The Chaldean Sham’ûn Al-Safâ church in Mosul

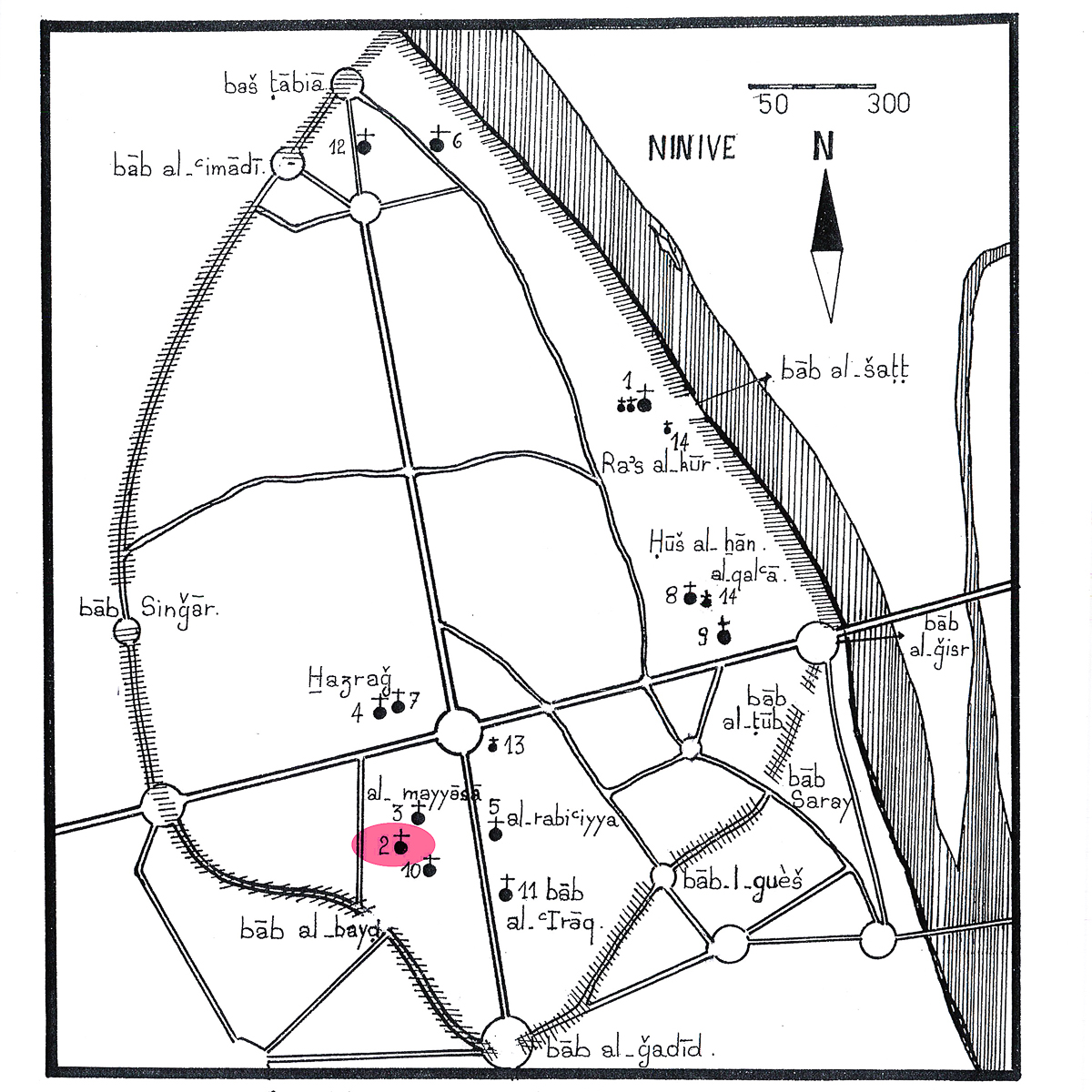

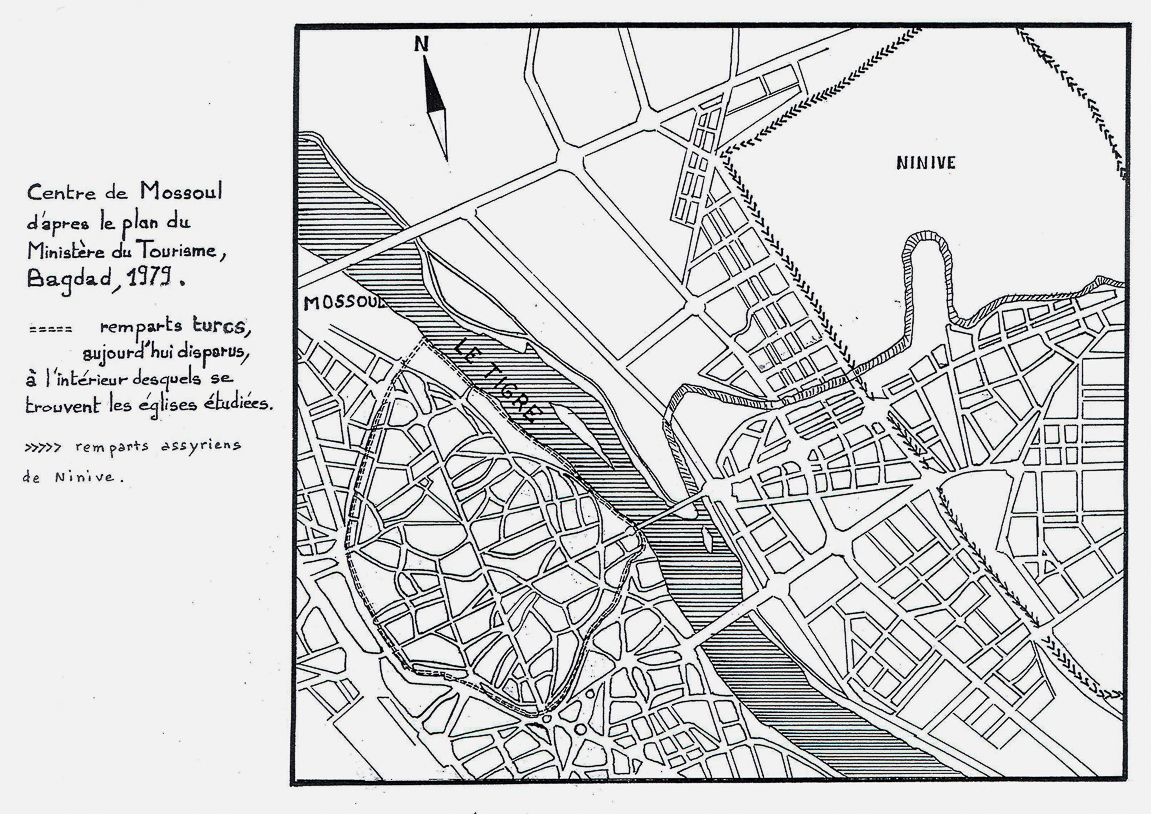

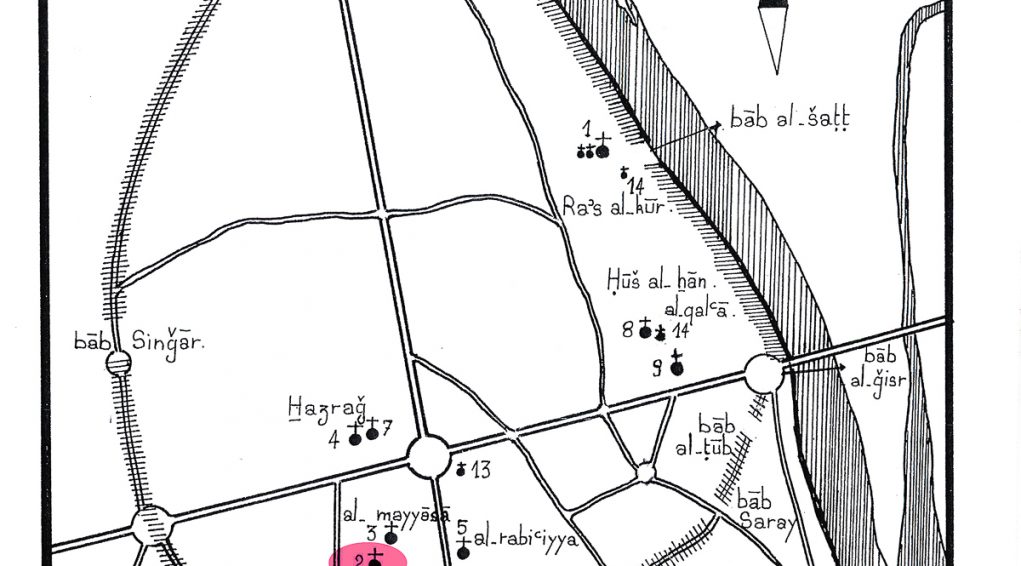

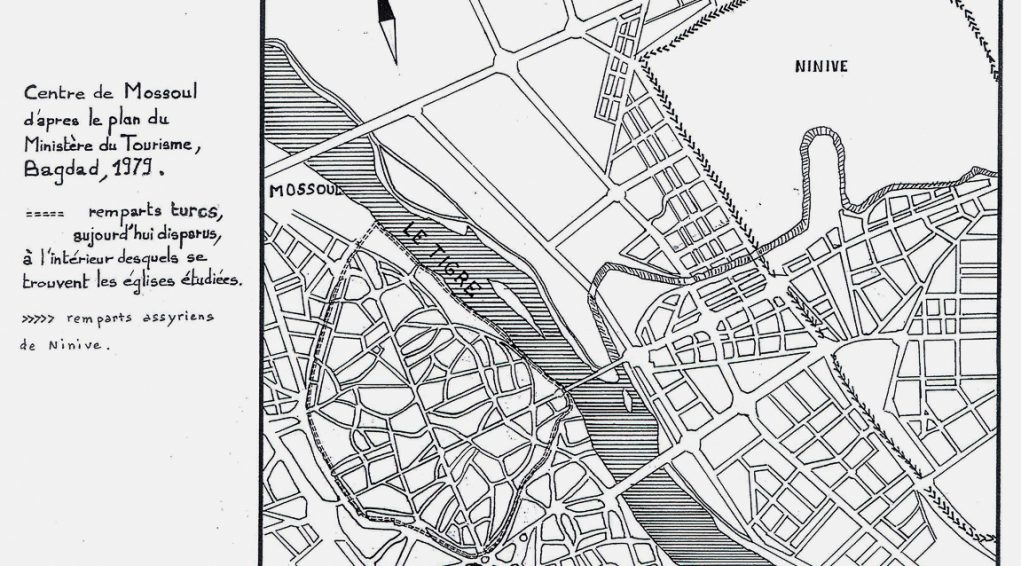

The Chaldean Sham’ûn al-Safâ church is located at 36°20’16.86″N 43°07’33.58″E (adjust) and 233 metres altitude, in the south-west of old Mosul, formerly designated by the Ottoman city walls, in the eponymous district also called al-Mayyāsā (or al-Mansūriyya) in Arabic.

Before it fell into ruins, the Sham’ûn al-Safâ church was described by numerous experts and travellers in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries.

The Sham’ûn al-Safâ church is dedicated to Simon Peter, Prince of the Apostles. We know very little about its foundation, but it would appear to be very ancient. Specialists tend to agree that it must have been founded around the 9th century.

Property of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East (Nestorian) up until the 18th century, the Sham’ûn al-Safâ church then became the property of the Chaldean church and became the episcopal seat.

The building is 27 metres long and 7 metres wide in the central section, it has a double, asymmetric nave.

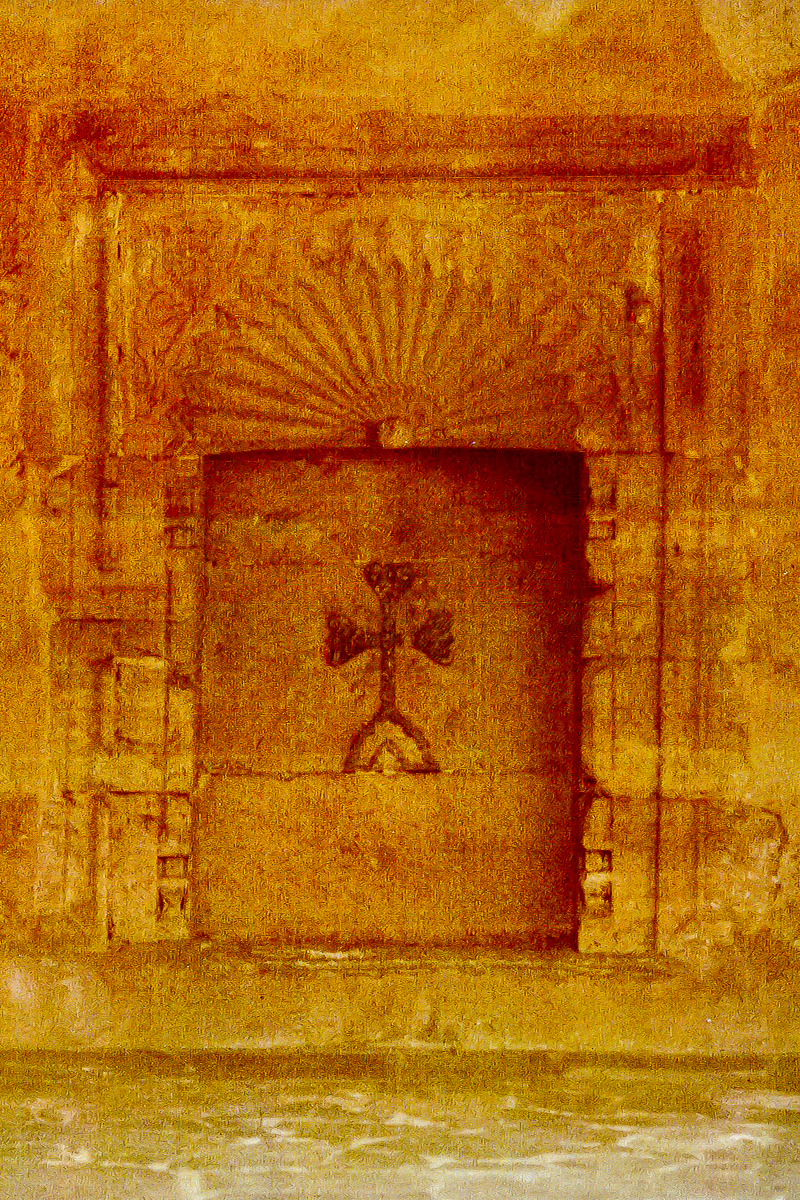

Pic : Entrance to the Shamoun al Safa church in 1975 © In “Monuments chrétiens de Mossoul et de la plaine de Ninive”, Slideshow, 2018, Slide 46, Fr. Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p.

Location

The Chaldean Sham’ûn al-Safâ[1] church is located at 36°20’16.86″N 43°07’33.58″E (check) and 233 metres altitude, in the south-west of old Mosul, formerly designated by the Ottoman city walls, in the eponymous district also called al-Mayyāsā (or al-Mansūriyya) in Arabic, 400 kilometres north of Baghdad. It is close to the ancient cathedral (Nestorian, then Chaldean) Meskinta. It also adjoins the ancient Chaldean seminary.

_______

[1] [1] Sham’ûn al-Safâ is also spelled: Šamcūn al-Safa. This is a transliteration from the Syriac, proposed by Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p.

The origins of the Chaldean church

The Chaldean Church is a Catholic church, born in the 16th century, further to a schism that occurred within the Church of the East. In 1552, several bishops, who had set up in northern Iraq[1], southern Turkey and northern Iran, contested the hereditary succession of the Catholicos of the Church of the East Shimun VIII. They elected in Mosul another Patriarch, Yohannan Sulaqa, abbot of Rabban Hormizd Monastery in Alqosh, who named himself Yohannan/John VIII and went to Rome to profess his Catholic faith. On 20th April 1553, Pope Julius III appointed him Patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic church “whose creation was thus officialised.[2]”

Back in the Ottoman Empire, he set up his patriarchate in Diyarbakır (southeast of modern days Turkey), 400 kilometres northwest from the monastery of Rabban Hormizd. Fighting openly with his rival Shimun VIII, Yohannan Sulaqa was arrested, imprisoned and murdered in 1555.

The foundation of the Catholic Chaldean Church had been preceded a century earlier, in 1445, by a decree of union in Cyprus between Rome and some members of the Church of the East, that Pope Eugene IV already called “Chaldeans”.

Up until the 19th century, this schism was all the more conflictual as a large number of worshippers from the Church of the East chose to remain in communion with Rome. The Catholic Chaldean Church’s see was transferred from Diyarbakır to Mosul in 1830, before the Metropolitan Yohannan VIII Hormizd was elected as Patriarch.

Though they undisputedly counted as the majority among the estimated 1 200 000 Christians in Iraq before the first Gulf war in 1991, the Chaldeans number 750 000 in the last census in 1987, compared to 300 000 Assyrians (Church of the East and former Church of East). The total number of Christian people in Iraq amounted then to 8% of the total population. How many were there in 2018? The data collected by Mesopotamia’s correspondents confirms the demographic collapse reported by the communities visited. There are less than 400,000 Chaldeans in Iraq, living in Baghdad, Kurdistan, the Nineveh plain and Basra. The disasters faced by the Christian communities in Iraq have not ceased since its independence in 1933. There was no respite at the start of the 21st century with the American invasion in 2003 and the terrible sanctions imposed by the UN, along with the violence and persecution perpetrated by Islamicist and organised crime groups, targeting Christian communities since the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime.

Today, the Chaldean church is composed of a large diaspora spread across five continents: the United States, Europe, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the former USSR, in particular in Russia (Moscow, Rostov-on-Don), Ukraine, Georgia (Tbilissi), Armenia (Yerevan).

_______

[1] [1]In the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire and Persia.

[2] In “Histoire de l’Église de l’Orient”, Raymond le Coz, Éditions du Cerf, 1995, p. 328

Fragments of the Christian history of Mosul

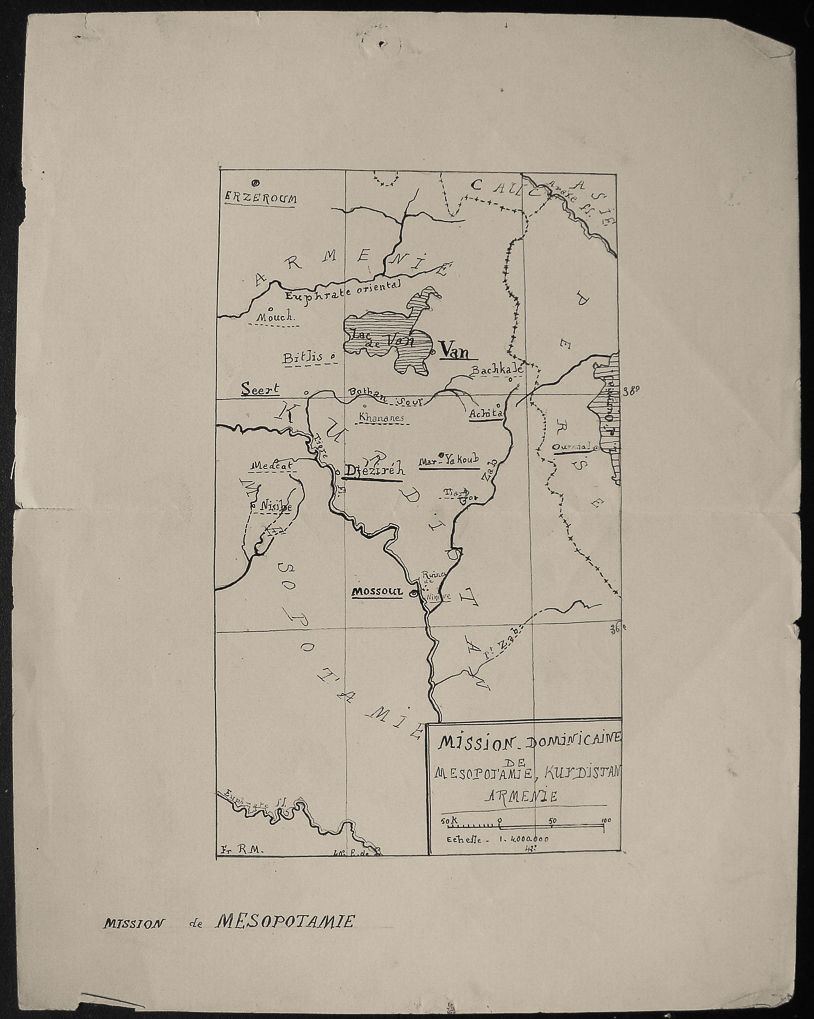

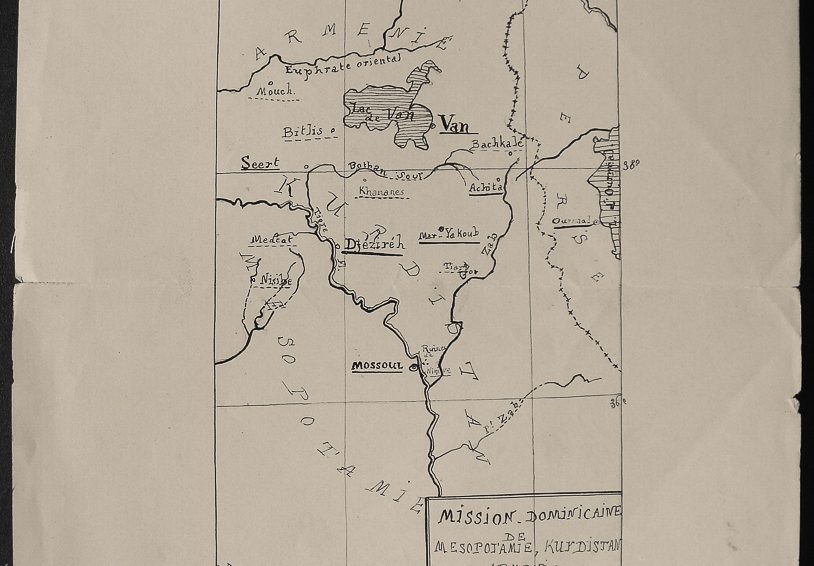

This chapter is largely based on the work of Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux [1] o.p. who lived in Iraq for 14 years from 1968 to 1983 as part of the Dominican mission for Mesopotamia, Kurdistan and Armenia, based in Mosul. See, two books by Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux, in particular: « Va à Ninive ! Un dialogue avec l’Irak », Éditions du Cerf, October 2000; and « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Éditions La Thune, Marseille, July 2015.

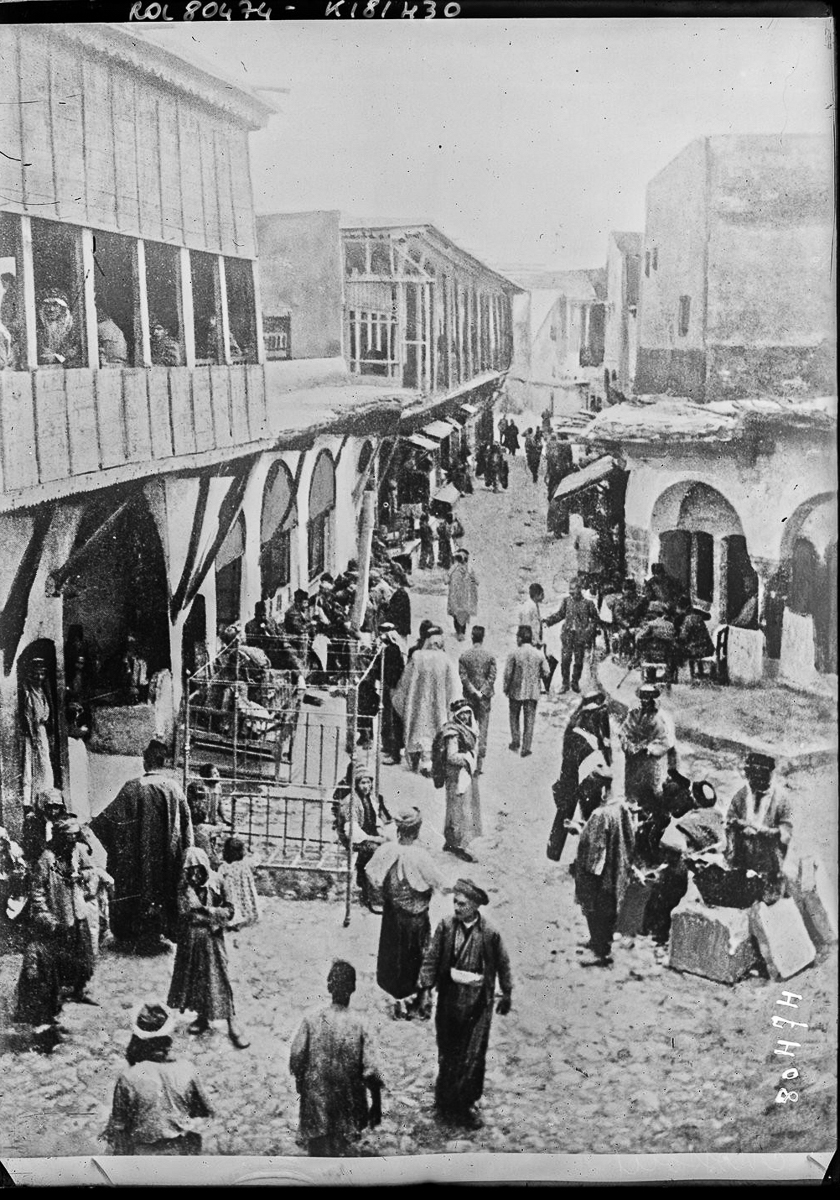

Mosul “remains a Christian metropolis [1]” as attested by its history, and its ancient and modern heritage, which persists despite recent catastrophic events.

Although the first archdiocese is attested to in 554[2], it is also important to take into account the Paleo-Christian apostolic tradition. “Three churches are proud to be founded on houses where apostles are said to have stayed. The Sham’ûn al-Safa’ church, [built during the Atabeg period in the 12th – 13th centuries] is said to be built where Saint Peter stayed during his visit to Babylonia and the Mar Theodoros church is connected to the visit of the apostle Bartholomew. As for the apostle Saint Thomas, the house where he was shown hospitality on his journey to India, became a church.[3]” The church in question is the Syriac-Orthodox church Mar Touma.

The first church attested to in Nineveh (modern-day Mosul-East) dates back to the year 570. It is mentioned in the “Chronicle of Seert”. It is the Isha’ya church. This confirms a pre-existing Christian community. In the 7th century the Syriac-Orthodox Mar Touma church was also known of. From the 7th century onwards, the Mar Gabriel monastery was the seat of one of the Church of the East’s most important schools of theology and liturgy. The al-Tāhirā Chaldean church was built on the site of this monastery in the 18th century.[4]

Over the centuries, through successive councils and conflicts, a multitude of churches of different denominations, including the Armenian and Latin churches, were formed.

Of these various fragments of history, the Muslim conquest must be cited as one of the most important. Mosul fell in 641 and the Christian members of its population became dhimmis, with (limited) rights and (stringent) obligations based on their religious identity. This status remained in force up until the 19th century and was abolished in the Ottoman Empire in 1855. Despite this abolition, Christians (and Jews) still remain defined by their dhimmi status which governs denominational relations in public life and attitudes in almost all Muslim countries. It is still legally enforced (in Iran).

In the 7th and 13th centuries, at the height of the Seljuq period, the Atabeg dynasties imposed their rule throughout Iraqi Mesopotamia and made Mosul a centre of power. At this time, Syriac-Orthodox Christians persecuted in Tikrit fled to the Nineveh plain and Mosul, where they established their community and founded the Mar Ahûdêmmêh (Hûdéni) church. “At the end of the 20th century due to below-ground flooding throughout the neighbourhood, the Mar Hûdéni church located well below ground level was flooded and had to be abandoned. A new church was built right on top of the old one. Thankfully, the royal door in the Atabeg style, described by Father Fiey as a “jewel of 13th century Christian sculpture”, was transported to the new church and given pride of place.” [5]

Following on from the Atabeg, the Mongol Houlagou Khan, took Mosul but spared the city from destruction and from the massacres committed in Baghdad in 1258, thanks to the “cunning governor of the city, Lû’lû, of Armenian origin.[6]” The following century was nonetheless a tragic one. “Christian persecutions peaked under Tamerlan, whose armies ravaged the Middle East in the first years of the 14th century and exterminated the Christian populations. No other eastern Christian church underwent anything close to this type of eradication, the community in Iraq is well placed to claim the first prize in martyrdom.”[7]

In 1516, Mosul fell into the hands of the Ottoman Turks for the first time, but it was not until the following century that they established a dominant presence in Iraqi Mesopotamia that was to last for four centuries after the conquest of Baghdad in 1638 by the sultan Murad IV.

In the 16th century Mosul was a major centre of Christian influence. It was here that the schism of the Church of the East took place, with the election of Yohannan Sulaqa as the first patriarch of the Chaldean church Abbot of Rabban Hormizd Monastery in Alqosh, he took on the name Yohannan/John VIII and went to Rome to profess his Catholic faith. On 20th April 1553, Pope Julius III appointed him Patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic church “whose creation was thus officialised.[8]” After Diyarbakır (in the south-east of modern-day Turkey) and before Baghdad (in 1950), the seat of the Chaldean church was established in Mosul in 1830, with the election of Jean VIII Hormez as the metropolitan of Mosul.

In 1743, the Christians of Mosul played an active role in defending the city during the 42-day siege laid by the Persian Nâdir Shâh who had already looted and ransacked the plain of Nineveh. Victorious and grateful, the pasha of Mosul, Husayn Djalîlî “obtained a firman from Constantinople favourable to the churches of Mosul[9]”. In 1744, the two al Tāhirā churches were built in Mosul, one for the Chaldeans, one for the Syriac-Catholics. The churches damaged by bombs were also restored.

The 17th century marked the opening of the Latin missions in Iraqi Mesopotamia. The Capuchin Friars open their first house in Mosul in 1636. The Dominicans of the Province of Rome arrived in 1750, followed by those from the Province of France in 1859. Under their impulsion, the large Latin church Our Lady of the Hour, was built “in the Byzantine style, between 1866 and 1873.[10]” This is the church to which the empress Eugénie de Montijot, wife of Napoleon III, donated the famous clock which was placed in the first clock tower ever built in Iraq. For almost three centuries, members of the Dominican mission for Mesopotamia, Kurdistan and Armenia, have been actors, experts and vital witnesses to the history of Christianity in Iraq and the dangers facing Christians in the Middle-East.

A turning point came in 1915-1918 with the genocide of the Armenians, Assyrians and Chaldeans in the Ottoman Empire. Large numbers of survivors came to live in Iraqi Mesopotamia, specifically in Mosul where there were pre-existing Christian communities. During this period, in January 1916 over just two nights, 15,000 Armenian deportees living in Mosul and the surrounding area were exterminated, tied together in groups of ten and thrown into the Tigris river. Already, well before this carnage, on 10th June 1915, the German consul to Mosul, Holstein, telegraphed his Ambassador, reporting telling scenes: “614 Armenians (men, women and children) expulsed from Diarbekyr and transported to Mosul, were all killed en route, as they were transported by raft (on the Tigris). The kelek arrived empty yesterday. For a few days now the river has been carrying corpses and human limbs (…)” [11]

The fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003 and the rise of Islamic fundamentalism and associated criminal activity, had a considerable impact on the demographic collapse of Christian communities in Iraq, particularly in Mosul. On 1st August 2004, simultaneous attacks against five churches in Mosul and Baghdad triggered the mass exodus of the Christians of Mosul to protected areas in the Nineveh plain, Iraqi Kurdistan and overseas. The next few years in Mosul were truly harrowing. The targeted kidnapping and murders of Christians exacerbated the exodus. On 6th January 2008, Epiphany, and 9th January, criminal attacks targeted several Christian buildings in Mosul and Kirkuk.

It was in this climate of terror that Monsignor Paulos Faraj Rahho, the Chaldean archbishop of Mosul was kidnapped. “On 13th February 2008, as he welcomed a delegation from Pax Christi, in the church in Karemlash, right next to Mosul, the prelate revealed that he had been threatened by a terrorist group several days previously, “Your life or five hundred thousand dollars,” the terrorists told him. “My life is not worth that!” he replied. One month later, on 13th March, Monsignor Rahho was found dead at the entrance to the city.”[12]

From June 2014 to July 2017, Mosul fell into the hands of ISIS fighters. The houses of the 10,000 or so Christians still living in the city were marked with the sign Nazrani (Nazarean, i.e. disciples of Jesus). They were ordered to convert to Islam, pay the djizia (the tax on dhimmi) or die. They fled the city hastily and en masse but had to abandon their Christian heritage which was extensively looted, vandalised and desecrated. The battle of Mosul and the bombing by the international coalition which pulverised the ISIS fighters in a deluge of fire, reduced some of Mosul’s largest Christian (and Muslim) buildings to dust.

_______

[1] In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Éditions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p.88

[2] In Assyrie chrétienne, vol.II, Jean-Maurice Fiey. Beirut, 1965. P. 115-116. See also “Mossoul chrétienne” by Jean-Maurice Fiey.

[3] In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 89

[4] In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 92-93

[5] In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 94

[6] In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 95

[7] In “Vie et mort des chrétiens d’Orient”, Jean-Pierre Valogne, published by Fayard, 1994, p.740

[8] In “Histoire de l’Église de l’Orient”, Raymond le Coz, Éditions du Cerf, 1995, p. 328

[9] In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 97

[10] In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 102

[11] In “L’extermination des déportés arméniens ottomans dans les camps de concentration de Syrie-Mésopotamie”. Special edition of Revue d’Histoire Arménienne Contemporaine, Tome II, 1998. Raymond H.Kevorkian. p.15

[12] In « Chrétiens d’Orient : ombres et lumières », by Pascal Maguesyan, Éditions Thaddée, September 2013, latest edition 2014, p. 260 260

History of the Chaldean Sham’ûn al-Safâ church in Mosul

Sources and citations in “Les chrétiens de Mossoul et leurs églises pendant la période ottomane de 1516 à 1815”, Fr. Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p. Mossoul-Ninive,1983, p. 100 to 103 A.

The Sham’ûn al-Safâ church is dedicated to Simon Peter, Prince of the Apostles.

Nothing very much is known about its foundation, although it would appear to be “clearly very ancient”. Specialists tend to agree that it must have been founded around the 9th century[1], with a 13th century baptistery[2]. A date closer to the period between the 4th and 7th centuries cannot be ruled out, however.[3]

The tomb of Father Ibrahim, who died in the 13th century in 1255 (or 65) is located in the martyrion (bēt sahdē). This date is the most ancient trace of the Sham’ûn al-Safâ church.

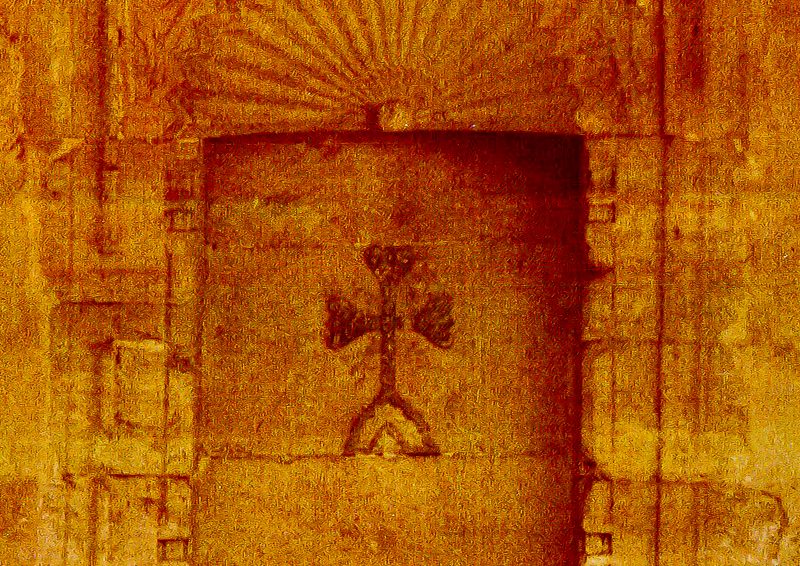

Another indication used to date the church is an inscription in Arabic dating back to the Atabeg period (12th – 13th centuries) on which several names are engraved, discovered on a wall of the gallery to the south side of the church.

An inscription around the men’s door dates from between the 13th and the 14th century. The inscription reads: “Here is the door of the Lord, where the Holy Spirit lies (…)”.[4]

Property of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East (Nestorian) up until the 18th century, the Sham’ûn al-Safâ church then became the property of the Chaldean church and became the episcopal seat.

The 1847 restoration is attested to in an inscription above the royal door: “You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church; in the year 1847 anno domini.”

The Chaldean archdiocese of Mosul has conserved several manuscripts from the 17th and 18th centuries in the name of the Sham’ûn al-Safâ church.

A sign of its importance, it was in Sham’ûn al-Safâ that the vault of a famous family of the Djalili dynasty, several members of which governed Mosul, was found. “In this vault, left to the Dominicans in the 18th century, a Capuchin brother was buried in 1724, followed by a Carmelite in 1757, according to P Lanza” and subsequently it was used for other Dominican monks.

At the beginning of the 1980s, the Sham’ûn al-Safâ church was classed by the Mosul city hall as a priority for restoration. Unfortunately, in the year 2000 the church was still in ruins[5]. The political chaos after 2003, and the war from 2014 – 2017 with its catastrophic consequences, did not contribute to a more favourable outlook.

_______

[1] Father Habbi and Father Haddad, quoted by Fr. Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p.

[2] According to the friar and scholar Jean-Maurice Fiey, quoted by Fr. Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p.

[3] In “Les églises et monastères du Kurdistan irakien à la veille et au lendemain de l’islam”, PhD thesis by Narmen Ali Amen, May 2001 Saint Quentin University in Yvelines, p.251.

[4] Quoted in full in “Les chrétiens de Mossoul et leurs églises pendant la période ottomane de 1516 à 1815”, Fr. Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p. Mossoul-Ninive,1983, p. 102.

[5] Visit by the archeologist Narmen Ali Muhamad Amen

Description of the Chaldean Sham’ûn al-Safâ church in Mosul

Sources and citations in “Les chrétiens de Mossoul et leurs églises pendant la période ottomane de 1516 à 1815”, Fr. Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p. Mossoul-Ninive,1983, p. 100 to 103 A.

Before it fell into ruin, the Sham’ûn al-Safâ church was described by several experts and travellers, including the British archaeologist Claudius James Rich in the 19th century and the German Ernst Herzfeld in the first half of the 20th century, as well as the French Dominicans Jean-Maurice Fiey and Jean-Marie Mérigoux in the 20th century and the Iraqi archaeologist Narmin Ali Amin at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries. The description below describes the church as it might have been seen at the beginning of the 1980s:

The Sham’ûn al-Safâ church is accessed via a discreet, simple door, to the west of the building, behind which is a “passage six metres above the church courtyard that is first seen from above.” A staircase descends into the courtyard, allowing the visitor access to the level of the church as it was in the 7th century, this is where the ancient tombs are found.

Around the courtyard, a gallery opens onto the church to the north and an open-air altar (bēt slōta) is found to the east aligned with the entrance, mainly used during the summer months.

Under the north gallery are two entrance doors to the church, one for men and one for women.

The building is 27 metres long and 7 metres wide in the central section, it has a double, asymmetric nave. The main nave, to the right, has a narthex at the westernmost end, via which the baptistery can be accessed. To the east, the royal door opens onto a sanctuary complete with a high altar with steps positioned against the wall of the apse, above which is a cupola. The left side aisle is slightly curved to the west. At the end of this side aisle is the sacristy (bēt diācōn) and a secondary altar. To the north of the side aisle, aligned with the entrance to the church is the alcove containing the martyrion (bēt sahdē).

The church also contains several niches containing relics, to the left of the royal door and in the side aisle.

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute