The Al-Tāhirā Chaldean church in Mosul

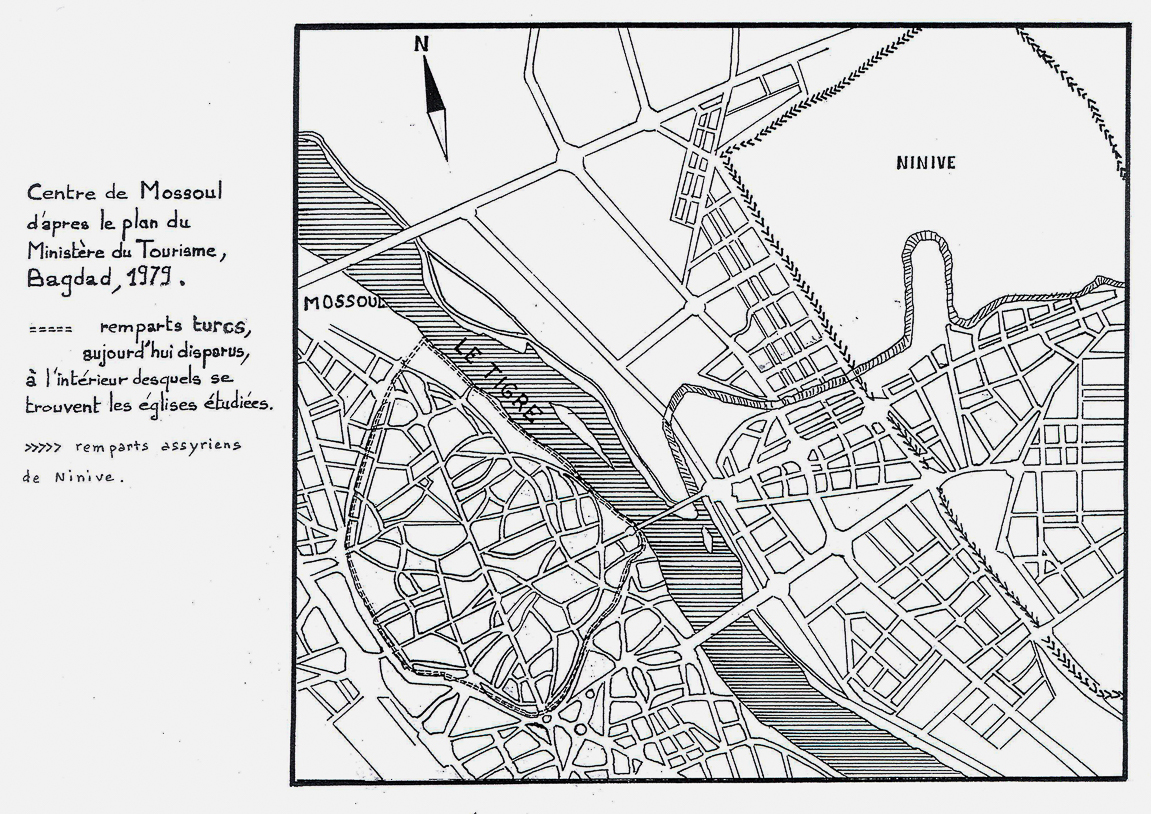

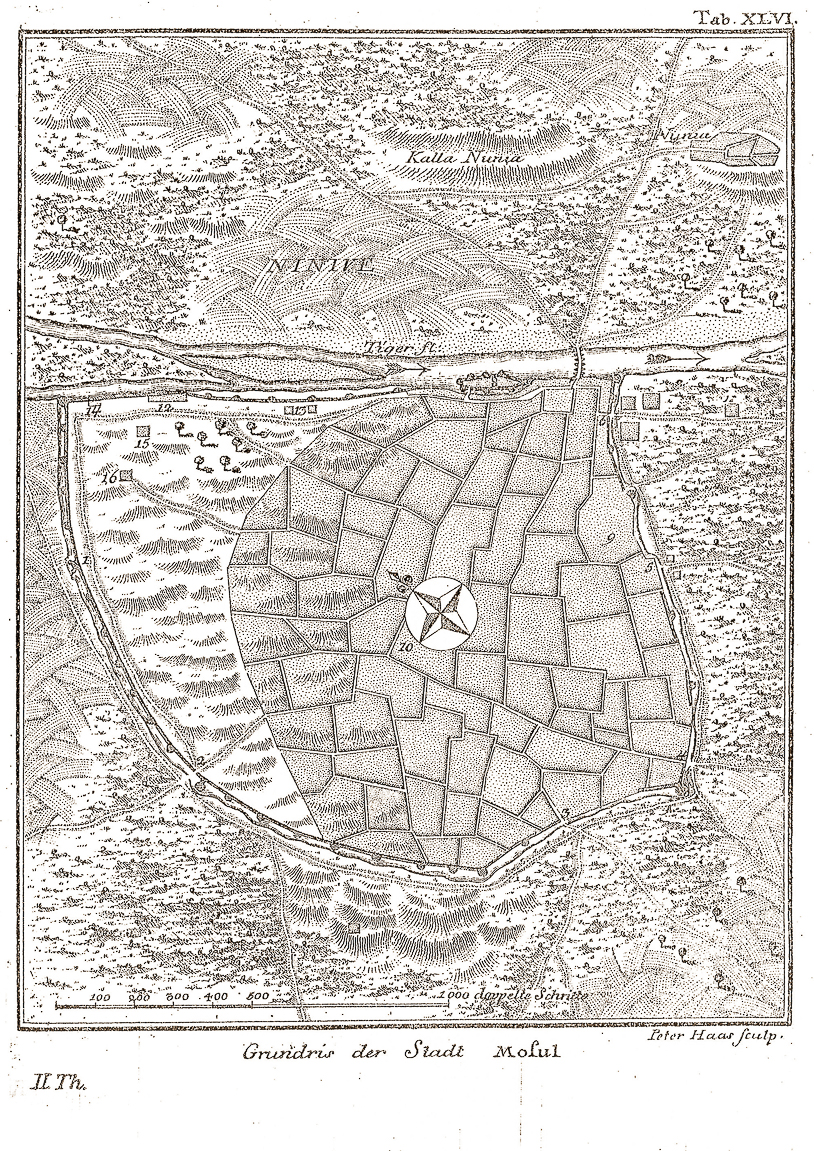

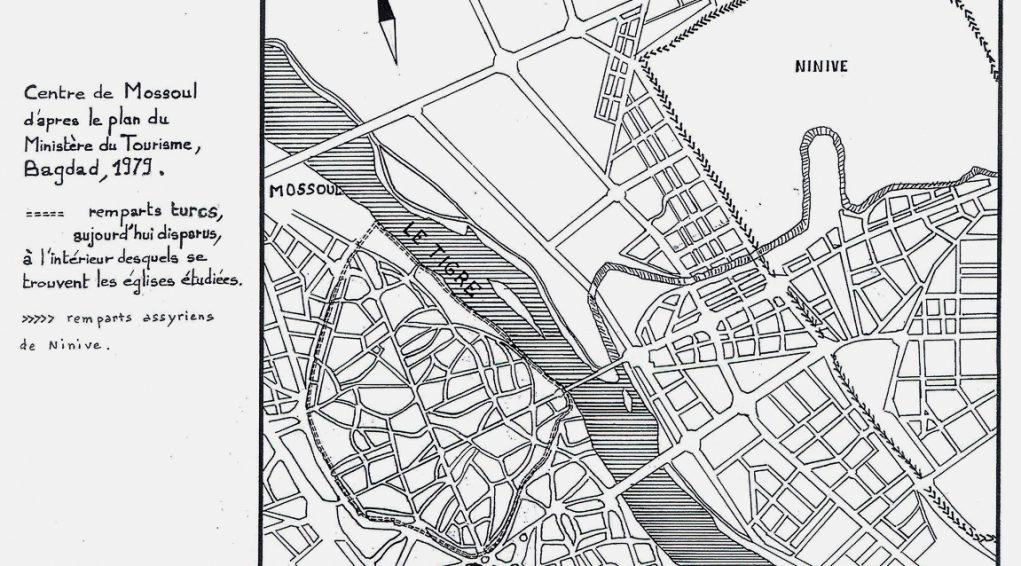

The Al-Tāhirā Chaldean church is located at 36°21’12.69″N 43°07’24.29″Eand 221 metres’ altitude,in the north of the old city of Mosul, formerly delimited by the Ottoman city walls on the west bank of the Tigris river, opposite the ancient city of Nineveh.

Any visitor looking for the Chaldean Al-Tāhirā church in Mosul should be aware that there are six churches of the same name in the city, each belonging to a different denomination.

The lower, more ancient part, dates from the 18th century, whereas the upper part, composed of additional floors, was transformed at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries.

The Chaldean Al-Tāhirā church is considered to be an 18th-century masterpiece; one of the most beautiful churches in the East. The interior of the church appears to have been spared from the worst damaged caused during the period during which ISIS occupied the city from 2014 to 2017. The intensive bombing mainly destroyed the upper parts of the building.

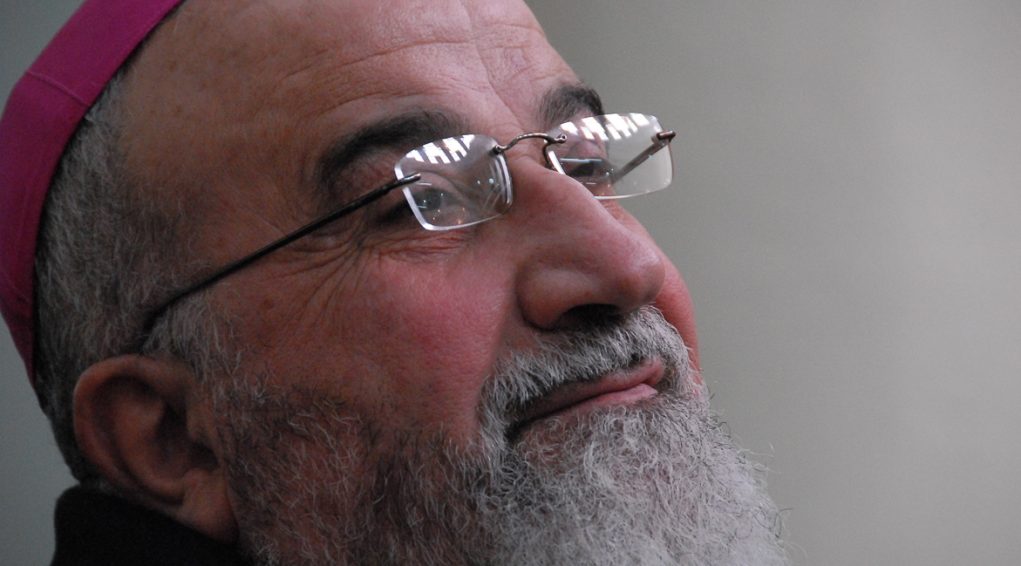

Pic : The Chaldean Al-Tahira church in Mosul. Extensive damage has been caused by ISIS and the bombing raids during the battle of Mosul. April 2018 © P. Pierre Brun Le Gouest / MESOPOTAMIA

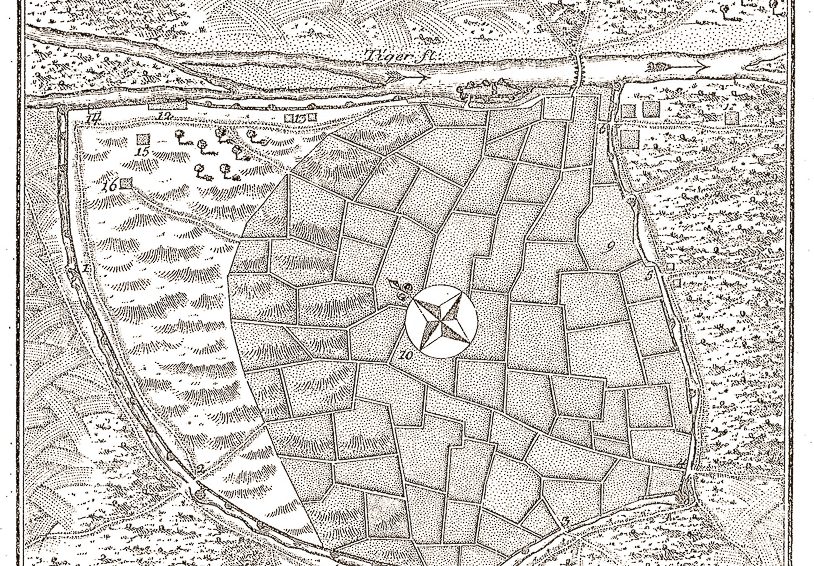

| Map of the Chaldean Al-Tāhirā church in Mosul © In “Les chrétiens de Mossoul et leurs églises pendant la période ottomane de 1516 à 1815”, Fr. Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p. Mossoul-Ninive, 1983, p.138 A. |

Location

The Chaldean Al-Tāhirā church is located at 36°21’12.69″N 43°07’24.29″E and 221 metres’ altitude, in the north of the old city of Mosul, formerly designated by the Ottoman city walls on the west bank of the Tigris river, opposite ancient Nineveh, 400 kilometres north of Baghdad. It is accessed via the Nabi Ğurğis road, close to the al-Imam Muhsin mosque.

Which Al-Tāhirā are we speaking about ?

The lower, more ancient part, dates from the 18th century, whereas the upper part, composed of additional floors, was transformed at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Close by is the Al-Tāhirā Syriac-Orthodox church, also known as “Tahira on high” (al-fawqaniyya)because the plot of land it is built on overlooks the Chaldean Al-Tāhirā church. The Syriac-Orthodox Al-Tāhirā church is also known as the “exterior” (al-harigiyya) because there is another Syriac-Orthodox church known as the “interior” (al-dahiliyya) also known as Tahira of Qala, which is located on a square with two Armenian Syriac-Catholic churches on either side (one ancient, one modern)… both called Al-Tāhirā !

The origins of the Chaldean Church

The Chaldean Church is a Catholic church, founded in the 16th century, further to a schism within the Church of the East. In 1552, several bishops, who had set up in northern Iraq, southern Turkey and northern Iran, contested the hereditary succession of the Catholicos of the Church of the East Shimun VIII. They elected in Mosul another Patriarch, Yohannan Sulaqa, abbot of Rabban Hormizd Monastery in Alqosh, who named himself Yohannan/John VIII. On 20th April 1553 Pope Julius III named him patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic church marking “its official birth.”[1][2]

Back in the Ottoman Empire, he set up his patriarchate in Diyarbakır (in south-east modern-day Turkey), 400 kilometres north-west of the monastery of Rabban Hormizd. Fighting openly with his rival Shimun VIII, Yohannan Sulaqa was arrested, imprisoned and murdered in 1555.

The foundation of the Catholic Chaldean Church was preceded a century earlier, in 1445, by a decree of union in Cyprus between Rome and some members of the Church of the East, who Pope Eugene IV already referred to as “Chaldeans”.

Up until the 19th century, the schism was particularly conflictual as many members of the Church of the East preferred communion with Rome.

The Catholic Chaldean Church’s see was transferred from Diyarbakır to Mosul in 1830, before the Metropolitan Yohannan VIII Hormizd was elected Patriarch.

Though they undisputedly counted as the majority among the estimated 1,200, 000 Christians in Iraq before the first Gulf war in 1991, the Chaldeans numbered 750,000 in the last census in 1987, compared to 300,000 Assyrians (Church of the East and former Church of East). The total number of Christians in Iraq then amounted to 8% of the total population. How many are there today? The information gathered by correspondents working with the charity MESOPOTAMIA confirm the demographic collapse reported by all the communities visited. There are thought to be less than 400,000 Chaldeans in Iraq, living in Baghdad, Kurdistan, the Nineveh plain and Basra. In fact, Christian communities in Iraq have had to face an uninterrupted stream of disasters since the country’s independence in 1933. Even the start of the 21st century offered no respite, with the American invasion in 2003, the UN embargo, and the violence and persecution by Islamic fundamentalists and organised criminals who have targeted Christian communities since the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime.

Today, the Chaldean Church is composed of a diaspora spread across countries in five continents: United States of America, Europe, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the former USSR in particular in Russia (Moscow, Rostov-on-Don), Ukraine, Georgia (Tbilisi), Armenia (Yerevan).

_______

[1]In « Histoire de l’Église de l’Orient »,Raymond Le Coz, Cerf, September 1995, p. 328

Fragments of the Christian history of Mosul

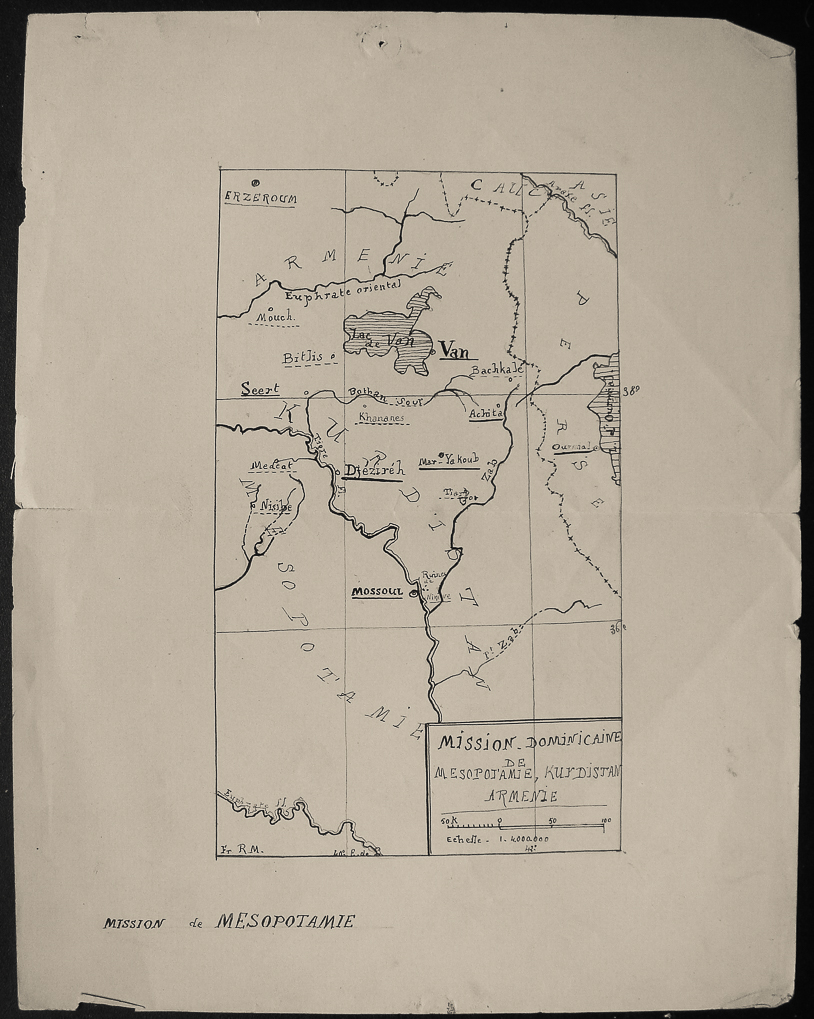

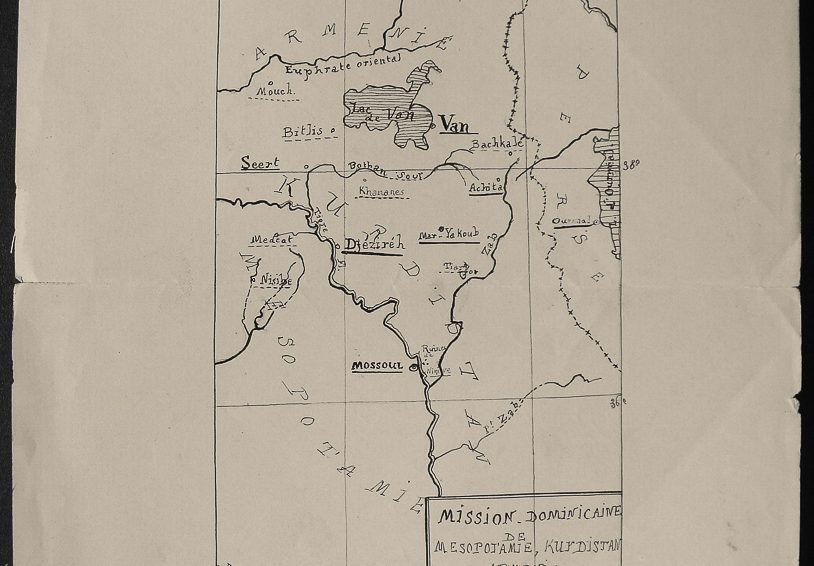

This chatper is largely based on the work of Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux o.p. who lived in Iraq for 14 years from 1968 to 1983 as part of the Dominican mission for Mesopotamia, Kurdistan and Armenia, based in Mosul. See, two books by Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux, in particular: « Va à Ninive ! Un dialogue avec l’Irak », Éditions du Cerf, October 2000; and « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Éditions La Thune, Marseille, July 2015.

Mosul “remains a Christian metropolis,”[1]as attested by its history, and its ancient and modern heritage, which persists despite recent catastrophic events.

Although the first archdiocese is attested to in 554,[2]it is also important to take into account the Paleo-Christian apostolic tradition. “Three churches are proud to be founded on houses where apostles are said to have stayed. The Sham’ûn al-Safa’ church, built during the Atabeg period in the 12th – 13th centuries, is said to be built where Saint Peter stayed during his visit to Babylonia and the Mar Theodoros church is connected to the visit of the apostle Bartholomew.As for the apostle Saint Thomas, the house where he was shown hospitality on his journey to India, became a church.”[3]The church in question is the Syriac-Orthodox church Mar Touma described herein.

The first church attested to in Nineveh (modern-day Mosul-East) dates back to the year 570. It is the Mar Isha’ya church which is even mentioned in the “Chronicle of Seert”. This confirms a pre-existing Christian community. In the 7th century the Syriac-Orthodox Mar Touma church was also known of. From the 7th century onwards, the Mar Gabriel monastery was the seat of one of the Church of the East’s most important schools of theology and liturgy. The Al-Tāhirā Chaldean church was built on the site of this monastery in the 18th century.[4]

Over the centuries, through successive councils and conflicts, a multitude of churches of different denominations, including the Armenian and Latin churches, were formed.

Of these various fragments of history, the Muslim conquest must be cited as one of the most important. Mosul fell in 641 and the Christian members of its population became dhimmis, with (limited) rights and (stringent) obligations based on their religious identity. This status remained in force up until the 19th century and was abolished in the Ottoman Empire in 1855. Despite this abolition, Christians (and Jews) still remain defined by their dhimmistatus which governs denominational relations in public life and attitudes in almost all Muslim countries. It is still legally enforced (in Iran).

In the 7th and 13th centuries, at the height of the Seljuq period, the Atabeg dynasties imposed their rule throughout Iraqi Mesopotamia and made Mosul a centre of power. At this time, Syriac-Orthodox Christians persecuted in Tikrit fled to the Nineveh plain and Mosul, where they established their community and founded the Mar Ahûdêmmêh (Hûdéni) church. “At the end of the 20th century due to below-ground flooding throughout the neighbourhood, the Mar Hûdéni church located well below ground level was flooded and had to be abandoned”.A new church was built right on top of the old one. Thankfully, the royal door in the Atabeg style, described by Father Fiey as a “jewel of 13th century Christian sculpture”,was transported to the new church and given pride of place. [5]

Following on from the Atabeg, the Mongol Houlagou Khan, took Mosul but spared the city from destruction and from the massacres committed in Baghdad in 1258, thanks to the “cunning governor of the city, Lû’lû’, of Armenian origin.”[6]The following century was nonetheless a tragic one.“Christian persecutions peaked under Tamerlan, whose armies ravaged the Middle East in the first years of the 14th century and exterminated the Christian populations. No other eastern Christian church underwent anything close to this type of eradication, the community in Iraq is well placed to claim the first prize in martyrdom.”[7]

In 1516, Mosul fell into the hands of the Ottoman Turks for the first time, but it was not until the following century that they established a dominant presence in Iraqi Mesopotamia that was to last for four centuries after the conquest of Baghdad in 1638 by the sultan Murad IV.

In the 16th century Mosul was a major centre of Christian influence. It was here that the schism of the Church of the East took place, with the election of Yohannan Sulaqa as the first patriarch of the Chaldean church. Abbot of Rabban Hormizd Monastery in Alqosh, he took the name Yohannan/John VIII and travelled to Rome to profess the Catholic faith. On 20th April 1553 Pope Julius III named him patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic church marking “its official birth.”[8]After Diyarbakır (in the south-east of modern-day Turkey) and before Baghdad (in 1950), the seat of the Chaldean church was established in Mosul in 1830, with the election of Jean VIII Hormez as the metropolitan of Mosul.

In 1743, the Christians of Mosul played an active role in defending the city during the 42-day siege laid by the Persian Nâdir Shâh who had already looted and ransacked the plain of Nineveh. Victorious and grateful, the pasha of Mosul, Husayn Djalîlî “obtained a firman from Constantinople favourable to the churches of Mosul[9].” In 1744, the two Al-Tāhirā churches were built in Mosul, one for the Chaldeans, one for the Syriac-Catholics. The churches damaged by bombs were also restored.

The 17th century marked the opening of the Latin missions to Iraqi Mesopotamia. The Capuchin Friars open their first house in Mosul in 1636. The Dominicans of the Province of Rome arrived in 1750, followed by those from the Province of France in 1859. Under their impulsion, the large Latin church Our Lady of the Hour, was built “in the Byzantine style, between 1866 and 1873.” [10]This is the church to which the empress Eugénie de Montijot, wife of Napoleon III, donated the famous clock which was placed in the first clock tower ever built in Iraq. For almost three centuries, members of the Dominican mission for Mesopotamia, Kurdistan and Armenia, have been actors, experts and vital witnesses to the history of Christianity in Iraq and the dangers facing Christians in the Middle-East.

A turning point came in 1915-1918 with the genocide of the Armenians, Assyrians and Chaldeans in the Ottoman Empire. Large numbers of survivors came to live in Iraqi Mesopotamia, specifically in Mosul where there were pre-existing Christian communities. During this period, in January 1916 over the course of just two nights, 15,000 Armenian deportees living in Mosul and the surrounding area were exterminated, tied together in groups of ten and thrown into the Tigris river. Already, well before this carnage, on 10th June 1915, the German consul to Mosul, Holstein, telegraphed his Ambassador, reporting telling scenes: “614 Armenians (men, women and children) expulsed from Diarbekyr and transported to Mosul, were all killed en route, as they were transported by raft (on the Tigris). The kelekarrived empty yesterday. For a few days now the river has been carrying corpses and human limbs (…)” [11]

The fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003 and the rise of Islamic fundamentalism and associated criminal activity, had a considerable impact on the demographic collapse of Christian communities in Iraq, particularly in Mosul. On 1st August 2004, simultaneous attacks against five churches in Mosul and Baghdad triggered the mass exodus of the Christians of Mosul to protected areas in the Nineveh plain, Iraqi Kurdistan and overseas. The next few years in Mosul were truly harrowing. The targeted kidnapping and murders of Christians exacerbated the exodus. On 6th January 2008, Epiphany, and 9th January, criminal attacks targeted several Christian buildings in Mosul and Kirkuk.

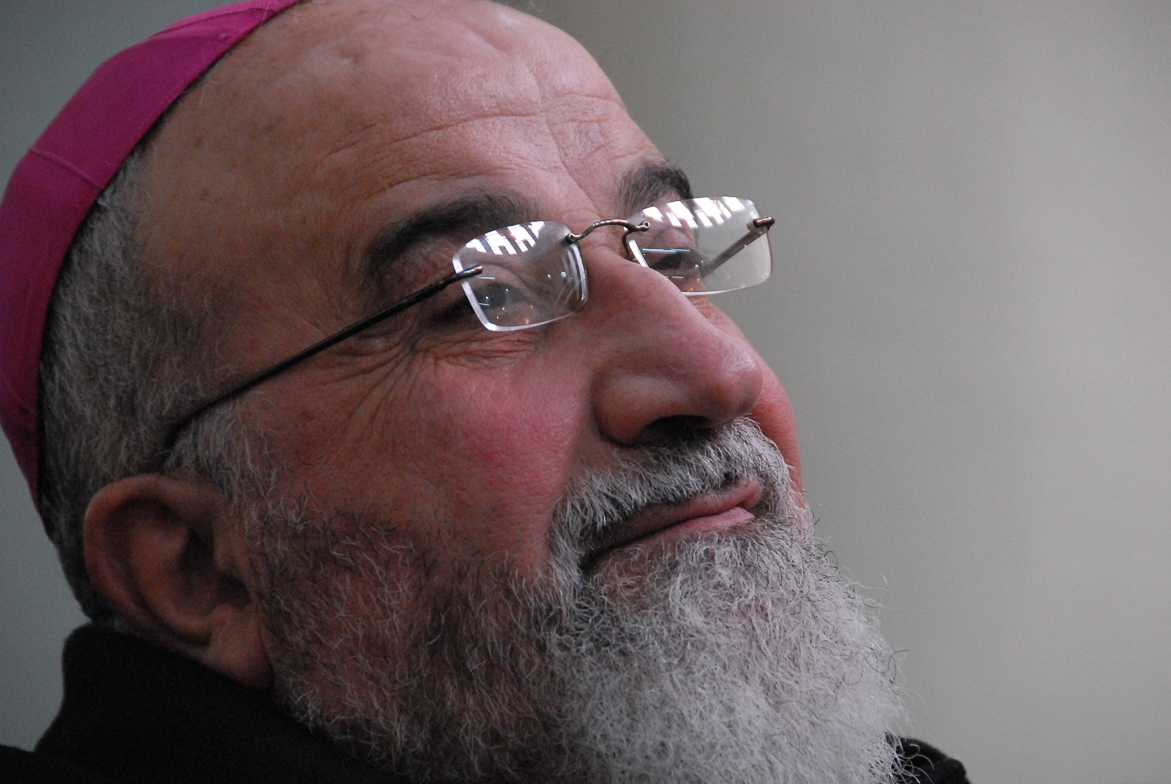

It was in this climate of terror that Monsignor Paulos Faraj Rahho, the Chaldean archbishop of Mosul was kidnapped. “On 13th February 2008, as he welcomed a delegation from Pax Christi, in the church in Karemlash, right next to Mosul, the prelate revealed that he had been threatened by a terrorist group several days previously, “Your life or five hundred thousand dollars,” the terrorists told him. “My life is not worth that!” he replied. One month later, on 13th March, Monsignor Rahho was found dead at the entrance to the city.”[12]

From June 2014 to July 2017, Mosul fell into the hands of ISIS fighters. The houses of the 10,000 or so Christians still living in the city were marked with the sign Nazrani(Nazarean, i.e. disciples of Jesus). They were ordered to convert to Islam, pay thedjizia(the tax on dhimmi) or die. They fled the city hastily anden massebut had to abandon their Christian heritage which was extensively looted, vandalised and desecrated. The battle of Mosul and the bombing by the international coalition which pulverised the ISIS fighters in a deluge of fire, reduced some of Mosul’s largest Christian (and Muslim) buildings to dust.

_______

[1]In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien »,Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Éditions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p.88

[2]In « Assyrie Chrétienne », vol.II, Jean-Maurice Fiey. Beyrouth, 1965. P. 115-116. See also “Mossoul chrétienne” by Jean-Maurice Fiey.

[3]In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 89

[4]In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien »,Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 92-93

[5]In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien »,Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 94

[6]In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien »,Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 95

[7]In « Vie et mort des chrétiens d’Orient », Jean-Pierre Valogne, Fayard, March 1994, p.740

[8]In « Histoire de l’Église de l’Orient »,Raymond Le Coz, Cerf, September 1995, p. 328

[9]In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien »,Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 97

[10]In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien »,Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 102

[11]In « L’extermination des déportés arméniens ottomans dans les camps de concentration de Syrie-Mésopotamie ». N° spécial de la Revue d’Histoire Arménienne Contemporaine, Tome II, 1998. Raymond H.Kevorkian. p.15

[12]In « Chrétiens d’Orient : ombres et lumières »,by Pascal Maguesyan, Éditions Thaddée, September 2013, latest edition 2014, p. 260

History of the Al-Tāhirā Chaldean Church in Mosul

The site of the construction of the Al-Tāhirā church in the 18th century can no doubt be explained by the prior existence of a “pilgrimage site, around the chapel of the church dedicated to the Virgin Mary, a church we found out about in a manuscript dated 1693 which gave its name to the Tāhirā church”[1]

A poem was“composed by CAbdal-ĞammalC Hassan Abd al-Bāqīin the time of Hussayn Pacha Ğalili,celebrating this victory. It is still sung today, especially in the month of May dedicated to the Virgin Mary, a song composed of 13 couplets celebrating “The Miracle”: “The Virgin Mary broke the Persians and the soldiers of Tāmas Hāntrembled before Her.”[2]

_______

[1]In « Les chrétiens de Mossoul et leurs églises pendant la période ottomane de 1516 à 1815», Fr.Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p. Mossoul-Ninive, 1983, p.104

[2]In « Les chrétiens de Mossoul et leurs églises pendant la période ottomane de 1516 à 1815», Fr.Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p. Mossoul-Ninive, 1983, p.104

Description of the Al-Tāhirā Chaldean Church in Mosul

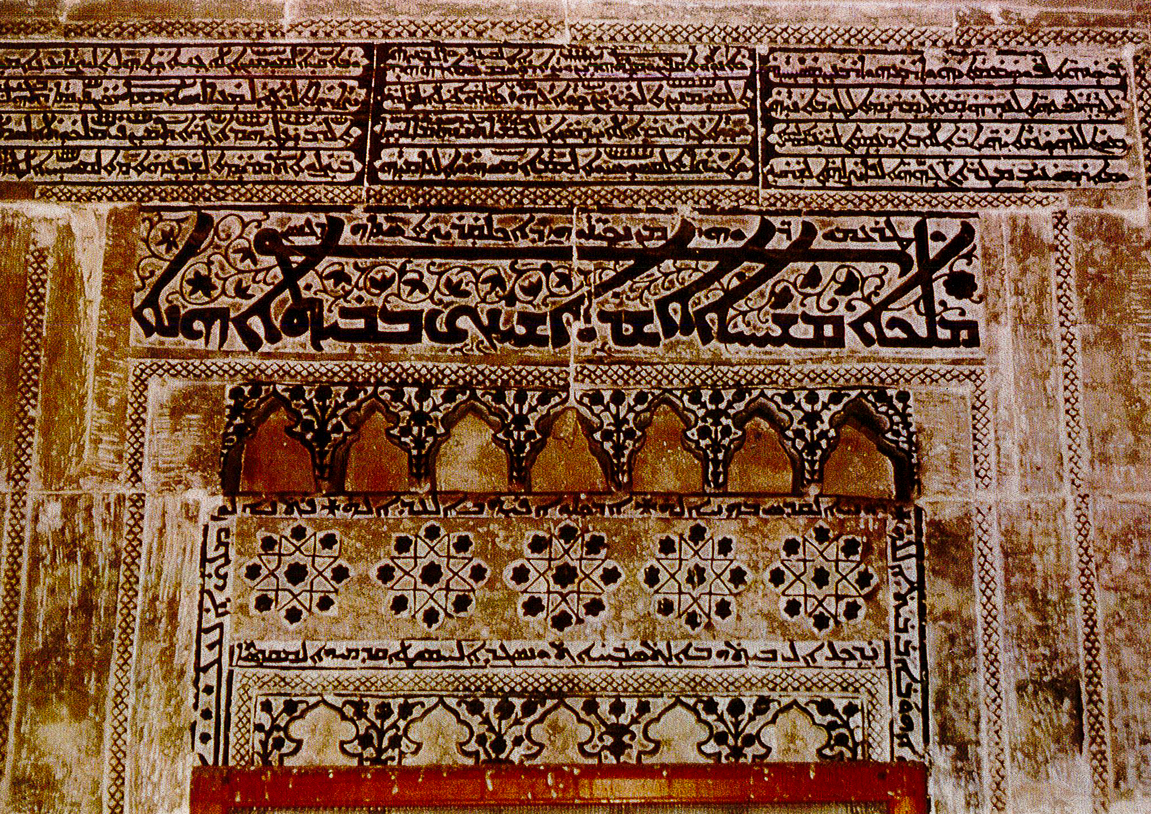

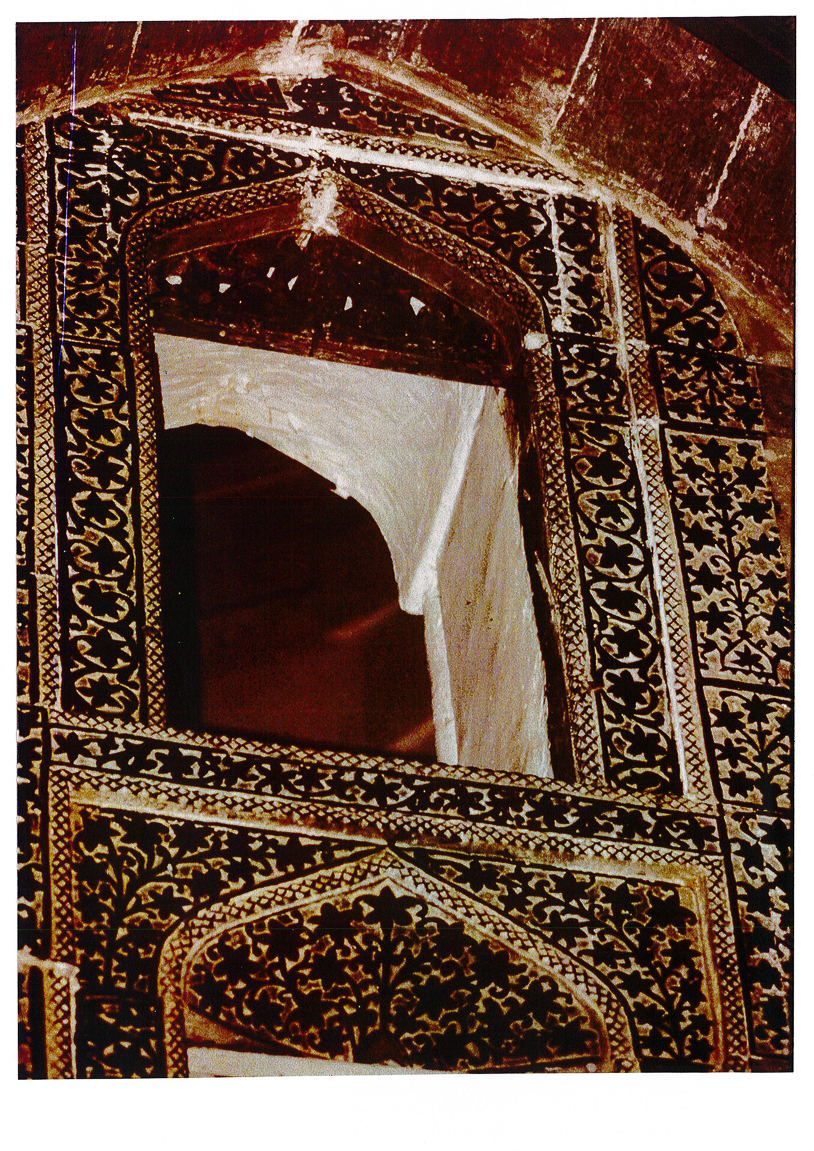

The Al-Tāhirā church is laid out around an open, interior courtyard, a space used for liturgy, which the other parts of the building radiate out from. On the day of our visit,[1]19th April 2018, this courtyard was still full of rubble caused by bombing. Under the northern gallery of the courtyard, the men’s and women’s doors are still clearly visible, magnificently decorated and enhanced with Syriac inscriptions, which appear to still be intact. To the east of this courtyard is the bētslōta(an oratory for prayer under the arches) and iwān(prayer niche). The baptistery can also be accessed from the extreme north-east end of the courtyard, next to the men’s door or from the inside of the church on the eastern side.

The church itself is entered after passing the two doors of the northern gallery. Inside, pre-war visitors were [2]“immediately struck by the imposing sculpted stone wall which separates the sanctuary from the nave.The wall is aligned with the royal door. This door is mounted with two lancet arches, covered in geometric designs and Syriac inscriptions; on the right-hand side, the door which opens onto the baptistery and on the left-hand side is firstly the door to the sacristy and then the door to the Martyrium. Several niches or “houses of martyrs” are also found on this wall. The royal door is composed of a curtain and magnificent, particularly ancient, wooden door and opens onto the sanctuary which contains an altar mounted with a stone rood screen. At the back of the church are the remains of the bema, with beautiful pieces of sculpted marble. In the centre of the nave, four pillars support elegantly-shaped vaults covered in discreet but graceful sculpted patterns.”[3]

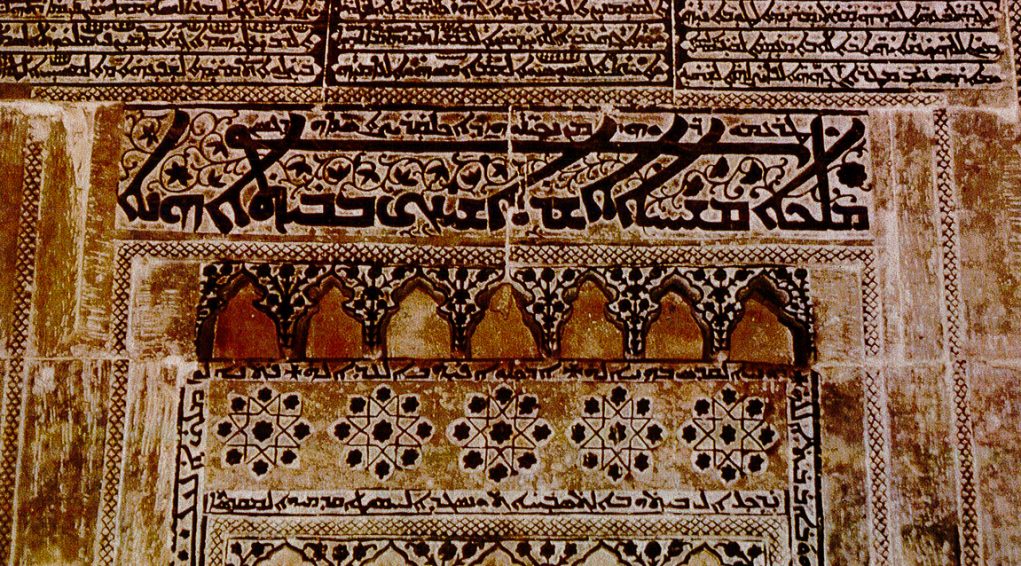

The Chaldean Al-Tāhirā church has a wealth of inscriptions which have been translated and interpreted.[4]They can be observed on the men’s and women’s doors, on the royal door and rood screen, as well as the iwanof the bētslōta(the oratory prayer niche). They constitute essential sources of historical information. “In the year 1744 of the Christian era, the church of the Holy Virgin Mary was renovated with the help of God and thanks to the care of the Father of Fathers, builder of churches, Mār’ Īliyā and Mar ĪšōCyāb, bishop of the venerable region of the East.”[5]We can also make out the names of benefactors, dedications, words of praise and affirmations, “in you, we will vanquish our enemies,”[6]as well as prayers of adoration and thanksgiving “Lord in your mercy, bless your church and grace the Temple consecrated to your glory, making it the most pure altar where we consecrate your most holy body and blood; o most holy fathers purify your thoughts from the stain of sin.” [7]

_______

[1]Delegation from the charity Mesopotamia and the Fondation Saint Irénée.

[3]In « Les chrétiens de Mossoul et leurs églises pendant la période ottomane de 1516 à 1815», Fr.Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p. Mossoul-Ninive, 1983, p.134

[4]The inscriptions were translated into French by Fr. Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p., in « Les chrétiens de Mossoul et leurs églises pendant la période ottomane de 1516 à 1815 », Mossoul, Ninive, 1983. Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p. Mossoul-Ninive, 1983, p.135-137.

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute