The Mar Gorgis Church in Lower Hizanke

The Ancient Church of the East Mar Gorgis church is located at 36°51’40.97″N 43°41’24.21″E and 551 metres altitude in the lower Hizanke village in the Nalha valley.

Whilst in the past there were 23 Assyrian Christian villages in the Nahla valley, only 7 remain today, including the church in Hizanke. In 1988, these villages were destroyed and burned down by Saddam Hussein’s regime, at war with the Kurdish rebels. At the end of the 1990s and start of the 2000s, 200 families returned to the village.

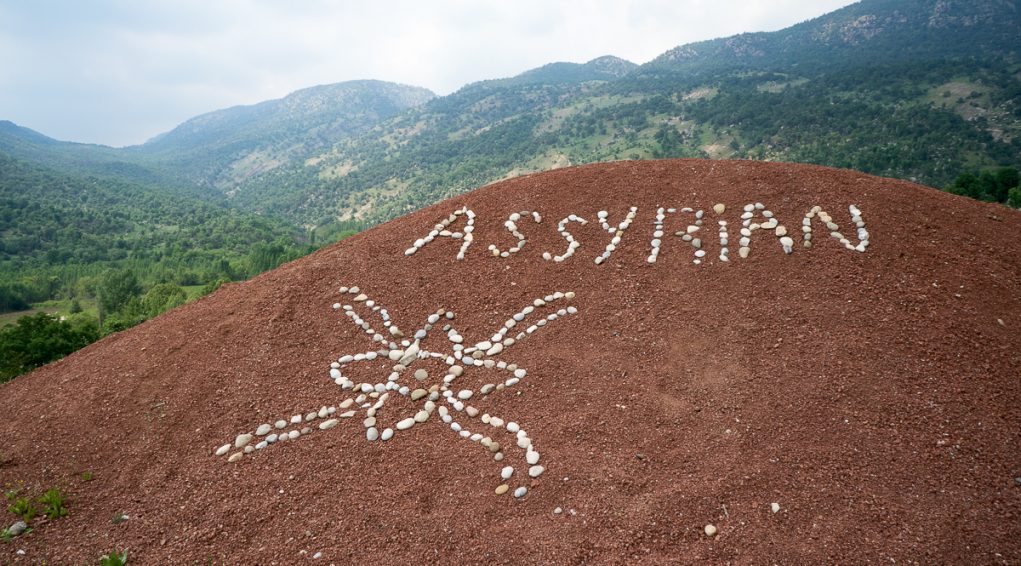

Like the other Christian villages on this high plateau, the community of Hizanke originates from Hakkari (the extreme south-east of Turkey), former patriarchal seat of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East. The inhabitants of Hizanke are thereby descended from the survivors of the 1915 genocide.

The Mar Gorgis church in Hizanke was first built in 1925. Abandoned and re-purposed several times over it was destroyed during the war in 1988. The current Mar Gorgis church was entirely rebuilt in 2005.

Pic : The Assyrian Mar Gorgis church in Lower Hizanke. April 2018 © Pascal Maguesyan / MESOPOTAMIA

Location

The Ancient Church of the East Mar Gorgis church is located at 36°51’40.97″N 43°41’24.21″E and 551 metres altitude in the lower Hizanke village[1]in the Nalha valley. It is actually more of a high plateau than a valley, in a mountain setting.

Crossed by the Khabour river, a tributary of the Tigris, the village of Lower Hizanke is 53 km north-west by road from Aqrah, the main city in the district. Lower Hizanke comes under the authority of the Dohuk-Nohadra province in the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan but borders the province of Nineveh.

_______

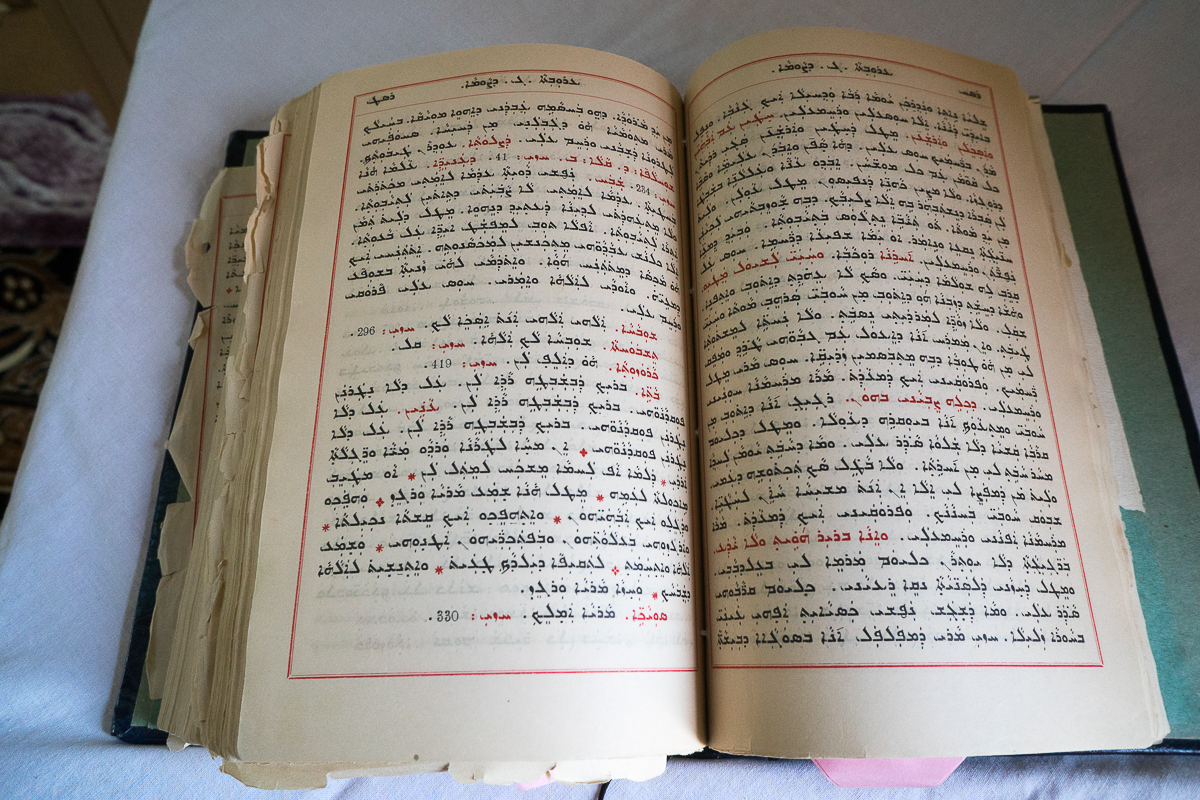

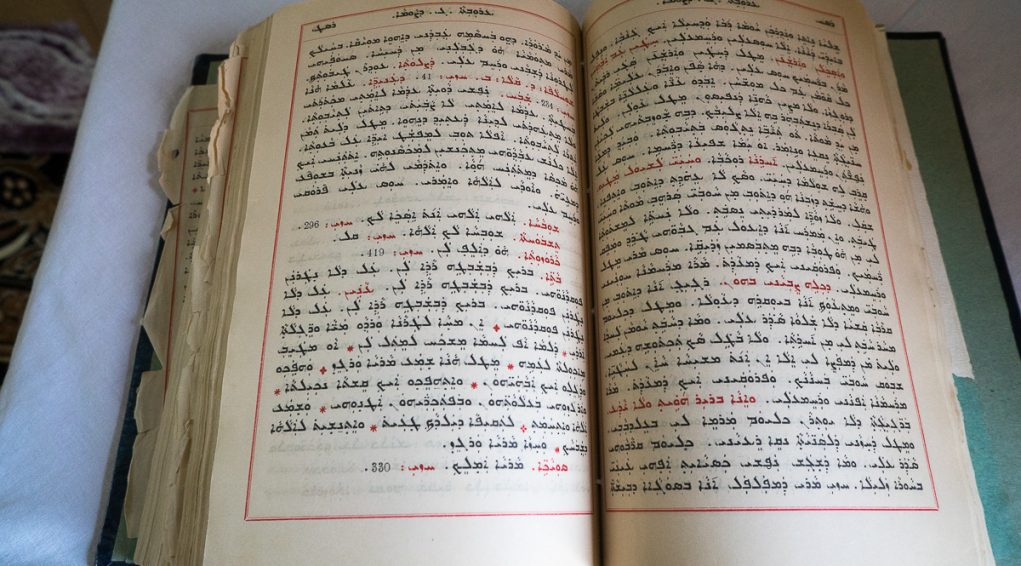

The names of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East

The Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East is known by several names. Here we will simply mention the “Church of the East” in opposition to the Church of the West; “Church of Assyria” and “Church of Meopotamia” which identify its members with these ancient civilisations; “Church of Persia”, as it was under the eponymous Empire that the Eastern Christians structured their geopolitical space and that so many were martyred; and the “Nestorian Church” as it was established by consent with the Christology of the patriarch of Constantinople Nestorius deposed at the Council of Ephesus in 431.

The official denomination Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East is the most complete. Founded and legitimised by the apostle Thomas, the church is proud of its roots in ancient times and places an emphasis on its missionary work.

The name “Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East” was the result of a division dating from 1964 based on the choice of calendar: Gregorian or Julian. The vast majority of Assyrians chose to use the Gregorian calendar, in communion with the other Christians in the region. Those who remained faithful to the Julian calendar formed the Ancient Holy Apostolic Catholic Church of the East. This separation did not alter the sense of belonging to one and the same Church.

Origins of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East

According to the tradition, the origin of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East goes back to the apostles and disciples like Thomas, Addai (some assert that Addai is also the disciple Thaddeus, also known as Jude) and Mari. The tradition also recounts that Thomas “stopped in Seleucia-Ctesiphon during his journey to India.” [1]

The new religion would have been preached especially addressed to local Jewish communities: “It is not known which communities were evangelised, but it is reasonable to assume that the first converts were members of the Jewish community which was predominant throughout Mesopotamia, and even beyond the Tigris, since the deportation of Babylon under Nabuchodonosor. Most likely the greatest efforts to convert people were focused on these Jewish communities, as it already was the case in all cities of the Roman Empire.”[2]

It was really from the 4th century on that the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East started structuring itself in Seleucia-Ctesiphon and almost simultaneously the Persian King Shapur II ushered in an era of anti-Christian persecution, resulting in large numbers of martyrs who are still worshipped centuries later.

In the 5th century, the conflict between the Roman Empire and the Persian Empire, along with Christological disputes between schools of theology, widened the gap between the Churches of the West and the East. After having rejected the conclusions of the Council of Ephesus (431) and welcomed in the patriarch Nestorius, the Church of the East confirmed its break with Rome and Constantinople and asserted its autocephalous nature. This was the second act in the birth of the Church of the East, after it was founded by Saint Thomas.

_______

[1]InHistoire de l’Église de l’Orient, Raymond le Coz, Éditions du Cerf, 1995, p.21

[2]InHistoire de l’Église de l’Orient, Raymond le Coz, Éditions du Cerf, 1995, p.22

Monastic influence and achievements

Throughout the centuries, the high plateaus and mountains of Mesopotamia (south-east of Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan), formerly difficult to access, was a place where the Church of the East flourished and found refuge. The region of Margā (north of Iraq, the region of Aqrah), was home to some of the most influential monasteries of the Church of the East, such as the Rabban Bar ‘Idtā monastery, as well as the Mar Ya’qōb de Bet‘Ābe (Beth’ Abhé)[1]the history of which was written by the illustrious 4th century monk and bishop Thomas de Marga, and which we know was built at the end of the 6th century at the latest. Thanks to the The Book of Governorsby Thomas of Marga there is a rich vein of historic documentation on the Church of the East between the 6th and 9th centuries[2]. In the 9th century there were more than twenty monasteries in the province of Marga. At the start of the 17th century, only four monasteries were mentioned in the region of Aqrah, with around sixty Church of the East Christian villages.

The Syriac-Orthodox church also laid roots in these mountains to the north of Mesopotamia in the 4th and 5th centuries. It developed a vast network of monasteries around the Mar Matta monastery on mount Maqlūb, which is said to have been home to thousands of monks and was known as the “Mountains of Thousands”.

_______

[1]This monastery is next to Aqrah.At the end of the 19th century, the geographer Vital Cuinet saw only a few ruins. See “La Turquie d’Asie. Géographie administrative. Statistique descriptive et raisonnée de chaque province de l’Asie-mineure », second tome. Ernest Leroux publisher, Paris, 1891, p.844-845.

[2]In “The ecclesiastical organisation of the church of the east, 1318 – 1913”, David Wilmshurst, Éditions Peeters (Louvain), 2000, p.155

Fragments of history: the Assyrians from the 16th to the 21st century

In the 16th century, the schism within the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East, engendered the Chaldean Church (in communion with Rome) and caused a major upheaval The majority of Christians in the Apostle Assyrian Church of the East progressively turned to the Chaldean Catholic Church, The consequences of this schism were such that the great Church of the East of the first centuries became “at the end of the Middle Ages, a mere Church-nation”[1], isolated in the mountainous border regions of the Persian (north-west Iran) and Ottoman (extreme south-east of Turkey and north of Iraq) Empires.

Under the Ottoman domination through the 19th century, Kurdish tribes pillaged Christian villages, killing and kidnapping the inhabitants. In 1843 – 1847 the massacres committed were truly horrendous: “The Kurdish Emir of Bohtan Béder-Khan butchered the Assyrians and Chaldeans in the province of Van. Over 10,000 men were massacred, thousands of women and young girls kidnapped and forced to convert to Islam, all the Assyrians and Chaldeans possessions and villages were burned to the ground.”[2] In 1894-1896 the nature of the massacres of the Christians (Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans and Syriacs) changed. These were organised at the highest levels of the empire by Sultan Abdul Hamid II, known as the Red Sultan, who sent out his hamidiyé to attack Christian locations. This genocide left the Christian communities almost wiped out of existence.

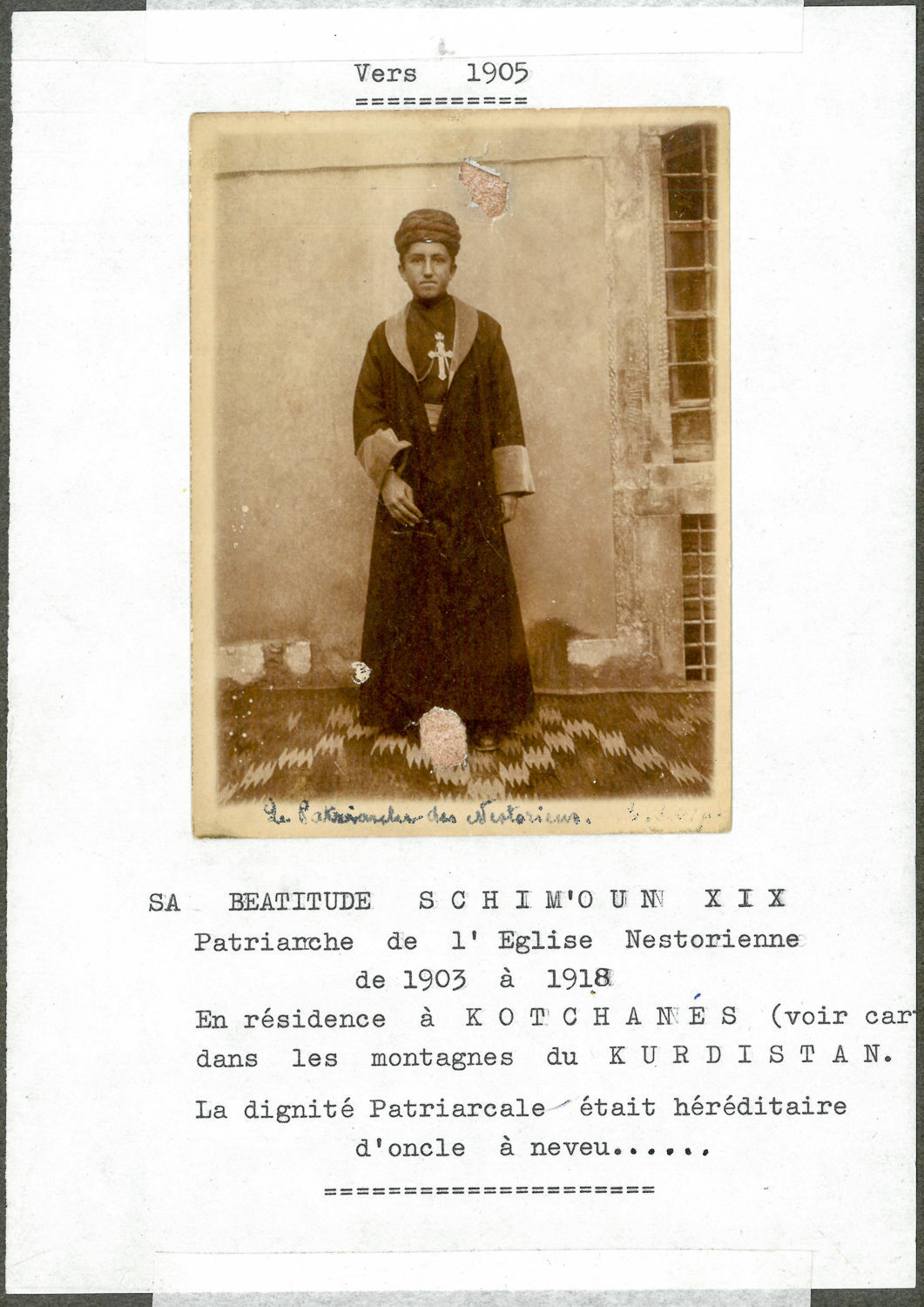

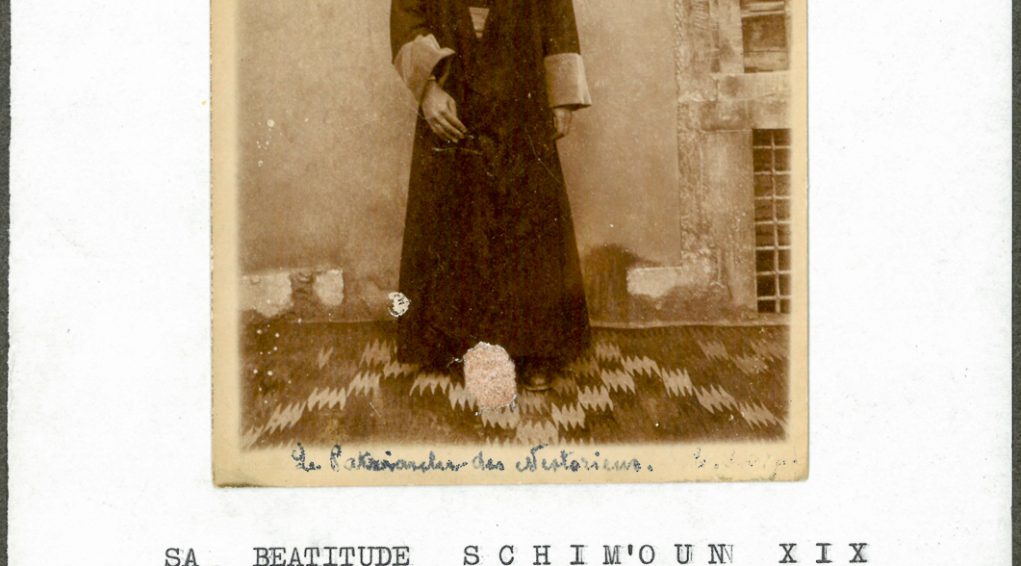

When the nationalist Young-Turkrevolution overthrew the Sultan in 1908, Christians in the Empire were filled with the desperate hope of a change in fortunes. This was illusory. As of 1909, the Adana massacres constituted the prelude to the systematic, planned destruction of the Christian communities, carried out under the cover of the First World War from 1915 – 1917. From the very start of the war, in the autumn of 1914, Turkish and Kurdish troops entered into Persia and massacred the Assyrian and Chaldean communities in the Ourmiah district. In April 1915, when the genocide of the Armenians began in the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire, 150,000 Assyrian survivors grouped together in the Hakkari mountains (extreme south-east of Turkey) from the vilayetof Van around the patriarchal seat of Kotchanes[3](since 1662), residence of the Catholicos Mar Schemoun “member of the family of the same name, guarantor of the traditions and nepotism exercised within it since 1450.”[4]The Hakkari Assyrians resisted their Turkish and Kurdish attackers ferociously, but were forced into exodus into Persia. “They crossed the high mountains towards Salamas in Iran on 7 – 8 October 1915. The survivors, 50,000 out of 100,000 arrived exhausted[5]. They were taken in by the Russian army and their compatriots (…) But the local population was against them and their compatriots living there were ruined.” From 1915 to 1917, the massacres of the Armenians, Syriacs, Chaldeans and Assyrians continued and intensified, spreading to all the towns and villages in the Ottoman provinces of Van, Bitlis, Mamuretulaziz, Erzeroum, Diyabakir et Aleppo. These horrific massacres led to a mass exodus which killed even more people as they headed for the deserts of Syria and Mesopotamia. During the summer of 1918, abandoned by their Russian protectors “around eighty thousand Assyrians and Chaldeans, with their cattle and their belongings”[6]once again took to the road from Ourmiah, towards Hamadan in Persia, before finally arriving in Mesopotamia in Bakouba (50 km north-east of Baghdad). Half of the displaced population perished during this further ordeal.

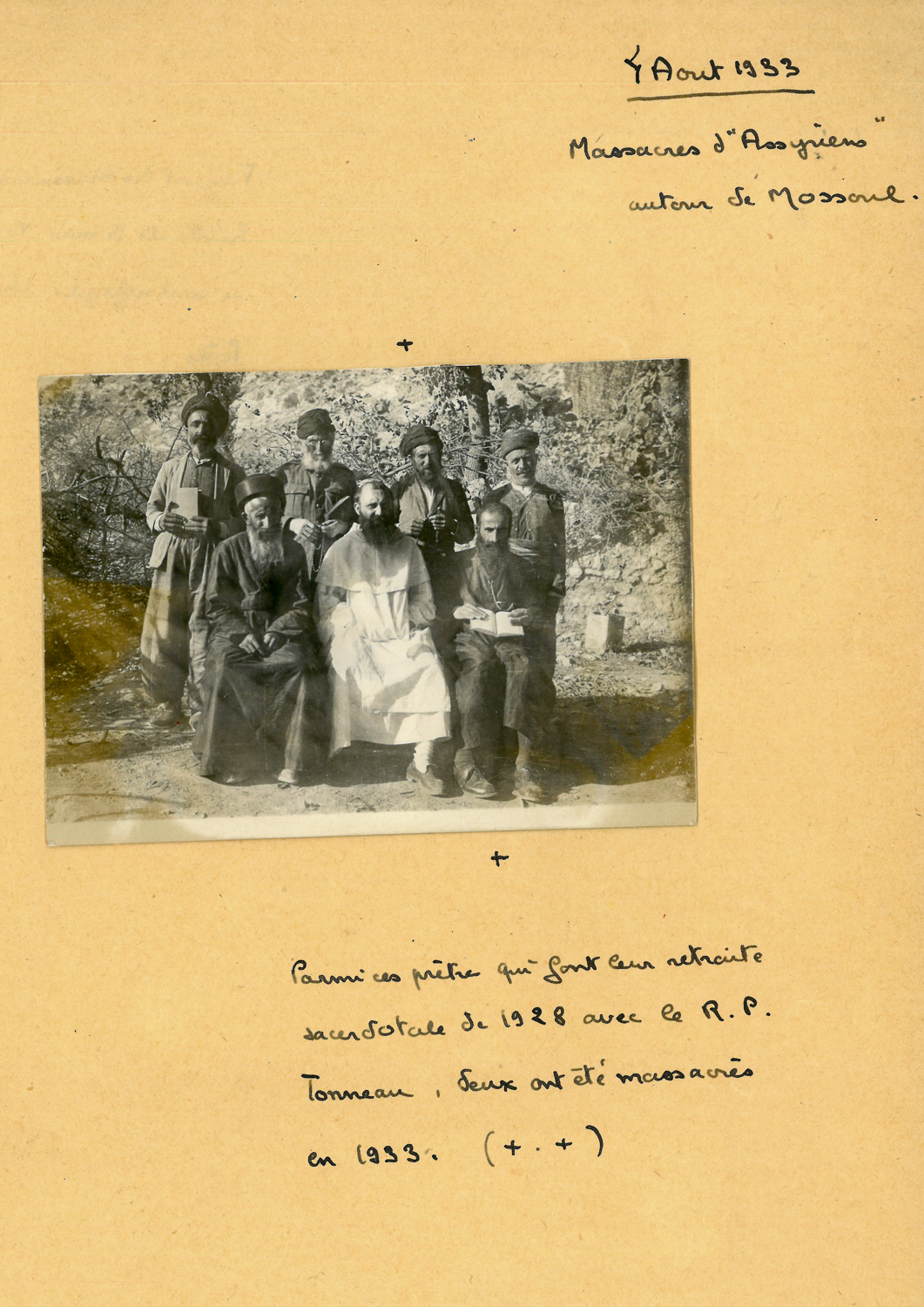

In Mesopotamia under British rule, the Assyrians were used as combat troops, the Assyrian Levies,who helped to maintain order whilst hoping this would see them awarded political favours for the Assyrian Chaldean nation. “Rather than a State, the still-born treaty of Sèvres signed on 10 August 1920, signed between Turkey and associated allied powers, only afforded the Assyrian-Chaldeans guarantees and protection as part of a future autonomous Kurdistan. The treaty never came into force.”[7] The 6,500 Assyrians commanded by General Agha Petros could only count on themselves and attempted to take back Hakkari in October 1920 but this degenerated into a punitive and ultimately fruitless expedition. In 1923, the Lausanne treaty killed off the Assyrians and Armenians illusions of autonomous rule, simultaneously ruling out any chance of return. When the British mandate came to an end and Iraq became independent on 3 October 1932, the Iraqi authorities wanted to disperse the Assyrian Chaldeans. The Assyrians refused and entered into resistance. A thousand of them took up arms and travelled to Syria which was under French rule at this time, in July 1933, with a view to negotiating the collective, long-term settlement of their community. When they returned to Iraq at the beginning of August, via the village of Feshkhabour to collect their families, the Assyrian fighters were shot down by King Faisal’s troops but they managed to defeat the Iraqi forces. This affront caused Iraqi troops to take their revenge against the Assyrian-Chaldaen villagers of Simele, close to Dohuk. The massacre began on 8 August 1933, with help from the Kurdish tribes. Three thousand men, women and children had been killed by 11th August. “The Arab officers and soldiers who committed these crimes were promoted and received a triumphant welcome in Mosul and Baghdad; their leaders, the Kurdish Colonel Baker Sedqi, was made a General.”[8]

The rest of the 20th century was not much better for the Assyrian-Chaldeans. During the Second World War, new Assyrian combat units contributed to the British war effort against an Iraqi government supported by Nazi Germany. They obtained no diplomatic rewards.

As of 1961, and up until 2003, the successive civil wars opposing Kurdish separatists and the Baghdad government had an appalling effect on the Assyrian-Chaldean Christian communities in the north of the country: killings, blackmail, destruction of heritage, forced population displacements, forced Arabisation, gas attacks etc.

In 2003, end of the tyrannical regime of Saddam Hussein, marked the start of a chaotic period of Islamism and organised crime, during which criminal groups such as Al-Quaeda and ISIS persecuted Christian communities. Against all expectations, in the Kurdish mountains, the Assyrians and other Christians of Iraq benefited from a historic period of respite, thanks to the benevolence of the Kurdish regional government which implemented policy favouring the reinstallation of native-speaking Christian communities. The Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East can finally look to the future.

_______

[1]In “Du génocide à la diaspora : les assyro-chaldéens au XXesiècle”, Joseph Alichoran, Article published in the review Istina, 1994, N°4, October-December, p.4

[2]Eugène Griselle in “Qui s’en souviendra ? 1915 :le génocide assyro-chaldéo-syriaque.”, Joseph Yacoub, Les éditions du Cerf,, p.128

[3]In 1988, nothing remained of this patriarcate other than the patriarchal church Mar Shallita, built in 1689 and in poor condition. What remains in 2018? Source Joseph Alichoran.

[4]In “Du génocide à la diaspora : les assyro-chaldéens au XXesiècle”, Joseph Alichoran, Article published in the review Istina, 1994, N°4, October-December, p.5

[5]In “Qui s’en souviendra ? 1915 :le génocide assyro-chaldéo-syriaque.”, Joseph Yacoub, Les éditions du Cerf, p.149

[6]In “Du génocide à la diaspora : les assyro-chaldéens au XXe siècle”, Joseph Alichoran, Article published in the review Istina, 1994, N°4, October-December, p.22

[7]In “Du génocide à la diaspora : les assyro-chaldéens au XXesiècle”, Joseph Alichoran, Article published in the review Istina, 1994, N°4, October-December, p.24

[8]In “Du génocide à la diaspora : les assyro-chaldéens au XXesiècle”, Joseph Alichoran, Article published in the review Istina, 1994, N°4, October-December, p.29

A brief history of Assyrian Christians in the Nahla valley

Whilst in the past there were 23 Assyrian Christian villages in the Nahla valley, only 7 remain today: upper and lower Hizanke, upper and lower Chole, Belmande, Khelelane, Kchkava, Meroke, Chamra-Badke.[1]

In 1988, these villages were destroyed and burned down by Saddam Hussein’s regime, at war with the Kurdish rebels. The 500 Assyrian Christian families in the high plateaus were forced to evacuate for the third time and resettled in Aqrah, Mosul, and Baghdad. At the end of the 1990s and start of the 2000s, 200 families returned to the village as the autonomy of Iraqi Kurdistan was recognised and persecution by Islamicist and organised crime groups increased in Baghdad, Mosul and the Nineveh plain.

Like the other Christian villages on this mountain plateau, the community of Lower Hizanke comes from Tiari in Hakkari (see previous section Fragments of history: Assyrians in the 16th and 17th centuries), the former territorial and patriarchal seat of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East. The inhabitants of Hizanke are thereby descended from the survivors of the 1915 genocide.

_______

[1]Source Benyamin Yalda Icho, originally from Hizanke, interviewed on 22 July 2017 in Aqrah by the Mesopotamia team.

Assyrian demographics in Iraq

At the end of the 19th century and on the eve of the First World War, the Assyrian nation was estimated at one million people in Iraq, Iran and Turkey. In 1957, there were 750,000 to 1 million in Iraq. At the start of the 1970s, this figure fell to 300,000. In 2017, there were less than 40,000. This demographic collapse is the consequence of a series of historic disasters.

The main Assyrian populations in Iraq are found in Dohuk-Nohadra where there are 2,000 families. Around Dohuk-Nohadra, in the districts of Barwar, Semel, Zakho and Amadia, there are 1,500 families spread across 55 villages. In total, the province of Dohuk-Nohadra is home to around 20,000 Assyrians. [1]

Four major monasteries of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East remain: Mar Odisho in Dere, Mar Qayouma in Kani Massi Doure, Mar Gorgis in Kani Massi Iyed and Mar Mouche in Kani Massi Tchelek.

_______

[1]Source: Khoury Philippos, archpriest of the Mar Narsaï church in Dohuk-Nohadra part of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East.

History and description of the Mar Gorgis church in Lower Hizanke

The Mar Gorgis church in Lower Hizanke was first built in 1925. Abandoned and re-purposed several times over it was destroyed during the war in 1988. The current Mar Gorgis church in Lower Hizanke was entirely rebuilt in 2005, thanks to funding from the Assyrian benefactor and former minister Sarkis Aghajan.

It is the parish church for four villages in the sector, directly reporting to the Baghdad diocese.

The church is too small to celebrate major community and religious festivals so worshippers have to use a hall.

Built on a belvedere overlooking the plain to the west, the building is built of natural stone blocks and concrete. The church has a longitudinal, cross-shaped layout. The radiating entrance door is located on the south facade. Inside, the church has a single nave, with a three-part ceiling. The walls and ceilings are covered in decorative PVC panels. The floor is tiled. The sanctuary, raised with three steps, is accessed via a holy door with three openings. The central arch is as large as the altar alongside the wall of the radiating apse. On the side aisles, the narrow, curtained openings converge to the south towards the baptismal font and on left to the sacristy. The two radiating rooms form the arms of the cross. Above the sanctuary, the building is mounted with a rectangular drum dome, perforated with a window in the shape of an Assyrian cross.

Life account

Abouna Andraos Mikhaël is the archpriest of the Assyrian Christian villages in the Nahla valley and Aqrah for the Ancient Church of the East. Married, with four children, he trained at the Sarsink seminary and was ordained in 1973 in Kirkuk and became chorbishop in 1988. He came to Lower Hizanke in 2003. In the Nahla valley, winters are harsh and the summers scorching. The Assyrian families live off arable and livestock farming. They also produce poplar wood for the construction industry. There is only one obstacle to this rural life: “We are happy in the mountains, but the Kurds want to take our land!” Relations between the Assyrian Christians and Kurds are still today tense and sometimes conflictual.

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute