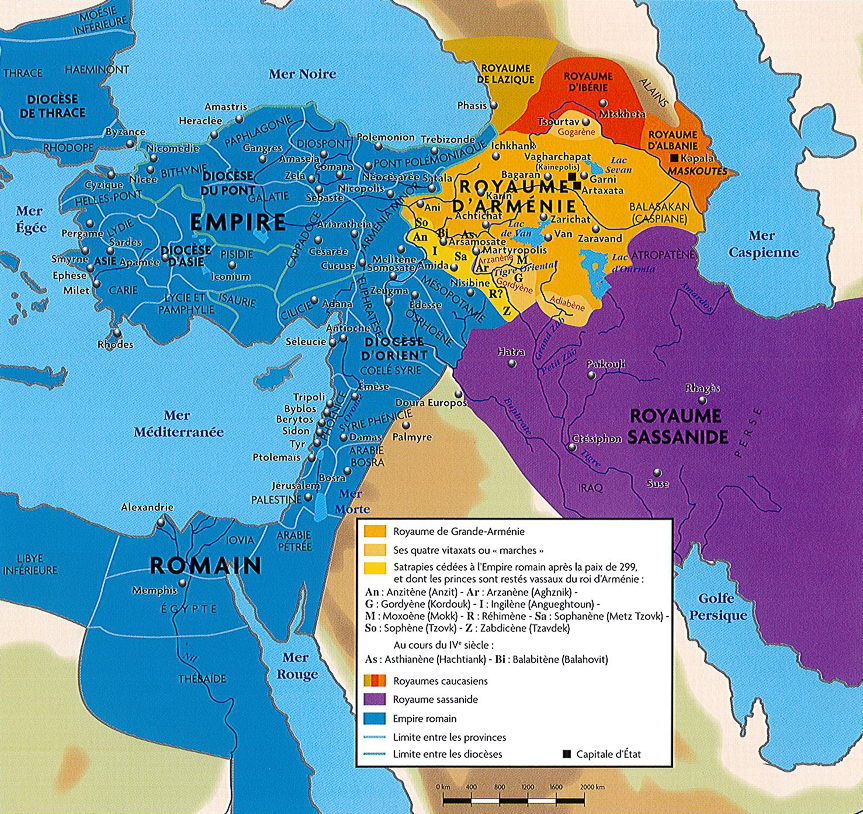

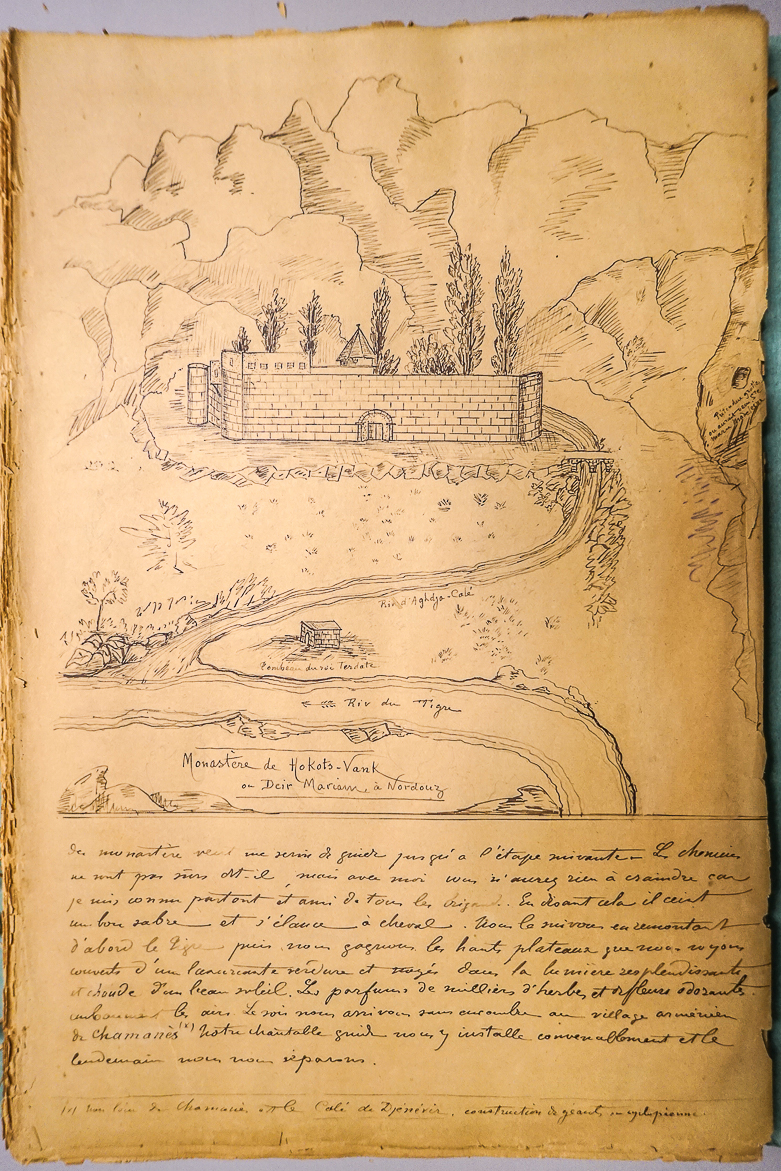

The origins of an Armenian presence in Mesopotamia have come along for centuries since Antiquity. In the 1stcentury before JC, the Adiabene kingdom (with Arbeles/Erbil as “capital city”) was part of the Armenian Kingdom of Tigranes II the Great. At the very beginning of the 4thcentury, the area of Abadiene, which was then the most southern territory of the kingdom of Armenia, has gone through a new evangelization’s phase, after Armenia became the very first Christian “state” in History, around 301.

«What also seems reliable is that there has been a meeting, around 328-329, between the only two Christian sovereigns in those times: the Roman emperor, Constantine the Great, and Tiridates III of Armenia. Constantine the Great confirmed Tiridates’ role in evangelizing the East. That is the reason why Armenian missionaries took part in evangelizing Mesopotamia and the Sasanid Empire, as related by the Greek historian Sozomen around 402: “Then, among the border people, the faith grew and worshippers increased in number and I do think that the Persians turned to Christianity thanks to the important relationships they had with the Osroenians and the Armenians[1](…)”».

In the 17thcentury, new Armenian communities settled in Iraqi Mesopotamia after that the Persian Shah Abbas I conquered Baghdad in 1623. In the early years of the 17thcentury, the Persian king forced the Armenian population of Julfa (former Armenian city in the Nakhichevan, on the northern bank of the Aras river) to exile. 12 000 Armenian people were then moved to New Julfa (Nor Djougha), at the gates of Isfahan, to take part in the development of the Safavid-Persian Empire’s new capital city. After Shah Abas died, the Armenians from Persian endured times of troubles. Lots of them moved to Mesopotamia and settled in Basra (south of nowadays Iraq), whereas some others set off to India.

When the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV regained control over Baghdad in 1638 by with the help of Armenian Ottoman soldiers (see chapter below), a new phase started for an Armenian settling in Baghdad. All along the Ottoman domination’s period and until the fall of the Empire at the beginning of the 20thcentury, the Armenians developed their institutions so much that by the end of the 19thcentury they were nearly 90 000 living in Iraq[2].

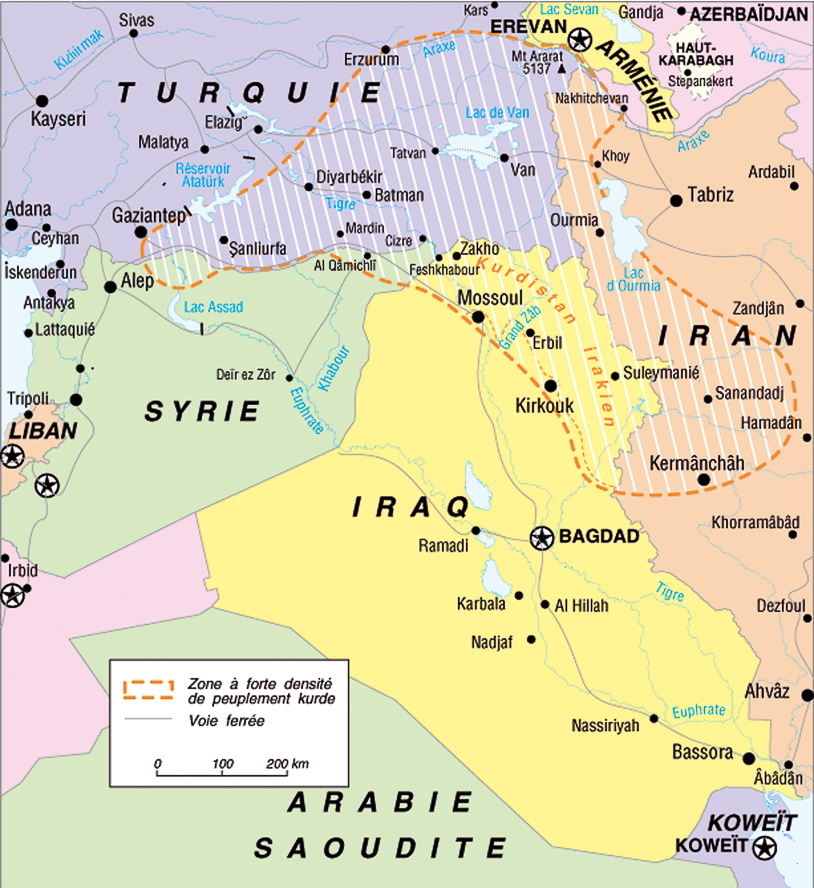

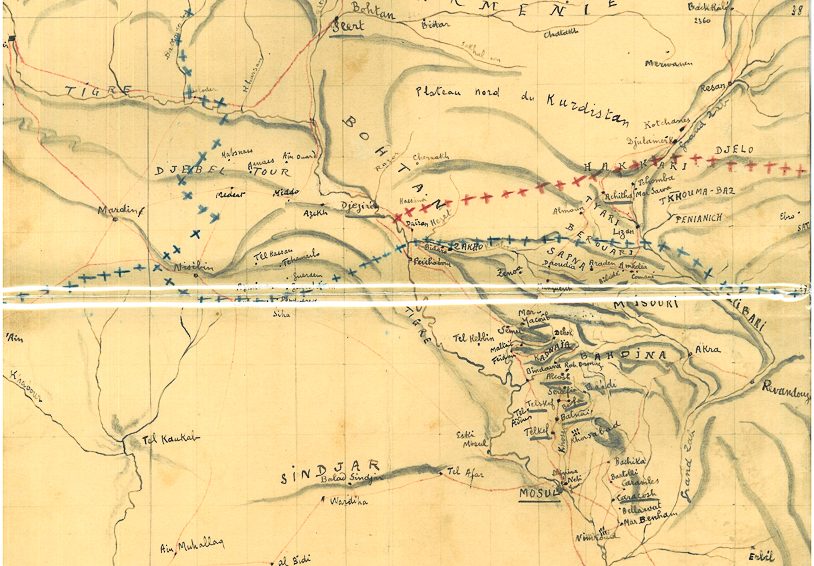

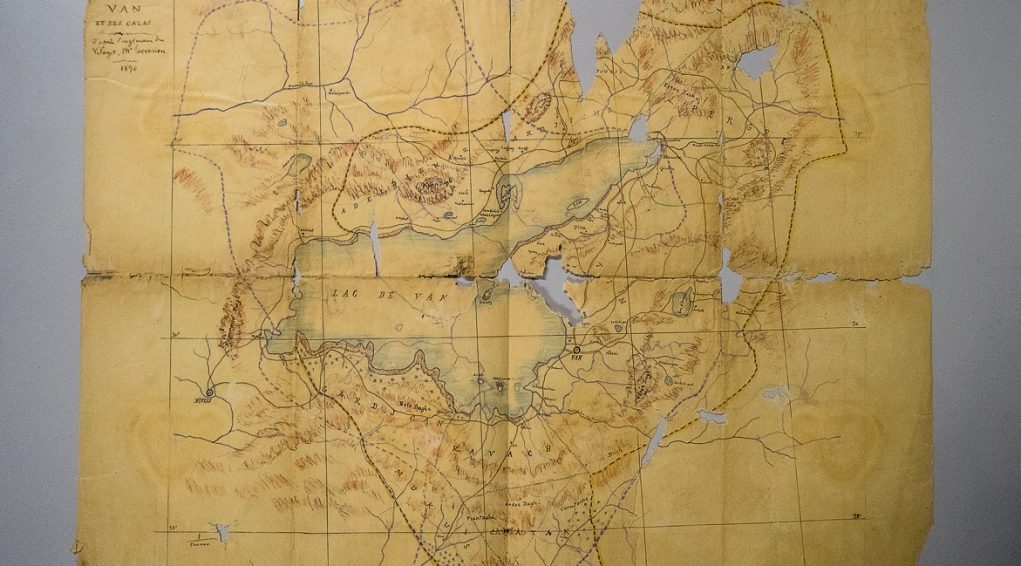

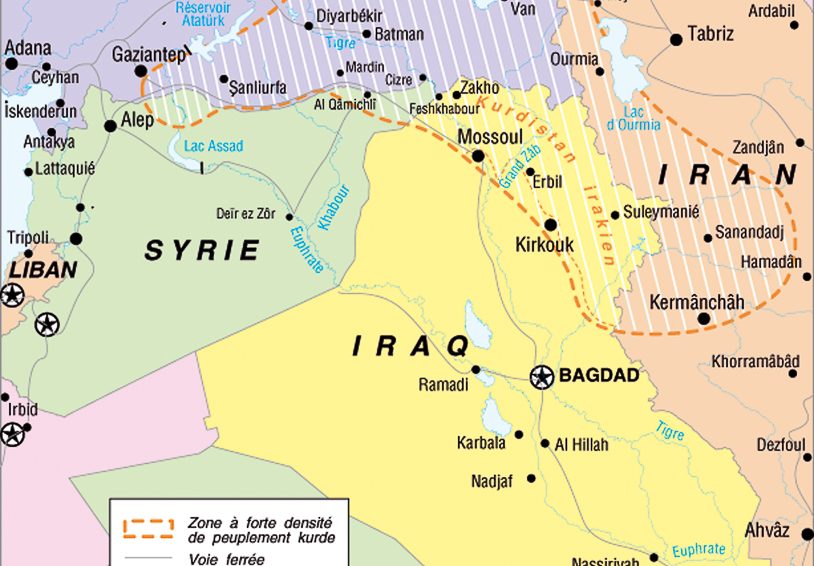

The genocide of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in 1915-17 was the last and terrible reason of their migration towards Iraqi Mesopotamia. Deported from the eastern provinces of the Empire, coming from the North (Diyarbekir) along the Tigris river, from the West (Ras-al-Ain) along the railway from Aleppo to Baghdad, or also from Van and then coming first through Persia, the Armenians arrived in some relegation areas such as Zakho, Avrest, Avzruk but also Kirkurk and Mosul.

About this point a terrible incident needs to be reported. In January 1916, over only 2 nights, more than 15 000 Armenian people deported in Mosul and around were exterminated by drowning, tight in batches of 10 and thrown in the Tigris River. A long time before this carnage, the German consul in Mosul, Holstein, sent on June, 10th1915 a telegraph to his Ambassador describing horrible scenes: “614 Armenians (men, women and children) were expelled from Diarbekir and taken to Mosul. They were all shot during their boat-trip (over the Tigris River). The keleks arrived empty yesterday. The river has been carrying dead bodies and human parts of bodies for a few days (…)[3]”.

Nowadays, the Armenians in Iraq mostly descend from people who survived the 1915 genocide. Rather discreet on the political scene, they were known for being loyal and developed their own educational, social and religious infrastructure.

On a religious point of view, the Armenians from Iraq are mostly members of the Armenian Apostolic Church (autocephalous church since its origin in 301), some are members of the Catholic[4]community and some others joined a small evangelic community.

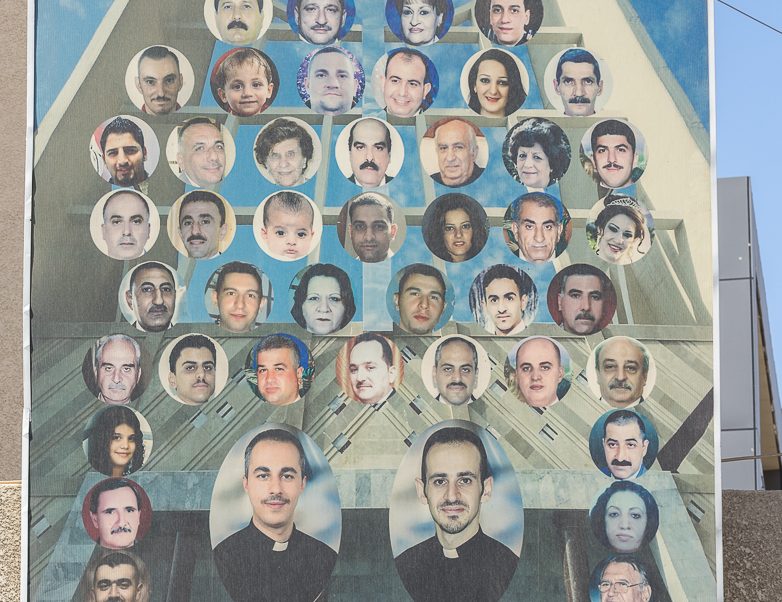

After Saddam Hussein’s regime fell in 2003, the situation worsened considerably. The attacks from Islamic and Mafia groups against Iraqi Christians also targeted the Armenians and their churches. On August 1st2004, the Armenian Catholic church Our Lady of the Rosary, in Baghdad, Karada district, was struck by a bomb attack. An Armenian church under construction was also targeted on December 4th2004. For nearly 20 years, these successive spates of violence set the tempo for Iraqi Armenians’ mass exodus. The battle of Mosul over the summer 2017 and the bombing intensity also affected the Armenian heritage. Before 2003, there were probably more than 25 000 Armenians in Iraq, whereas today the community leaders assert there are 10 000 to 13 000 Armenians still living in Iraq. Half of them are said to be living in Baghdad.

[1]In Arménie, un atlas historique,p.22 and map p.23. Publisher Sources d’Arménie, 2017.

[2]Source : Ambassade d’Arménie en Irak

[3]In « L’extermination des déportés arméniens ottomans dans les camps de concentration de Syrie-Mésopotamie ». Special issue of the « Revue d’Histoire Arménienne Contemporaine », vol. 2, 1998. Raymond H.Kevorkian. p.15

[4]On the Amenian Embassy in Iraq’s website, can be read the following: “in 1914, there were around 300 Catholic Armenians in Iraq. After WW1 and until 2003, the community numbered up to 3 000 members. Nowadays, the Armenian Catholics represent 200 to 250 families. They attend two churches: Our Lady of the Flowers, built in 1844, and the Sacred Heart of Jesus, built in 1937. In 1997, the main Armenian Catholic Church has been renovated and is considered as Baghdad’s largest church. The Archbishop Emmanuel Dabbaghian [was]the Hierarch of the Armenian Catholics in Iraq.”

History of the Armenian Church Sourp Asdvadzadzin

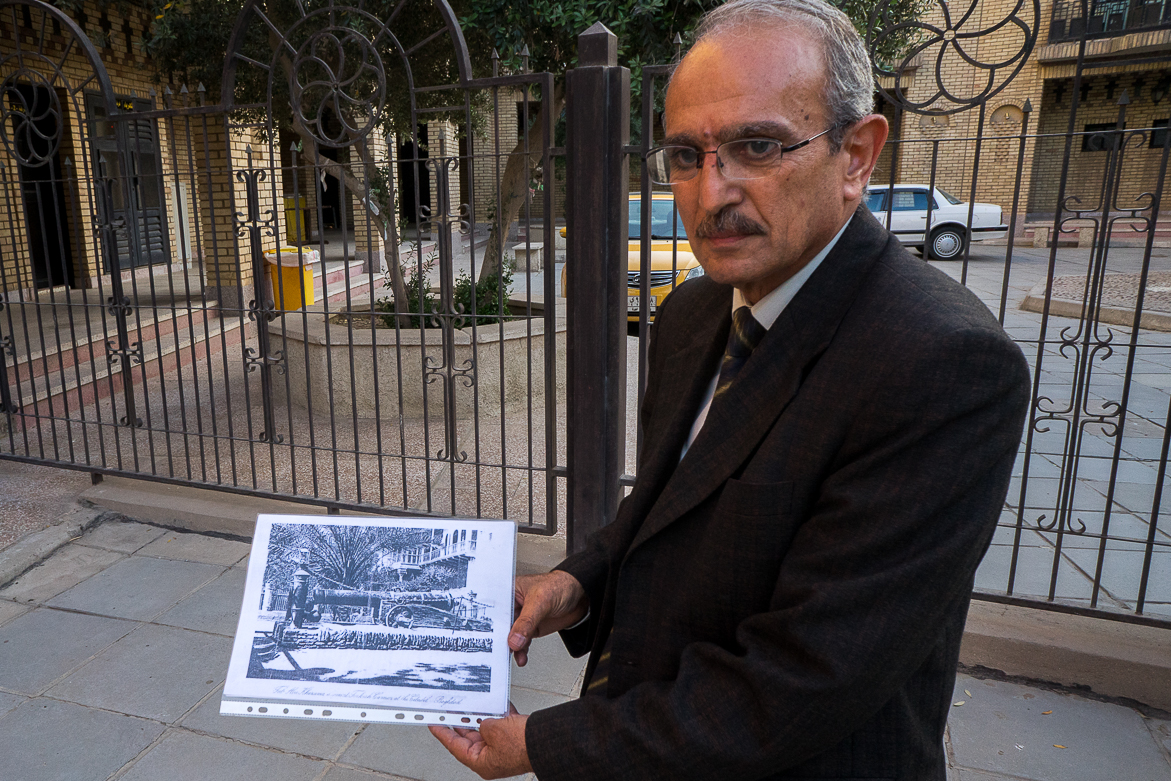

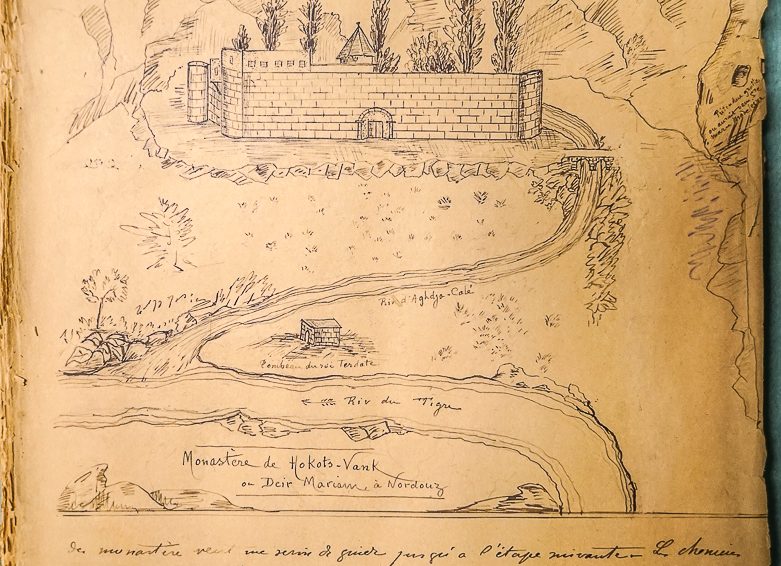

The Armenian church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, also known as Miskinta) was built in 1639-1640 under the impulsion of an Armenian artillery officer, who used to serve the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV. This officer, called Kevork Nazarian (Gog Nazar) seems to have played an important part during the siege and conquest of Baghdad in 1638. Thanks to his gunners’ unit, Baghdad’s fortifications have collapsed so that the Ottomans could conquer Baghdad. As a reward, he was granted the building of the church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, called Miskinta).

But the story does not finish here, as the hero managed to bring to Baghdad some of the relics of the “40 martyrs of Sebaste”, famous soldiers from the 12thRoman Legion, then quartered in Melitene (nowadays Malatya in Turkey) in Armenia Minor. The 40 soldiers were sentenced to be exposed naked upon a frozen pond near Sebaste (today Sivas in Turkey) so that they might freeze to death, because they refused to abjure their Christian faith. Those holy relics were placed by Kevork Nazarian in a niche, within the wall, at the right of the entrance door, in the church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, also known as Miskinta).

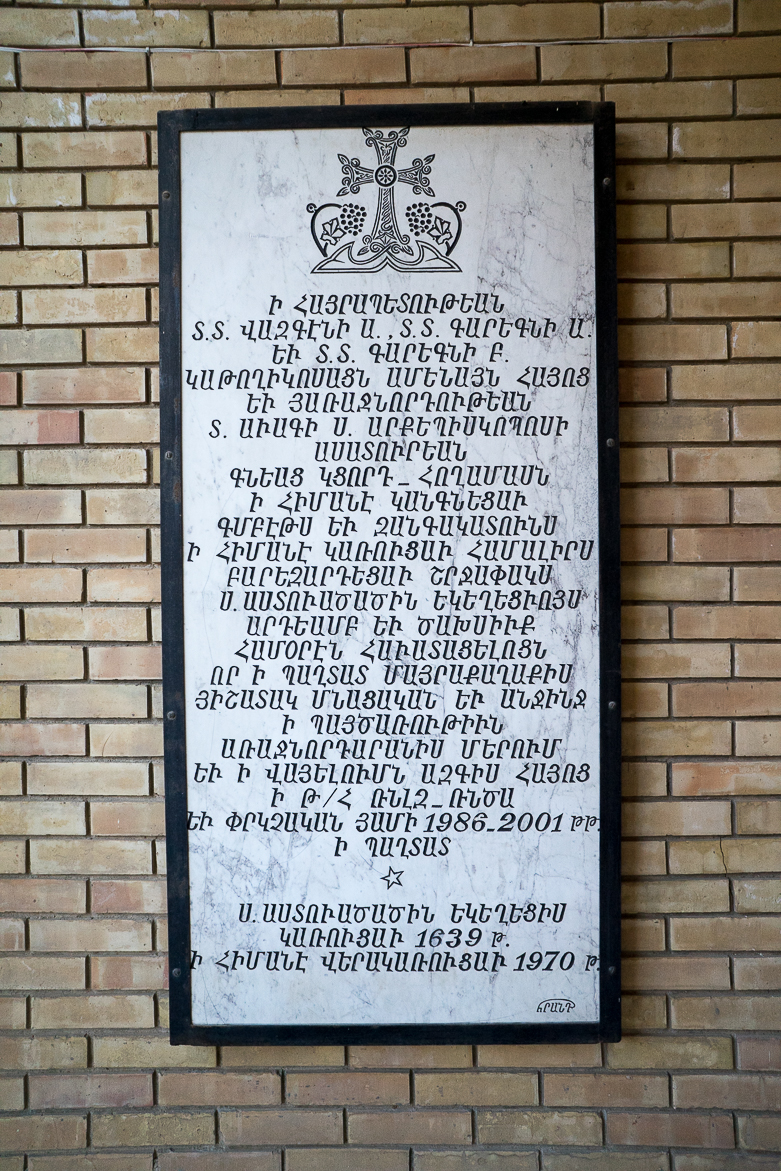

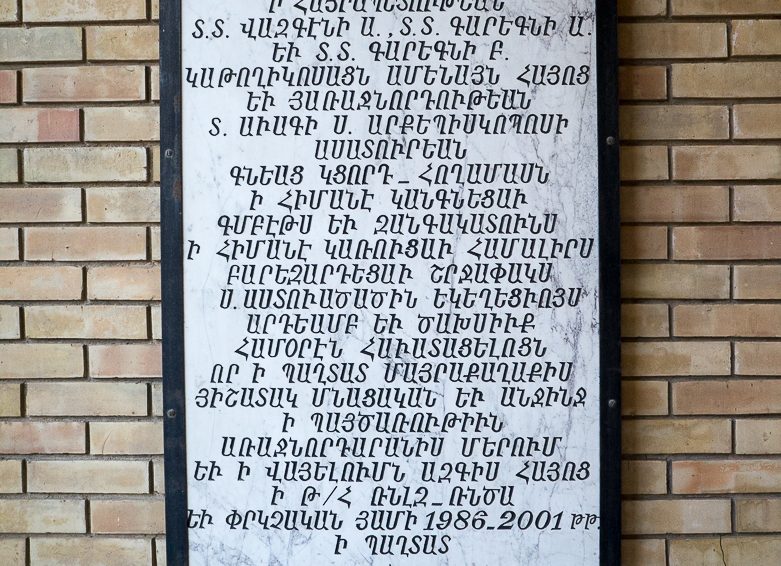

Between 1967 and 1970, the church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, also known as Miskinta) was deeply rebuilt and renovated during the pontificate of the Armenian Catholicos from Etchmiadzin Vazgen I and under the authority of the archbishop of Baghdad of the Armenians Asoghik Ghazarian.

During that renovation, the eight-sided marble reliquary containing the remains of the “40 martyrs of Sebaste” was rediscovered. The date 1663 was carved in Armenian letters on it. The reliquary returned at its primitive place.

For all these reasons, the Armenian Apostolic Church claims for the founding, the ownership, and the use of the church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, also known as Miskinta). However, those sources had been before opposed to by the Church of the East, who considered having founded the church before it turned Armenian. In his book, Les églises de Baghdad et ses couvents, Father Būtros Haddad stated that this church had been built between 1616-1628, that is to say about 10 years before its foundation in 1639 claimed for by the Armenian Apostolic Church.

During the Ottoman period which stretched over nearly 4 centuries, and up to the fall of the Empire in the early 20thcentury, the church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, also known as Miskinta) had to face many problems.

Occupied many times, the church would have been “liberated” – let’s say – against money. The controversy, still present today, reports that the church supposedly has been returned to the community that paid the best price, in that case, the Armenian Apostolic Church, to the detriment of the Church of the East. Popular legend or not, it is not nowadays the certificate of ownership of this church which is being contested, but rather the exactness about its Armenian foundation.

The church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, also known as Miskinta) has been renovated and rebuilt several times, particularly in the 19th century. Rebuilt in 1967-70, it seems to have progressively lost its primitive aspect.

Description of the church Sourp Asdvadzadzin

The church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, also known as Miskinta) is located within a religious compound, closed with a defensive wall and whose entrance porch is topped by a painting featuring a metal cross in Armenian style. Once through the porch, a small courtyard runs along the church’s northern façade, at the end of which stands a bell-tower with an octagonal roof, resting on a drum. Free of any ornament, this bell-tower shows a typical Armenian shape.

This courtyard leads to a wide inner courtyard, around which the church and its outbuildings are arranged.

From the esplanade, the architectural structure of the church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, also known as Miskinta) appears very clearly.

Bricks and concrete were both used as building materials for the reconstruction of the church.

The church’s roof is quite characteristic. It consists in 4 transversal barrel vaults, with a semi-circular window at the end of each vault. Above the sanctuary stands an octagonal drum dome, typical of religious Armenian architecture. Behind the dome, a protruding apse hosts the baptistery and the sacristy.

To get into the church, you need to cross the jamadoun (narthex), topped by a polygonal dome resting on a drum. The drum is adorned by a blind arcade and a clerestory, inside which the worshippers light votive candles.

The jamadoun gives access to the church itself, from the back of the nave, under the tribune where clerics and deacons sing Mass.

Single-naved building, the church is adorned with niches along the side walls, in which are embedded some stone plates, carved with crosses or Armenian inscriptions. One of them dates back to 1750.

A choir screen in ironwork separates the nave from the sanctuary. The sanctuary has 2 distinct and complementary parts, in respect with sacred Armenian architecture. Its lower part can be accessed to by the worshippers during the Eucharistic communion or the celebration of sacraments. Its higher part, hidden behind a red velvet curtain with a cross, can only be accessed to by priests, deacons and servants. On this rostrum stands the step-altar.

The treasure of the church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, also known as Miskinta) is undisputedly the chest with the relics of the “40 martyrs of Sebaste” (see chapter above). Placed in a marble niche, behind a finely wrought golden grate, this reliquary is adorned with Armenian inscriptions from 1663.

Worshippers, pilgrims and visitors do not come in the church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, also known as Miskinta) necessarily to revere those martyrs. This building is also a major shrine to the Virgin Mary, highly frequented by many Iraqi Christians and Muslims. During the feast of the Assumption (Dormition) of the Virgin Mary, on August 15theach year, the church Sourp Asdvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God, also known as Miskinta) is absolutely crowded.

Over the last few years, the Armenian community has erected new buildings to welcome the ever growing number of visitors. The church’s courtyard has also been enlarged and embellished.

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute