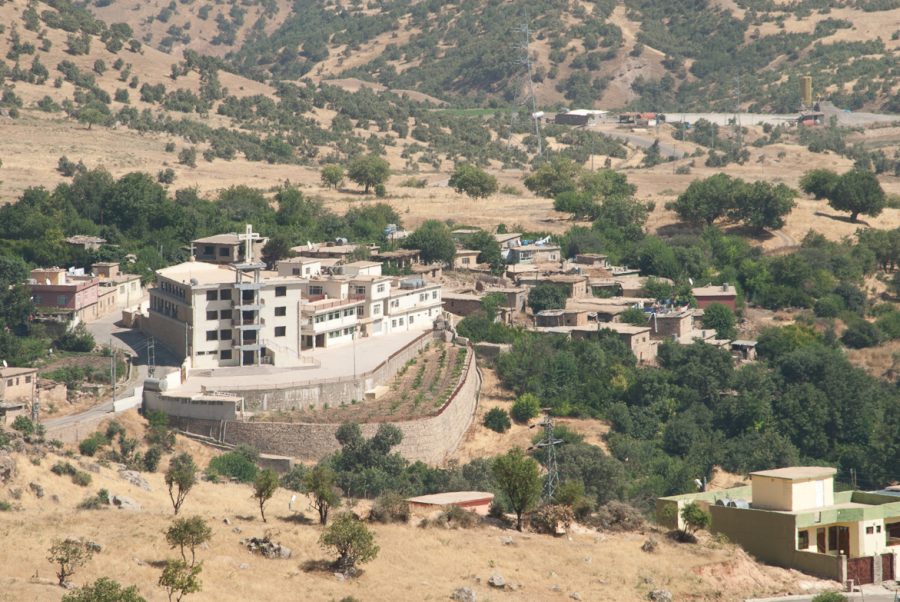

The former Chaldean archdiocese in Amadiya

The former archdiocese in Amadiya is located at 37°5’37.50″N 43°29’9.30″E and at 1163 metres altitude, in the north-west of the city.

Amadiya was one of the most dynamic Chaldean dioceses in Iraq. Its large library attests to its influence. Unfortunately, it came to a dramatic end, looted and burned to the ground shortly after the Kurdish uprising in 1961.

Despite its undeniable charm, Amadiya progressively lost its cultural, religious and community vitality.

The former archdiocese appears abandoned. The charmless building, masks below it, at ground level, a small single nave church with a pointed barrel vault. Two rows of wooden benches and a high altar complete with liturgical furniture attest to the continuity of worship.

Photo : The internal courtyard of the former archdiocese in Amadiya. July 2017 © Pascal Maguesyan / MESOPOTAMIA

Location

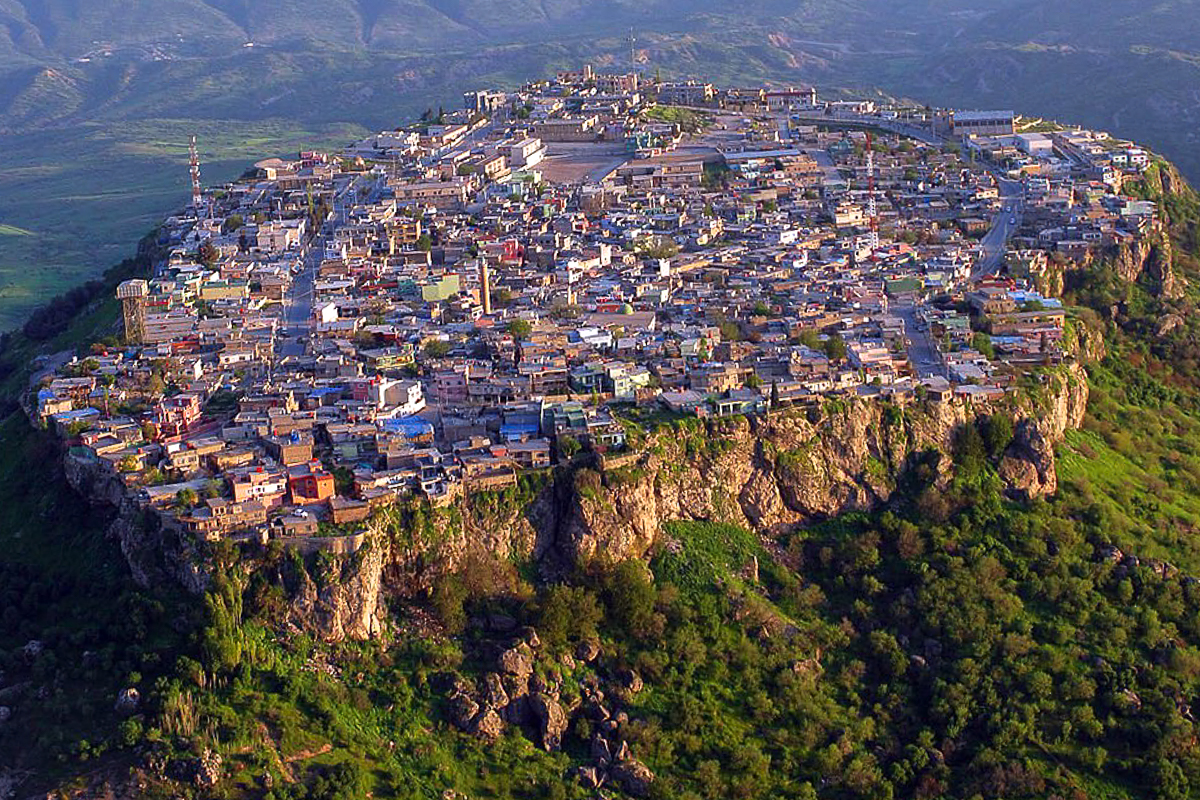

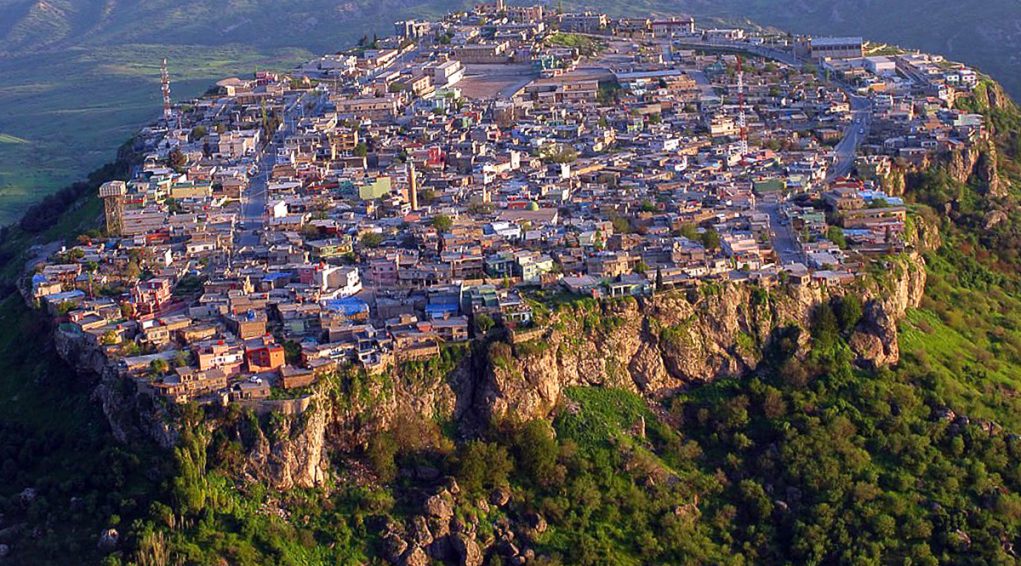

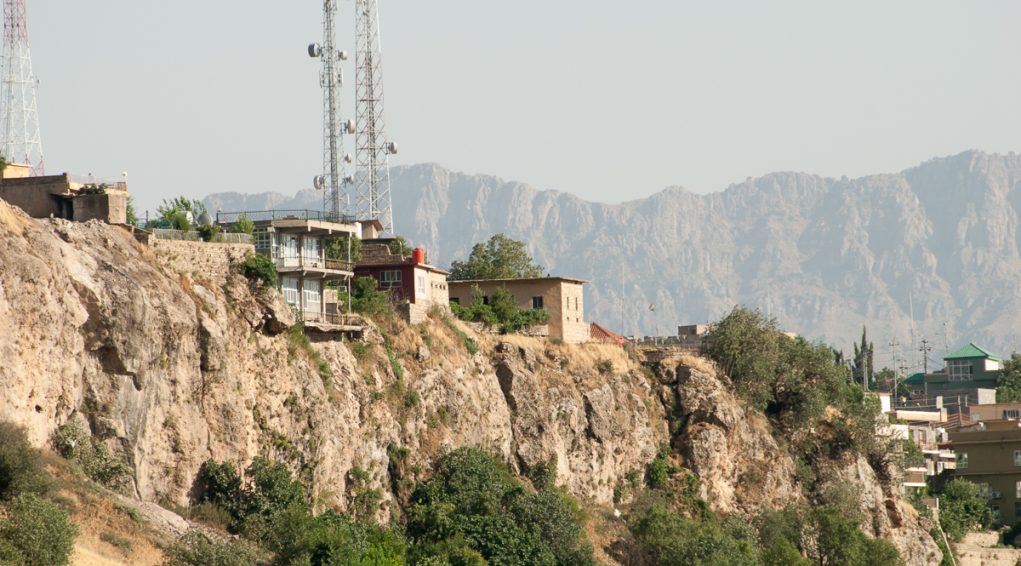

The former archdiocese in Amadiya is located at 37°5’37.50″N 43°29’9.30″E and at 1,163 metres altitude, in the north-west of the city. Built on a rocky plateau overlooking valleys and ravines, Amadiya is an impressive natural citadel with majestic panoramic views. Amadiya is also a popular Iraqi holiday destination, in particular in the summer months.

Amadiya is 17 kilometres south of the Turkish border and 90 kilometres east of Dohuk-Nohadra.

Fragments of Christian history

The Christian history of Araden is very similar to that of other villages of the area with a pre-existing Jewish presence and early evangelization under the influence of apostles Thomas, Addai (can also be the apostle Jude, also known as Thaddeus in the Gospel) and Mari. Throughout a 4thcentury full of vocations, the tradition relates many stories of martyrs persecuted by the Persian king Shapur II. And all along these times of the first Christians, hermitages and primitive sanctuaries developed, at the very same place where Assyrian churches and monasteries were progressively raised. Throughout the centuries and until the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the valleys and the mountains which surround this part of Mesopotamia were a place of flourishment and protection for the Church of the East, on both sides of the modern-day Iraq-Turkey border, where Catholic missions flourished as of the 17th century and in particular from the 18th century. Amadiya was previously the seat of a large Chaldean diocese which included the Zakho and Akra sectors. In 1850, this diocese was divided into three separate archdiocese.[1]This community and denominational environment was uprooted at the end of the 19th and start of the 20th centuries with the persecution of the Kurds, the implementation of Seyfo[2]by the Young Turks, followed by the break-up of the Ottoman Empire.

During all the rest of the 20th century, and although the Iraqi administration took the lead from 1921, the Chaldeans had no respite. From 1961 to 1991, successive wars opposing the Iraqi regime and the Kurdish Peshmerga weighed heavily on the local Christian communities and their heritage. In the Dohuk-Nohadra governorate, where Amadiya is located, “the outcomes of the Saddam era were terrible for the Christian community in Kurdistan. The so-called protector of the Christians of Baghdad and Basra wiped out the Christian community in Kurdistan. Dozens of extremely ancient churches, rare evidence of the origins of Christianity, were destroyed. Dozens of Christian villages were razed to the ground and their populations deported. Whatever the future for holds for Kurdistan, despite reconstruction attempts, this world has disappeared forever, nothing will bring back the tens of thousands of Christians who emigrated to the west and are now living in Europe or the New World.”[3]This destruction of heritage also constitutes a loss of memory: “if we say that if one hundred churches were blown up (the real figure is of course much higher) this would mean at least two hundred inscriptions would be lost.” This represents a huge loss of knowledge and transmission between generations. This eradication of identity reached its height with the destruction of several monastery, parish and diocesan libraries, as occurred in Amadiya[4].

_______

[1]In « L’Église chaldéenne catholique, autrefois et aujourd’hui ». Extract from the Annuaire Pontifical catholique de 1914, Abbé Joseph Tfinkdji, Chaldean Priest in Mardin, p.70

[2]Seyfo is the Syriac name for the Assyrian Chaldean and Syriac genocide in the Ottoman Empire in 1915-1918.

[3]In « Le livre noir de Saddam Hussein », Chris Kutschera, Oh Éditions, 2005, p.398

[4]In “Recueil des inscriptions syriaques”, Tome 2, Amir Harrak, Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres, 2010, p.533

Amadiya: Chaldean history and demographics

The ancient historical data provided in this chapter is taken from “L’Église chaldéenne catholique, autrefois et aujourd’hui.” Extract from the Annuaire Pontifical catholique de 1914, Abbé Joseph Tfinkdji, Chaldean Priest in Mardin, p.52-54

The first Chaldean bishop of Amadiya,[1]Hnan Jesu was appointed in 1785. Nephew of the patriarch of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East Elie XI, named bishop of this autocephalous eastern church for Amadiya and Djezireh, Hnan Jesu converted to Catholicism and started the line of Chaldean bishops of Amadiya.

Amongst the numerous illustrious bishops of the diocese of Amadiya, Monsignor Joseph Audo, who held the title from 1833 to 1847, went on to become one of the greatest Chaldean patriarchs (1848-1878), under the name of Mar Joseph VI Audo. Another major Chaldean patriarch Raphael I Bidawid (1989-2003) was also bishop of Amadiya from 1957 to 1966.[2]

Amadiya was one of the most dynamic Chaldean dioceses in Iraq. Its large library attests to its influence. Unfortunately, it came to a dramatic end shortly after the Kurdish uprising in 1961, during the time of Monsignor Raphael Bidawid, “my library in Amadiya containing 10,000 volumes and 300 manuscripts was burned down. However, most of our manuscripts were grouped together in Mosul the seat of the patriarchate… After the events in Kurdistan in 1991, Chaldeans who had emigrated to Turkey took with them a number of manuscripts which were sold for small amounts of money to German collectors. In order to preserve the content of the remaining manuscripts, the Vatican suggested taking responsibility for transferring them to microfilm. But the Iraqi government refused to authorise their transfer. Any removal of historic national treasures from the country is a crime which comes with a death sentence in our country.”[3]

In 1913, two years before the Seyfo, there were 4,970 Chaldeans in the Amadiya diocese, including 400 for Amadiya alone. At this time the Chaldean episcopal city was only the fourth largest in demographic terms after Mangesh (1,100 Chaldeans), Araden (650) et Tena (450). For comparative purposes, this diocese also contained 4,000 Nestorian Christians (members of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East). At this point in history there was a large Jewish community in Amadiya and throughout the region.

A century later, in August 2017, the city of Amadiya had a population of 10,000 inhabitants, almost all Kurdish Muslims. Although this Jewish community no longer exists, there is still a synagogue in the city, containing a tomb which local tradition attributes to the prophet Ezekiel, also worshipped by Muslims and Christians. There are an estimated 25 Chaldean Christian families in the city who struggle to preserve the two Christian buildings in the city[4].

_______

[1]The precise name of the diocese is of Amadiya and Chammkan.

[2]Voir http://www.foundation-bidawid.org/fr/index.html

[3]Interview with Patriarch Raphael I Bidawid by Pierre Chartouny and Marc Yared, in Présence Libanaise, April-May-June 1995, Numéro 11. P.45-48

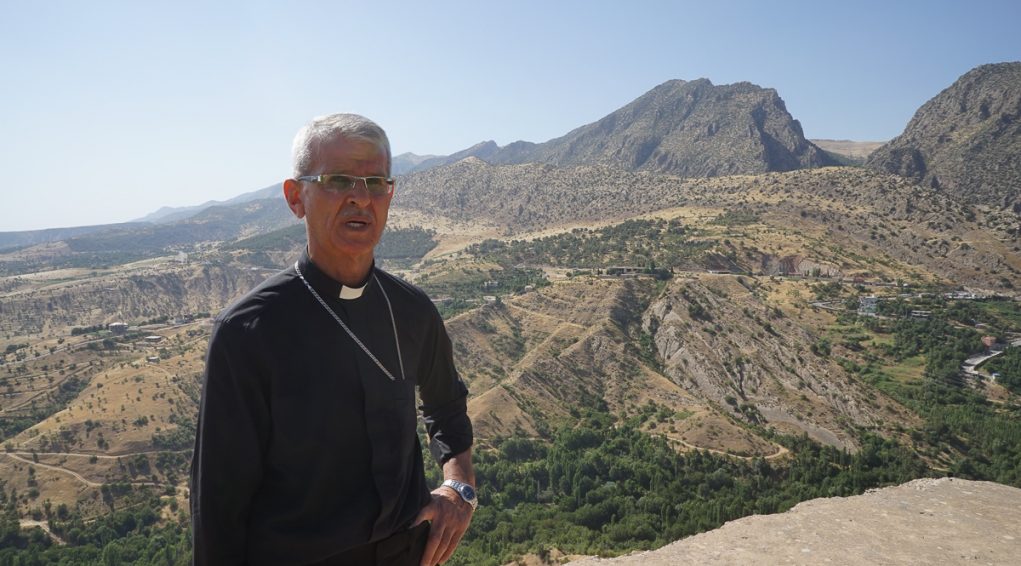

[4]Source: Monsignor Rabban al Qas, bishop of the dioceses of Amadiya and Zakho. Information collected by Mesopotamia on 26 August 2017.

What remains of the Chaldean archdiocese in Amadiya?

There are no external signs of the former archdiocese. After passing through the entrance gate, the visitor arrives in a small, shady internal courtyard. The area appears abandoned. The charmless building, masks below it, at ground level, a small single nave church with a pointed barrel vault. It is not in ruins, but the wall coating has been affected by damp. Two rows of wooden benches and a high altar complete with liturgical furniture attest to the continuity of worship.

Several factors have contributed to the sorry state of this heritage and this community: the library was partially looted and burned down in 1961 at the start of the Kurdish uprising, the archdiocese was bombed in 1963 by Iraqi government forces, the city was partly abandoned during the chemical attacks on Amadiya on 25 August 1988: “Birds fell from the sky and died, the leaves fell from the trees and the trees died. We didn’t see any birds for three years.” Despite its undeniable charm, Amadiya progressively lost its cultural, religious and community vitality[1].

_______

[1]Personal recollection of Monsignor Rabban al Qas, bishop of the dioceses of Amadiya and Zakho, collected by Mesopotamia on 26 August 2017.

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute