The Armenian Apostolic Church Surp Nerses Shnorhali in Dohuk-Nohadra

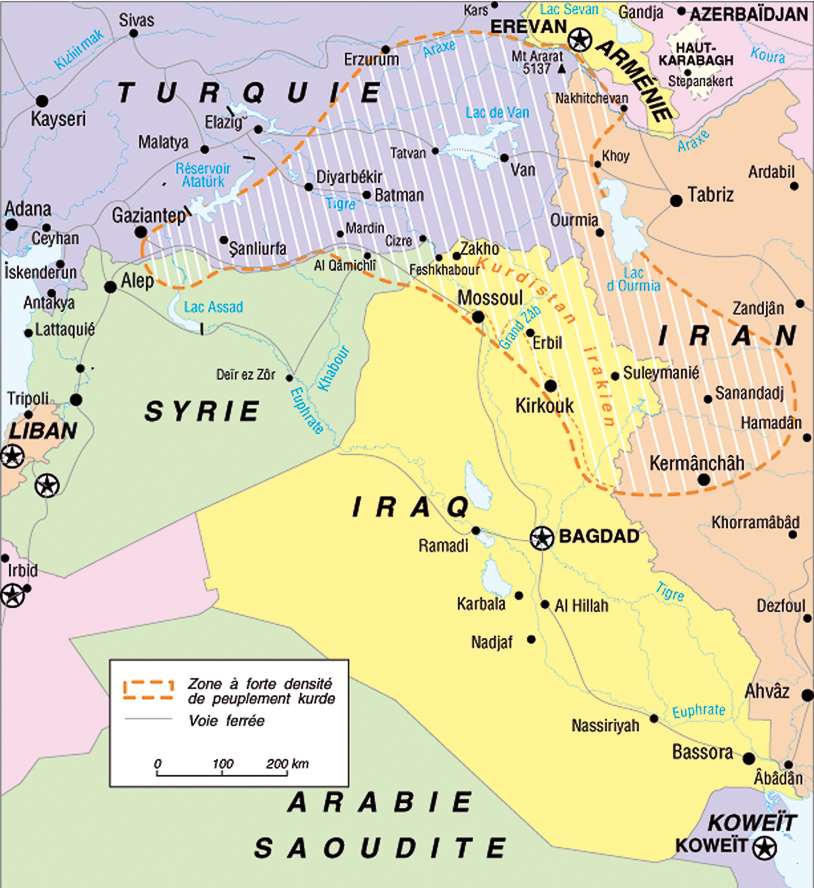

The Armenian Apostolic Church Surp Nerses Shnorhali (Saint Nerses the Gracious) is located at 36°51’30.0″N 43°00’00.0″E(coordinates for Dohuk)and at 1167 metres altitude, in Dohuk-Nohadra, capital of the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan.

In 2000, there were 43 Armenian families living in Dohuk-Nohadra. In 2016-2017, with the arrival of displaced families from the Nineveh plain and Mosul there were 93 families in the city. Prior to 2008, there was no Armenian church in Dohuk. The Armenian residents requested hospitality from the Assyrian Church to celebrate weddings, baptisms and funerals. They also attended the Armenian church in Zakho, 55 km to the north-east. The Armenian church Surp Nerses Shnorhali was built in 2008 and consecrated in 2009.

The Surp Nerses Shnorhali church is characteristic of Armenian sacred architecture. It is laid out in a free cross-shape (the arms of the cross are visible from the outside) monocoque (one single apse to the east) and longitudinal (the east-west axis of the cross is longer than the north-south axis).

Pic : The Armenian Sourp Nerses Shnorhali church in Dohuk-Nohadra. August 2017 © Pascal Maguesyan / MESOPOTAMIA

Location

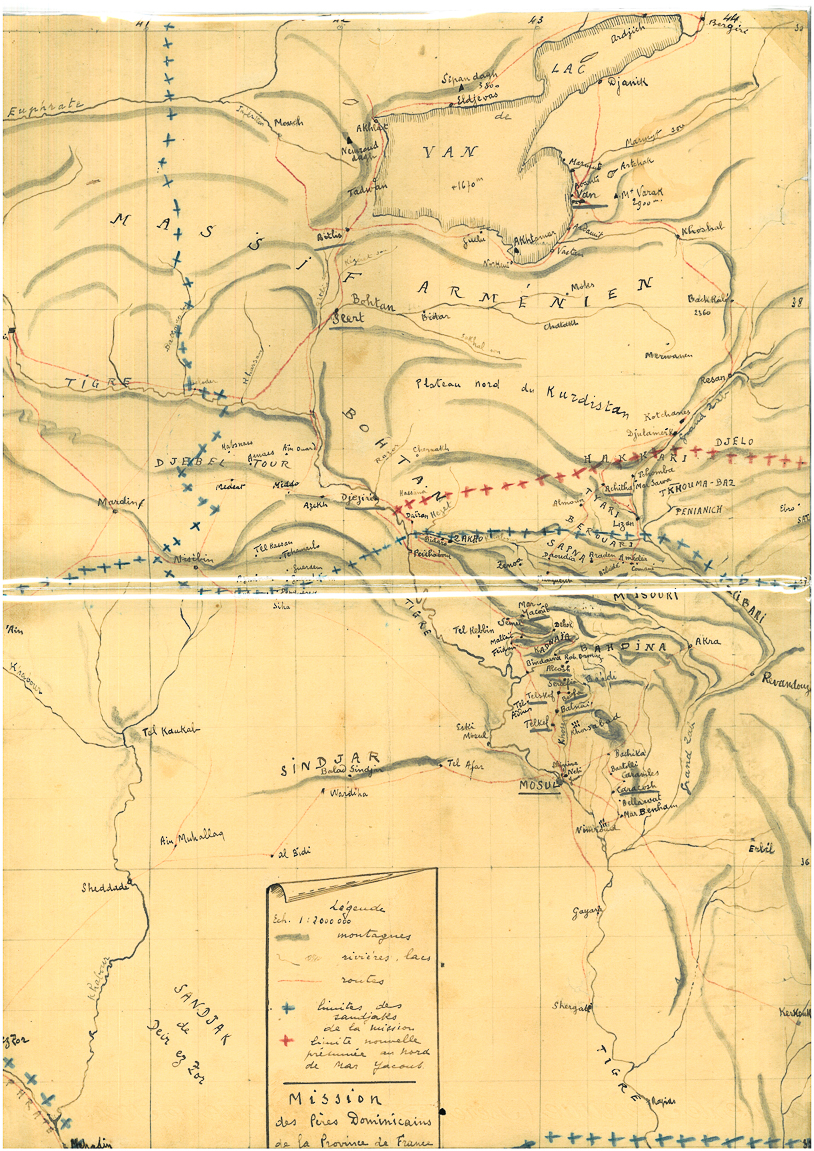

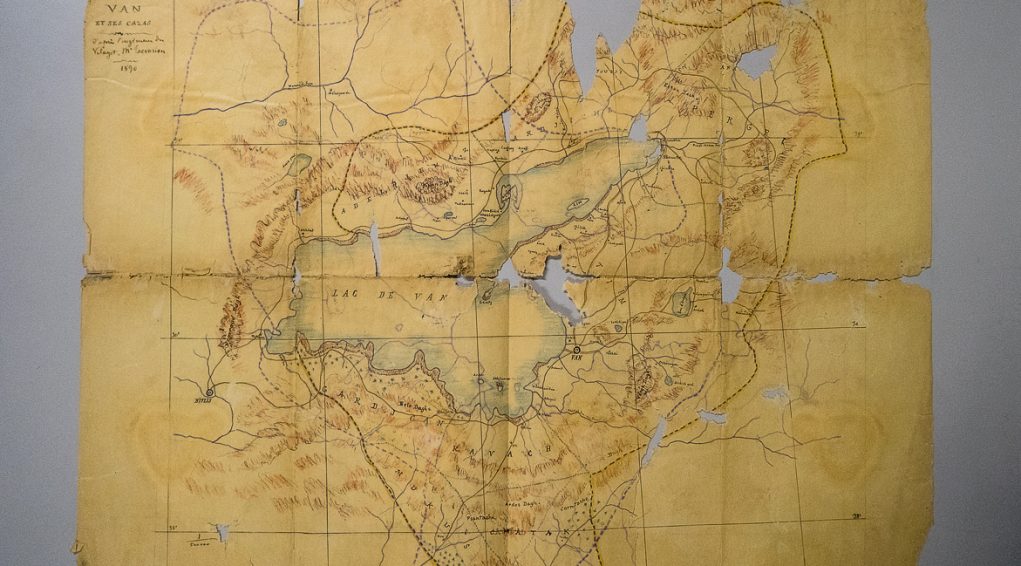

The Armenian Apostolic Church Surp Nerses Shnorhali (Saint Nerses the Gracious) is located at 36°51’30.0″N 43°00’00.0″E(coordinates for Dohuk) and 1167 metres altitude, in Dohuk-Nohadra, provincial capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, 70 km to the north of Mosul, 150 km north-west of Erbil and 60 km south-east of the Turkish/Syrian border.

Origins of the Armenian presence in Iraq

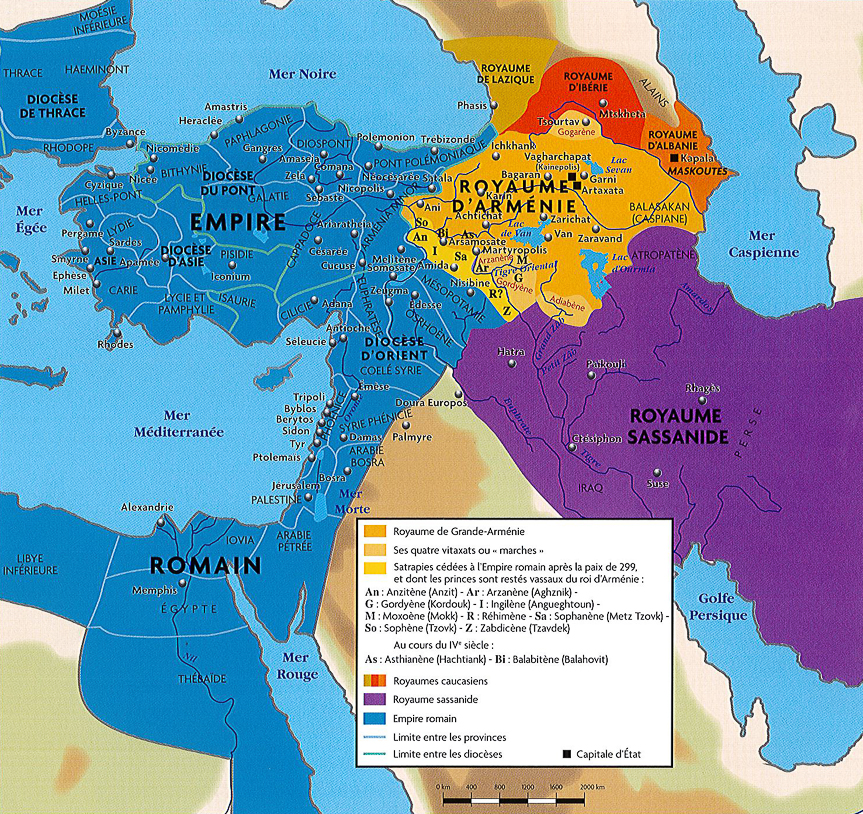

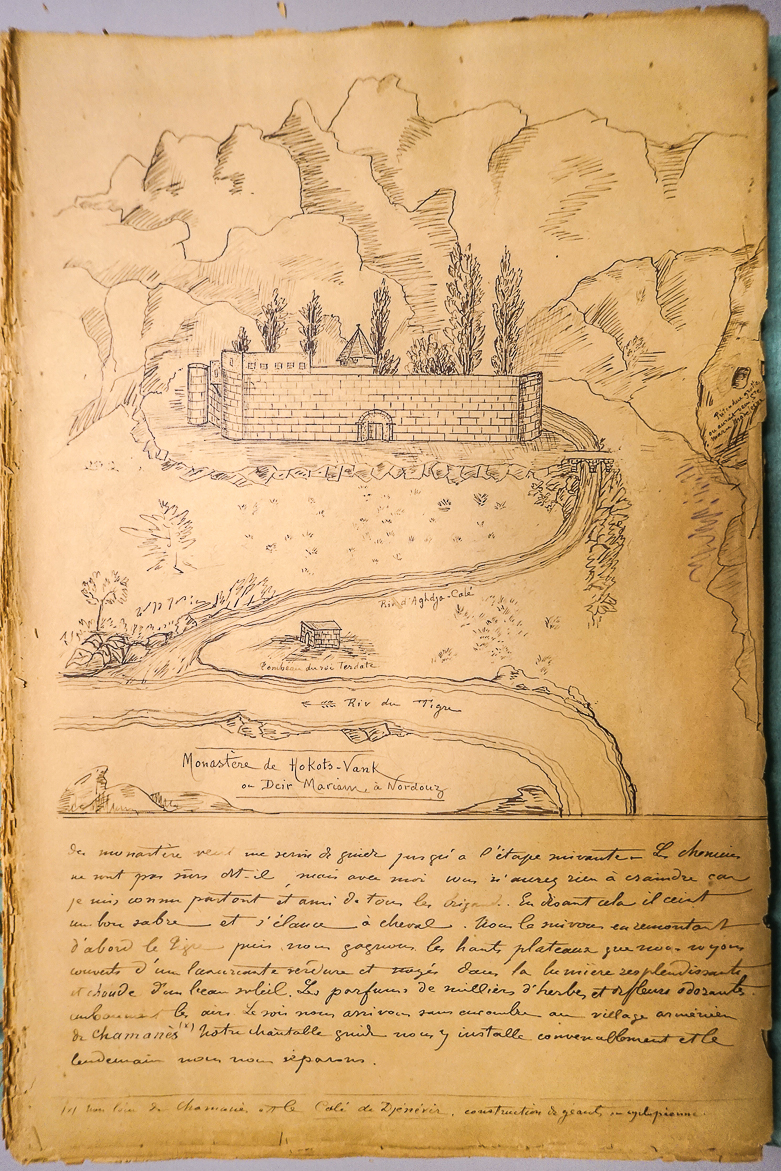

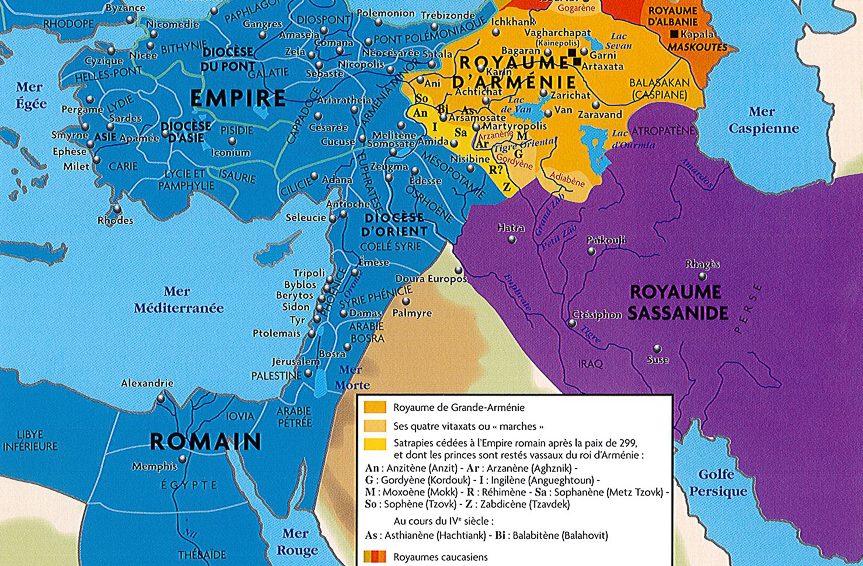

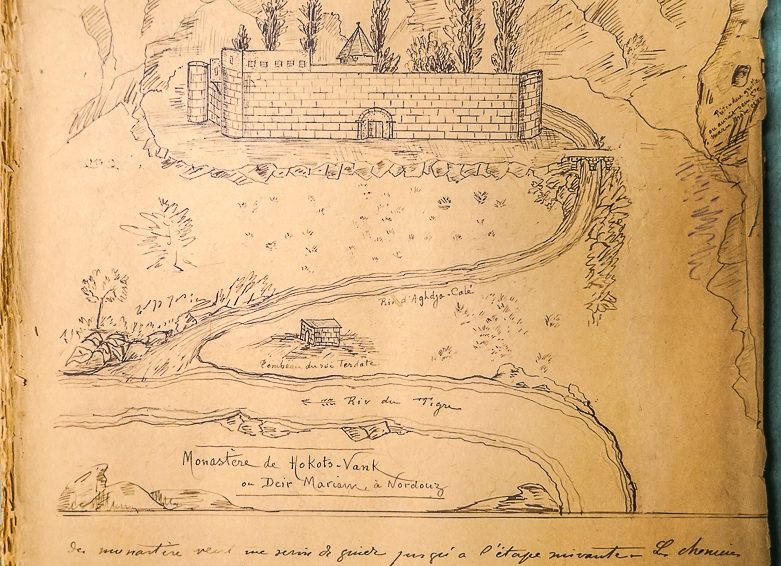

The origins of an Armenian presence in Mesopotamia have come along for centuries since Antiquity. In the 1st century BC, the Adiabene kingdom (with Arbeles/Erbil as “capital city”) was part of the Armenian Kingdom of Tigranes II the Great. At the very beginning of the 4th century, the area of Abadiene, which was then the most southern territory of the kingdom of Armenia, became the very first Christian “state” in History, around 301. “What also seems reliable is that there has been a meeting, around 328-329, between the only two Christian sovereigns in those times: the Roman emperor Constantine I and the Armenian Tiridates III. Constantine I confirmed the role of Tiridates III in the evangelisation of the East. In this way, the Armenian missionaries participated in the evangelisation of Mesopotamia and the Sassinid kingdom, as recounted by the Greek historian Sozomene, in around 402: “then amongst the neighbouring peoples, the belief progressed and grew in large numbers and I think that the Persians became Christians thanks to the relationships they had with the people of Osroene[1]and Armenia (…)”[2].”

In the 17th century, new Armenian communities settled in Iraqi Mesopotamia after the Persian Shah Abbas I conquered Baghdad in 1623. In the early years of the 17th century, the Persian king forced the Armenian population of Julfa (former Armenian city in the Nakhichevan, on the northern bank of the Aras river) into exile. Twelve thousand Armenian people were then moved to New Julfa (Nor Djougha), at the gates of Isfahan, to take part in the development of the Safavid-Persian Empire’s new capital city. After Shah Abas died, the Armenians from Persian endured times of troubles. Lots of them moved to Mesopotamia and settled in Basra (south of nowadays Iraq), whereas some others set off to India.

When the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV regained control over Baghdad in 1638 with the help of Armenian Ottoman soldiers and a new phase started for an Armenian settling in Baghdad. Throughout the period of Ottoman domination and until the fall of the Empire at the beginning of the 20th century, the Armenians developed their institutions so much that by the end of the 19th century they were nearly 90,000 living in Iraq.[3]

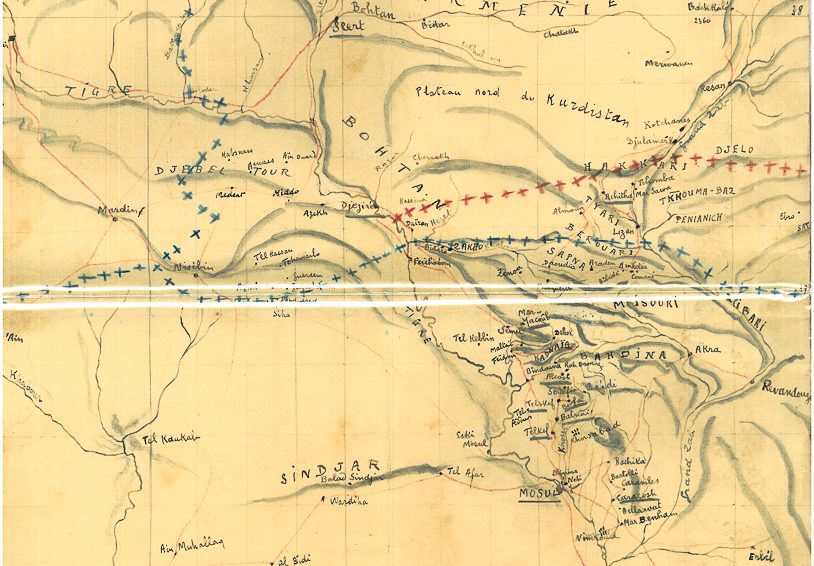

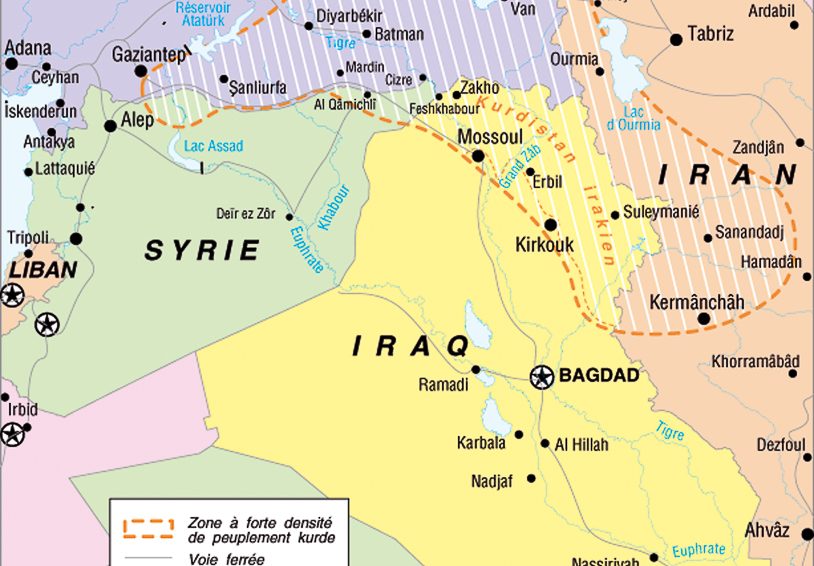

The genocide of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in 1915-17 was the last, terrible reason for their migration towards Iraqi Mesopotamia. Deported from the eastern provinces of the Empire, coming from the North (Diyarbekir) along the Tigris river, from the West (Ras-al-Ain) along the railway from Aleppo to Baghdad, or also from Van and then coming first through Persia, the Armenians arrived in some relegation areas such as Zakho, Avrest, Avzruk but also Kirkurk and Mosul. At this time a particularly tragic incident took place. In January 1916 over just two nights, 15,000 Armenian deportees living in Mosul and the surrounding area were exterminated, tied together in groups of ten and thrown into the Tigris river. Already, well before this carnage, on 10th June 1915, the German consul to Mosul, Holstein, telegraphed his Ambassador, reporting telling scenes:“614 Armenians (men, women and children) expulsed from Diarbekyr and transported to Mosul, were all killed en route, as they were transported by raft (on the Tigris). The kelekarrived empty yesterday. For a few days now the river has been carrying corpses and human limbs (…)” [4]

Nowadays, the Armenians in Iraq mostly descend from people who survived the 1915 genocide. Rather discreet on the political scene, they are known for being loyal and developing their own educational, social and religious infrastructure.

From a religious point of view, the Armenians from Iraq are mostly members of the Armenian Apostolic Church (autocephalous church since its origin in 301), some are members of the Catholic community[5]and some others joined a small evangelic community.

After Saddam Hussein’s regime fell in 2003, the situation worsened considerably. The attacks from Islamic and Mafia groups against Iraqi Christians also targeted the Armenians and their churches. On August 1st 2004, the Armenian Catholic church Our Lady of the Rosary, in Baghdad, Karada district, was struck by a bomb attack. An Armenian church under construction was also targeted on December 4th 2004. For nearly 20 years, these successive spates of violence set the tempo for Iraqi Armenians’ mass exodus. The battle of Mosul over the summer 2017 and the bombing intensity also affected the Armenian heritage. Before 2003, there were probably more than 25,000 Armenians in Iraq, whereas today the community leaders assert there are 10,000 to 13,000 Armenians still living in Iraq. Half of them are said to be living in Baghdad. The remainder live in Iraqi Kurdistan, Kirkuk, Sulaymaniyah, as well as Basra. There are no more Armenians in Mosul.

_______

[1]The people of Osroene were the inhabitants of Edessa. Edessa was a major capital city in ancient times, before becoming a powerhouse of Christianity during its infancy. Armenian tradition recounts that the King of Edessa and Armenia, Abgar V, wanted to welcome Christ to his Kingdom and issued an invitation. It was not Christ who came to Edessa but one of his apostles Thaddeus (Jude). Edessa was renamed Urfa and remained the capital of the principality. This city has been known as Şanlıurfa since 1984 (in Turkey).

[2]In “Arménie, un atlas historique”, p.22 and map p.23. Publisher Sources d’Arménie, 2017.

[3]Source: Armenian Embassy in Iraq

[4]In « L’extermination des déportés arméniens ottomans dans les camps de concentration de Syrie-Mésopotamie ». Special edition of the review, Histoire Arménienne Contemporaine, Tome II, 1998. Raymond H.Kevorkian. p.15

[5]The website of the Armenian Embassy in Iraq reads as follows:“In 1914, there were 300 Armenian Catholics in Iraq. After the First World War and up until 2003, the community reached a total of 3,000 members. Nowadays, there are 200 – 250 Armenian Catholic families in Iraq. The Armenian Catholics have two churches: Our Lady of Flowers built in 1844, and the Sacred Heart of Christ built in 1937. In 1997, the main Armenian Catholic church was restored and is considered to be the largest church in Baghdad. The archbishop Emmanuel Dabaghian is the Primate of the Armenian Catholics in Iraq.”

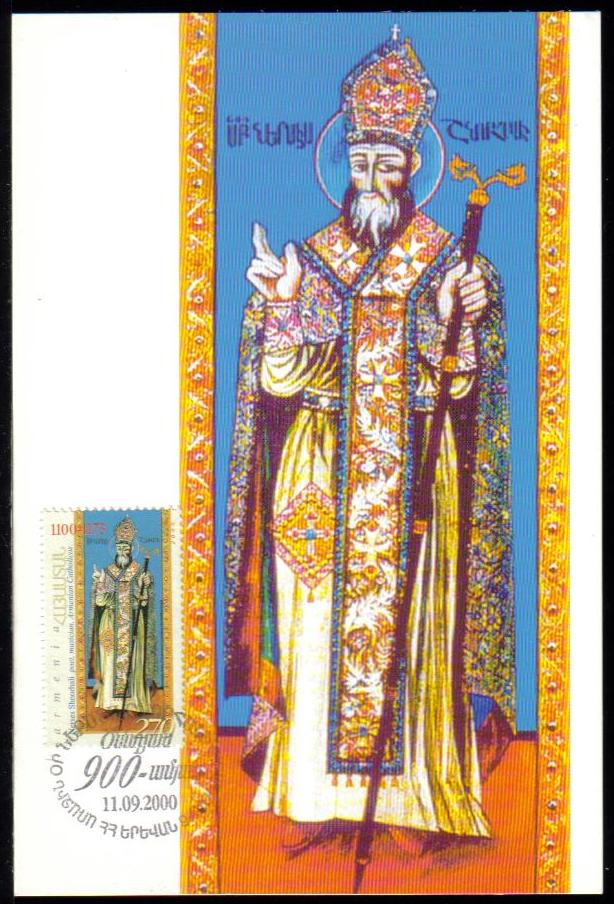

Who was Surp Nerses Shnorhali (Saint Nerses the Gracious)?

Born in 1102, into the noble Pahlavuni family, Nerses Glaietsi was elected Catholicos(supreme, universal leader) of the Armenian Apostolic Church. In the office of the Armenian Catholicos, he was known as Nerses IV up until his death in 1173. The Armenian name Shnorhali meansGracious or Full of grace.It was given to him due to his spiritual, literary and intellectual influence. A renowned theologian, he professed faith in “Christ Man-God, against the Monophysitism (of Eutyches), favouring his divine nature and Nestorianism, favouring his human nature.[1]” He developed links with the Greek Byzantine Catholic Church, for both oecumenical and, no doubt, political reasons. A poet, he wrote numerous canticles as well as prayers for every hour of the day. One of these “I confess with faith” is composed of 24 remarkable verses[2]. The first reads: “I confess with faith and worship you, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, uncreated and immortal Essence, creator of angels, humans and of all that exists.Have mercy upon your creatures.”

_______

[1]In « Les Arméniens, histoire d’une Chrétienté », Gérard Dédéyan, Éditions Privat, p. 37

History of the Armenian Apostolic Church Surp Nerses Shnorhali (Saint Nerses the Gracious)

In 2000, there were 43 Armenian families living in Dohuk-Nohadra. In 2016-2017, with the arrival of displaced families from the Nineveh plain and Mosul there were 93 families in the city. Prior to 2008, there was no Armenian church in Dohuk. The Armenian residents requested hospitality from the Assyrian Church to celebrate weddings, baptisms and funerals. They also attended the Armenian church in Zakho, 55 km to the north-east.

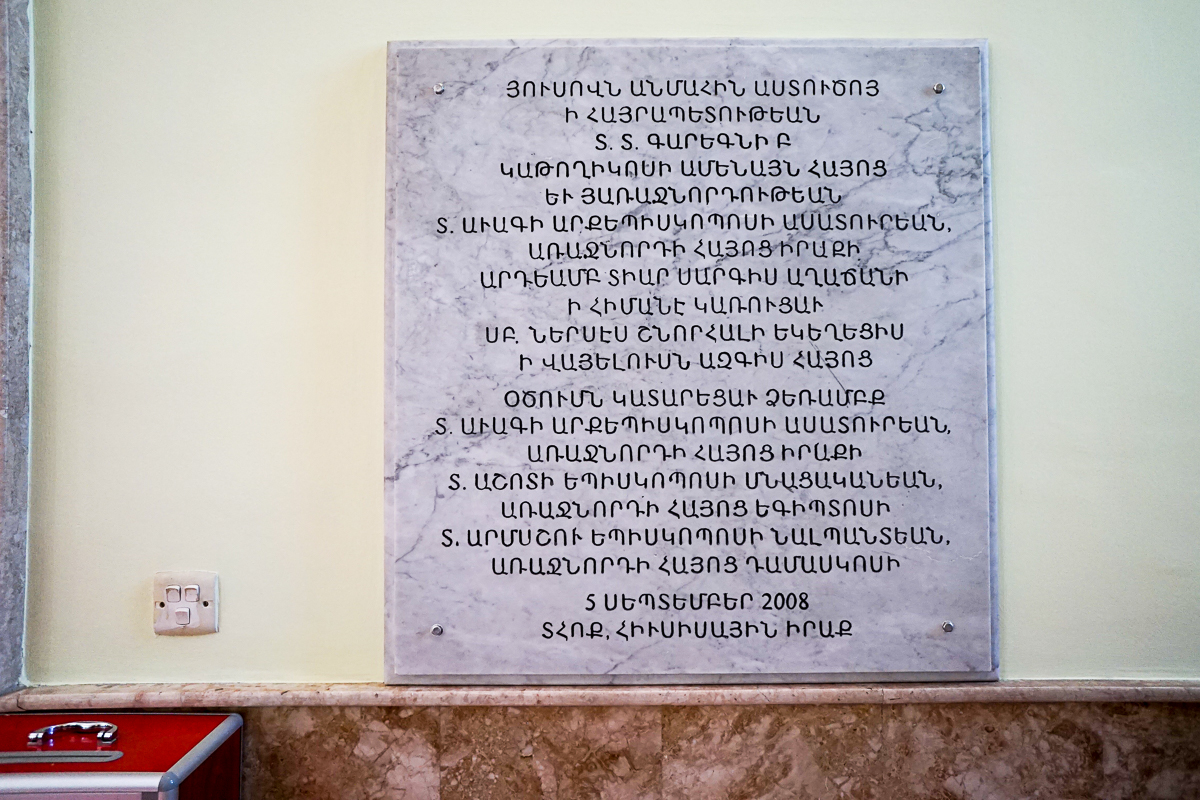

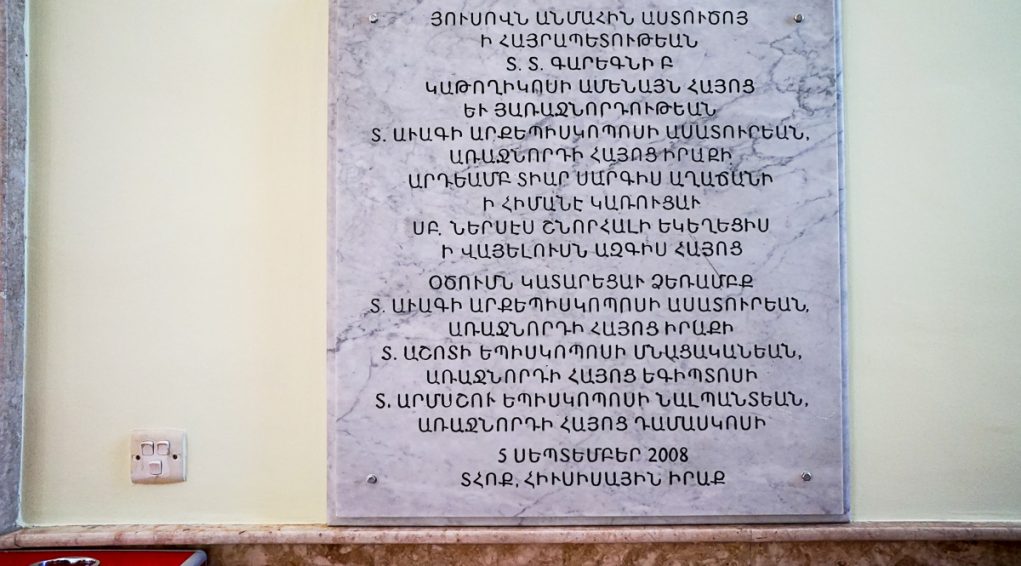

The Surp Nerses Shnorhali church was built in 2008 (a plaque inside the church engraved in Armenian dated 5 September 2008 attests to this) and consecrated in 2009. It is the work of the architect Yervant Aminian, an Armenian member of the Iraqi Kurdistan parliament[1]. The construction of this church was funded by the government of the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan, via the intermediary Sarkis Aghajan, Iraqi Christian benefactor and former Minister of the Economy and Finances.

Father Massis Chahinian, archpriest of the Armenian Apostolic Surp Nerses Shnorhali church in Dohuk-Nohadra[2], regrets that the Armenians of Iraq were isolated during the exodus of Christians from the Nineveh plain. They have no relations with the Armenian diaspora or with the Republic of Armenia. “Not one single Armenian came to visit us!”

_______

Description of the Armenian Apostolic Church Surp Nerses Shnorhali (Saint Nerses the Gracious)

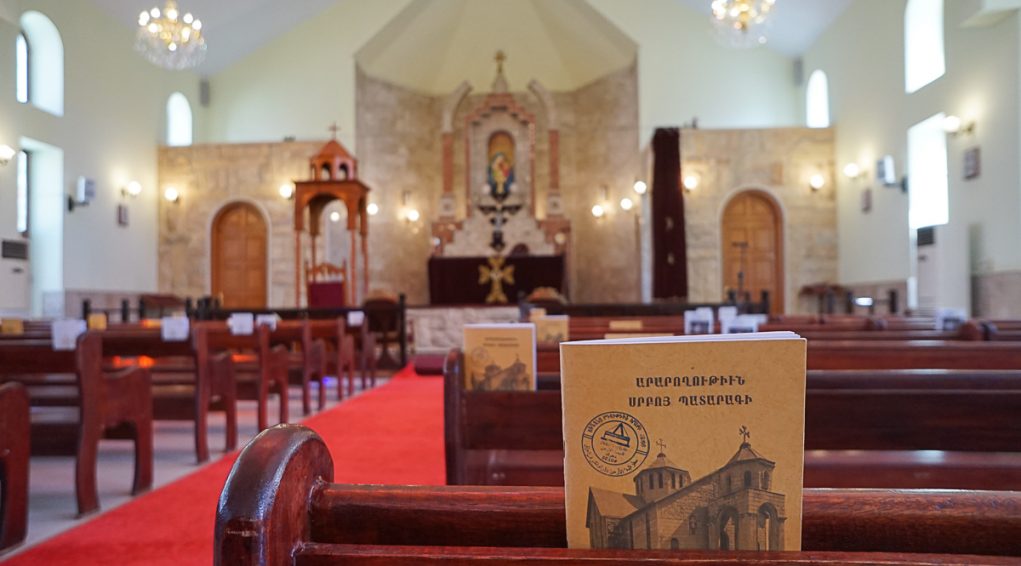

The Armenian church Surp Nerses Shnorhali is a building made of reinforced concrete, covered with ochre and beige facing stones on the outside and painted inside.

The church is characteristic of Armenian sacred architecture. It is laid out in a free cruciform (the arms of the cross are visible from the outside) monocoque (one single apse to the east) and longitudinal (the east-west axis of the cross is longer than the north-south axis). Its octagonal cupola is formed from a drum with windows and a pyramid roof mounted with a metal Armenian cross.

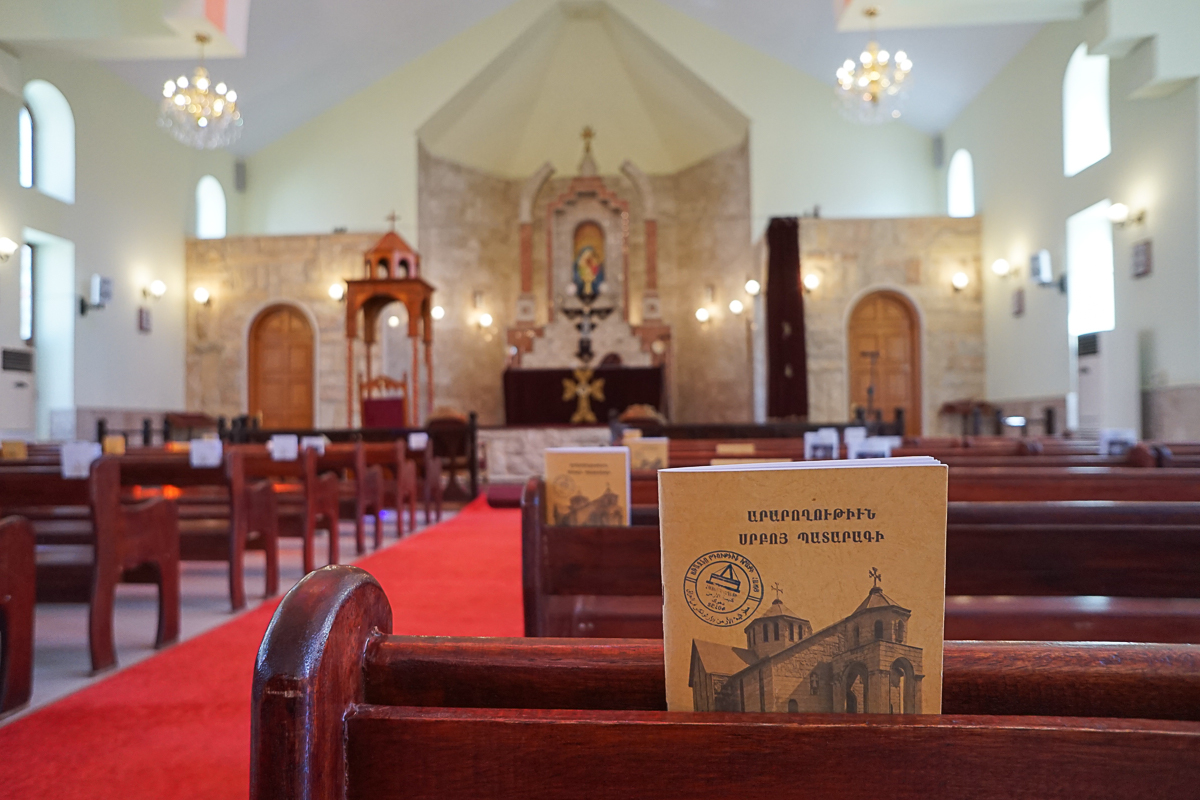

The entrance to the building to the west, is preceded with a two-level bell tower porch with rotunda. The wooden entrance door is adorned with a sculpture of an Armenian flowered cross. After passing through the entrance, above the western arm of the cross is a tribune for the choir.

The church is well lit with natural light from the numerous stained-glass windows on the north and south facades and from the drum.

A wooden choir screen separates the nave from the sanctuary. This is composed of two parts. The lower part can be accessed by worshippers during the Eucharistic communion or the celebration of sacraments. The upper part, the bem, is a platform on which stands the high altar with steps leading up to it. In the form of an arch, covered with two-colour marble plaques, it is decorated with the Virgin of Tenderness, whose large blue veil covers the infant Christ holding onto his mother with his right arm around her shoulder. Behind the high altar is a narrow ambulatory, which separates it from the apse wall.

In the church courtyard is a large khatckar (finely sculpted Armenian stone cross) erected in 2015, to commemorate the centenary of the Armenian genocide.

Against the wall of the church there is a small prayer altar before which pilgrims burn votive candles in front of a statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

A three-storey building was built on the religious estate on which the Armenian Surp Nerses Shnorhali church stands. It contains offices, a community centre, a Sunday school and accommodation (for families in need and newly-married couples).

A second community centre was built to meet the growing needs of the Armenian community.

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute