The Mariam Al Adra Cathedral in Aqrah

The Mariam al Adra cathedral is located at 36°45’38.2″N 43°53’42.5″E and 799 metres altitude on a ledge at the foot of the cliff which overlooks the city of Aqrah.

The Mariam al Adra cathedral was built in upper Aqrah, on a ledge of the cliff on the flank of which the Christians lived. We do not know the date of its initial construction. It is attested to in a manuscript from 1695.

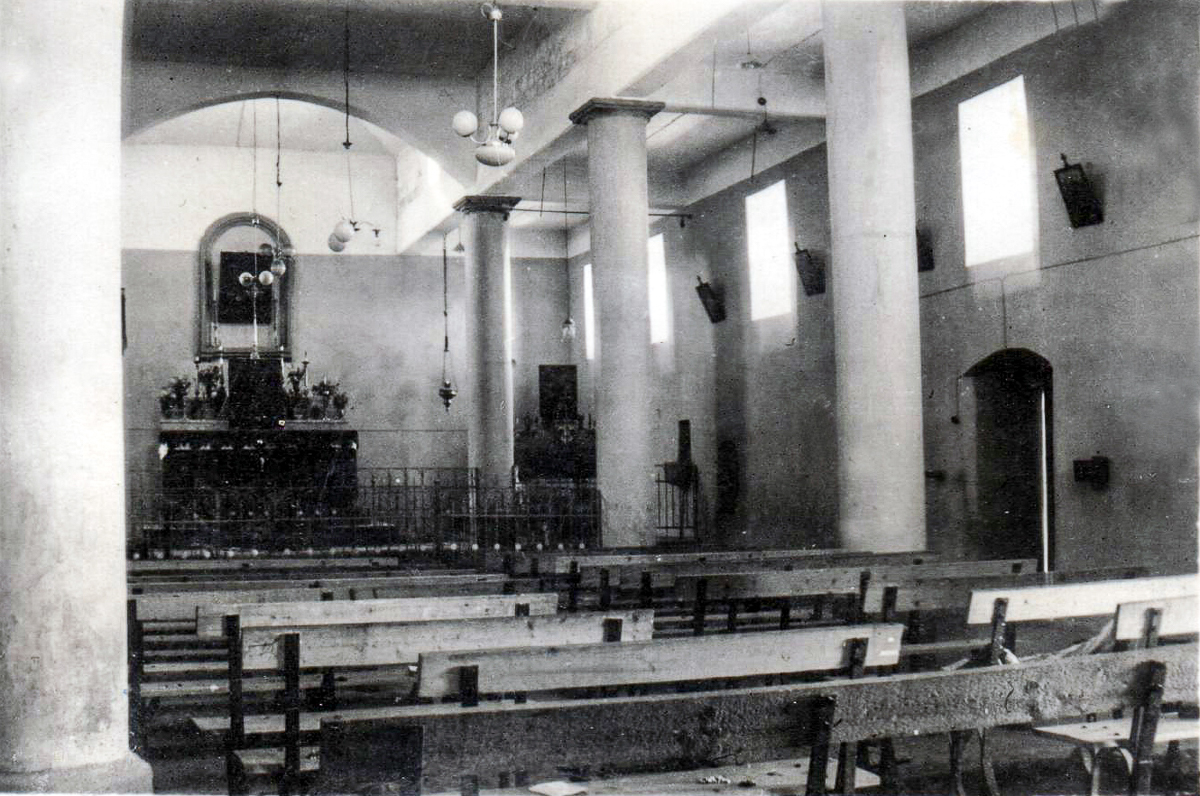

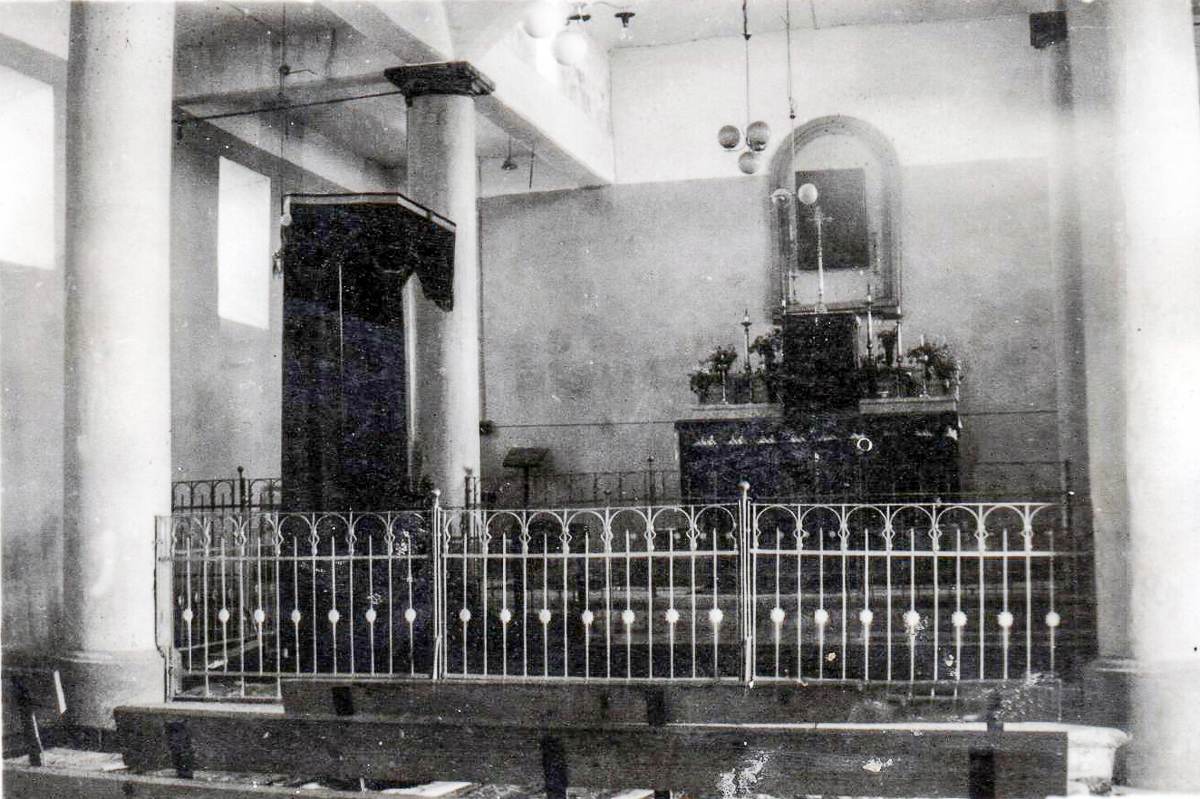

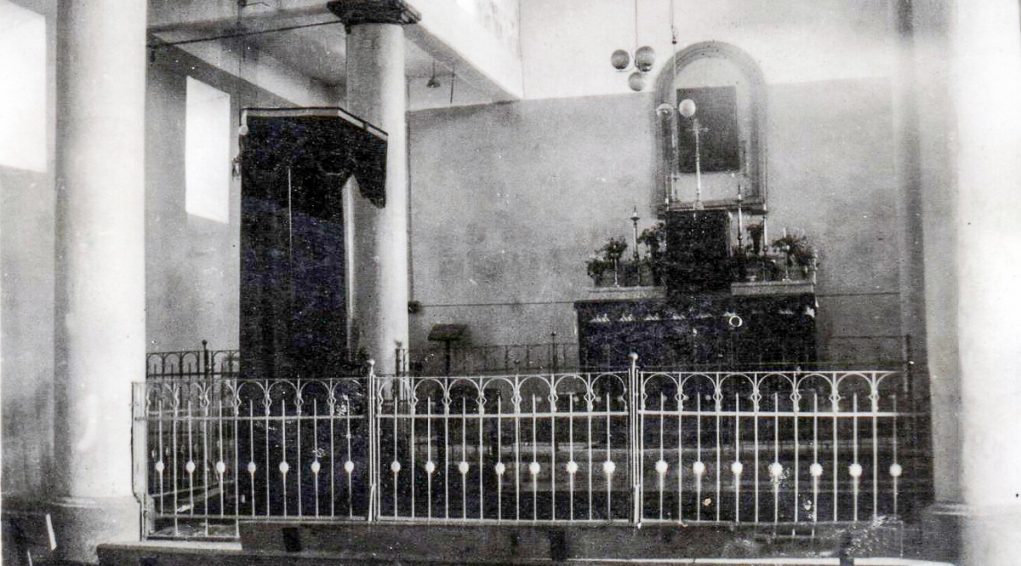

The Mariam al Adra cathedral in Aqrah covers around 100 m². It is a three-nave basilica church, formed of four pairs of freestanding cylindrical pillars which support the ceiling, the central part of which is slightly higher than the side aisles. The high altar with steps, which practically rests on the eastern wall, was almost totally destroyed. The altar in the south wing has also been partially destroyed. In the north wing there is no trace of an altar.

Pic : The Mariam al Adra cathedral in Aqrah. July 2017 © Pascal Maguesyan / MESOPOTAMIA

Location

The Mariam al Adra cathedral is located at 36°45’38.2″N 43°53’42.5″E and 799 metres altitude on a ledge at the foot of the cliff which overlooks the city of Aqrah[1].

Aqrah, to the west of Great Zab backs onto the mountain range of Chindar which borders Iraqi Kurdistan. The city is also 96 km to the east of Dohuk-Nohadra and 80 km north of Erbil.

Aqrah is an extremely ancient city, built on the terraces in the cliff face which overlooks the ancient citadel destroyed in 1840. There are also numerous gardens and waterfalls, as well as ancient traditional houses built of stone and earth.

_______

Fragments of Christian history

According to the tradition, the origin of the Church of the East goes back to the apostles and evangelizing preachers like Thomas, Addai (some assert that Addai is also the disciple Thaddeus, also known as Jude) and Mari. The new religion would have been preached specifically to local Jewish communities. The city of Aqrah is known for having a thriving Jewish community up until the 1940s, of which numerous traces of its heritage remain[1].

This Christianity born out of this apostolic tradition, spread around Mesopotamia during the three first centuries, but it was really from the 4th century on and with the large number of martyrs persecuted by the Persian king Shapur II, that the Assyrian Church of the East really stepped into local history.

Over the centuries, the mountains which used to be very difficult to access were a place of fulfilment and protection for the Church of the East. The region of Aqrah, known as the province of Margā, was home to some of the most influential monasteries of the Church of the East, such as the Rabban Bar ‘Idtā monastery, as well as the Mar Ya’qōb de Bet‘Ābe (Beth’ Abhé)[2]the history of which was written by the illustrious 4th century monk and bishop Thomas de Marga, and which we know was built at the end of the 6th century at the latest. Thanks to the The Book of Governorsby Thomas of Marga there is a rich vein of historic documentation on the Church of the East between the 6th and 9th centuries[3]. In the 9th century there were more than twenty monasteries, about which little is known, in the province of Marga. Only two of them are mentioned in sources dating from later than the 10th century. At the start of the 17th century, only four monasteries were mentioned in the region of Aqrah, with around sixty Church of the East Christian villages.

The Catholic, specifically Dominican, missions flourished here from the 18th century onwards and converted numerous local Christian communities to Catholicism, which moved from the Church of the East to the Chaldean church, mainly from the start of the 19th century. Up until 1850, Aqrah, Zakho and Amadia formed one single Chaldean diocese called Amadia. It was at this time that they were divided into three separate archdioceses and the diocese of Aqrah was created.[4]

At the start of the 20th century, on the eve of the First World War, Aqrah was the capital of the Ottoman caza in the vilayetof Mosul. The circumstances of the Christians in the most remote regions of the Empire worsened in the 19th century, mainly due to the raids perpetrated by the Kurds, and became catastrophic during the genocide of the Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans and Syriacs in the Ottoman Empire from 1915-1918.

The rest of the 20th century was not much better for the Assyrian-Chaldeans from the mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan. Between 1961 and 1991, the successive wars which opposed the Iraqi government and the Kurdish peshmerga weighed heavily on the Christian communities and their heritage in these regions which were frequently bombed, notably with chemical weapons, where the populations were evacuated on several occasions and access was prohibited for a long period of time.

In the 21st century, the ISIS offensive on the Nineveh plain in August 2014, forced hundreds of Christian families to seek temporary shelter in Aqrah.

_______

[2]This monastery is next to Aqrah.At the end of the 19th century, the geographer Vital Cuinet saw only a few ruins. See “La Turquie d’Asie. Géographie administrative. Statistique descriptive et raisonnée de chaque province de l’Asie-mineure », second tome. Ernest Leroux publisher, Paris, 1891, p.844-845.

[3]In « The ecclesiastical organisation of the church of the east, 1318 – 1913 », David Wilmshurst, Éditions Peeters (Louvain), 2000, p.155

[4]In « L’Église chaldéenne catholique, autrefois et aujourd’hui ». Extract from the Annuaire Pontifical catholique de 1914, Abbé Joseph Tfinkdji, Chaldean Priest in Mardin, p.70

Christian demographics in Aqrah

At the end of the 19th century, from 1890-1891, there were 4,700 inhabitants in Aqrah, including 4,150 Muslims, 300 Israelites[1]and 250 Christians (Chaldeans and Jacobites[2]). The Chaldeans had small school of 15 pupils: “The schools in the mountains are the most basic facilities you can imagine. The schoolhouse is the church. The children sit along the wall, on mats and the teacher stands in the middle.[3]”The Jacobites had no school or priest. They met together and held services in a “sort of chapel or cave dug into the rock.[4]” This is the troglodyte Mar Gorgis church above the Mariam al Adra cathedral.

Beyond the city limits, in the cazaof Aqrah, there were 81 villages for 11,000 inhabitants: 10,150 Muslim Kurds, 550 Chaldean and Jacobite Christians and 300 Israelites.

In 1913, the demographics had hardly changed. In Aqrah there is still a Christian community of 250 people (mainly Chaldean), with two priests, a church and a school[5]. This statistic was the same in 1961[6]before the start of the war between the Kurds and the government in Baghdad. The Christians of Aqrah temporarily left the city in 1963 under the fire of the invading Arab forces. They were joined in the 1980s by Assyrian Christian families from the high plateaus of Nahla, whose 7 villages were destroyed and burned by Saddam Hussein. At the start of the 21st century, a new Christian community formed in Aqrah made up of the displaced people from the Nineveh plain who arrived in August 2014, fleeing the ISIS offensive. Of the 500 – 600 displaced families, only 100 remained in July 2017. This figure will no doubt have continued to decrease.

_______

[1]Israelite was the name used to designate Jews at this time.

[2]The Jacobites are part of the Syriac-Orthodox church.

[3]See“La Turquie d’Asie. Géographie administrative. Statistique descriptive et raisonnée de chaque province de l’Asie-mineure », second tome, Vital Cuinet. Ernest Leroux publisher, Paris, 1891, p.843.

[5]InL’Église chaldéenne catholique, autrefois et aujourd’hui, Abbé Joseph Tfinkdji, 1913, Extract from the Annuaire Pontifical Catholique from 1914, p. 51

[6]In “Assyrie Chrétienne”, vol II, Imprimerie catholique de Beyrtouth, J.M.Fiey, p.266

History of the Mariam al Adra cathedral in Aqrah

The property of the Church of the East before being transferred to the Chaldean church, the Mariam al Adra cathedral was built in upper Aqrah, on a ledge on the flank of the cliff-face where the Christians lived. We do not know the date of its initial construction. It is attested to in a manuscript from 1695. Around 1890-1891, it was “almost entirely in ruins.[1]”Services were held in a “private house.[2]”The bishop of Aqrah, Monsignor Paulos Cheikho (the future Chaldean patriarch) had the church built in 1955. He also had a new archdiocese built, a new school and a monastery for the Sisters of Saint Catherine.

The cathedral was abandoned in 1963, after the Christians left due to the war. It was never renovated.

_______

[1]In “Assyrie Chrétienne”, vol II, Imprimerie catholique de Beyrtouth, J.M.Fiey, p.266

Description of the Mariam al Adra cathedral in Aqrah

If you want to visit the Mariam al Adra cathedral in Aqrah, you will need to ask the caretaker of the Muslim cemetery[1]who has the key.

The Mariam al Adra cathedral in Aqrah covers around 100 m². It is a three-nave basilica church, formed of four pairs of freestanding cylindrical pillars which support the ceiling, the central part of which is slightly higher than the side aisles.

The building has very thick walls. Viewed from the exterior, they are formed of quarry stones. Viewed from the interior they are composed of stones covered in a thick coating.

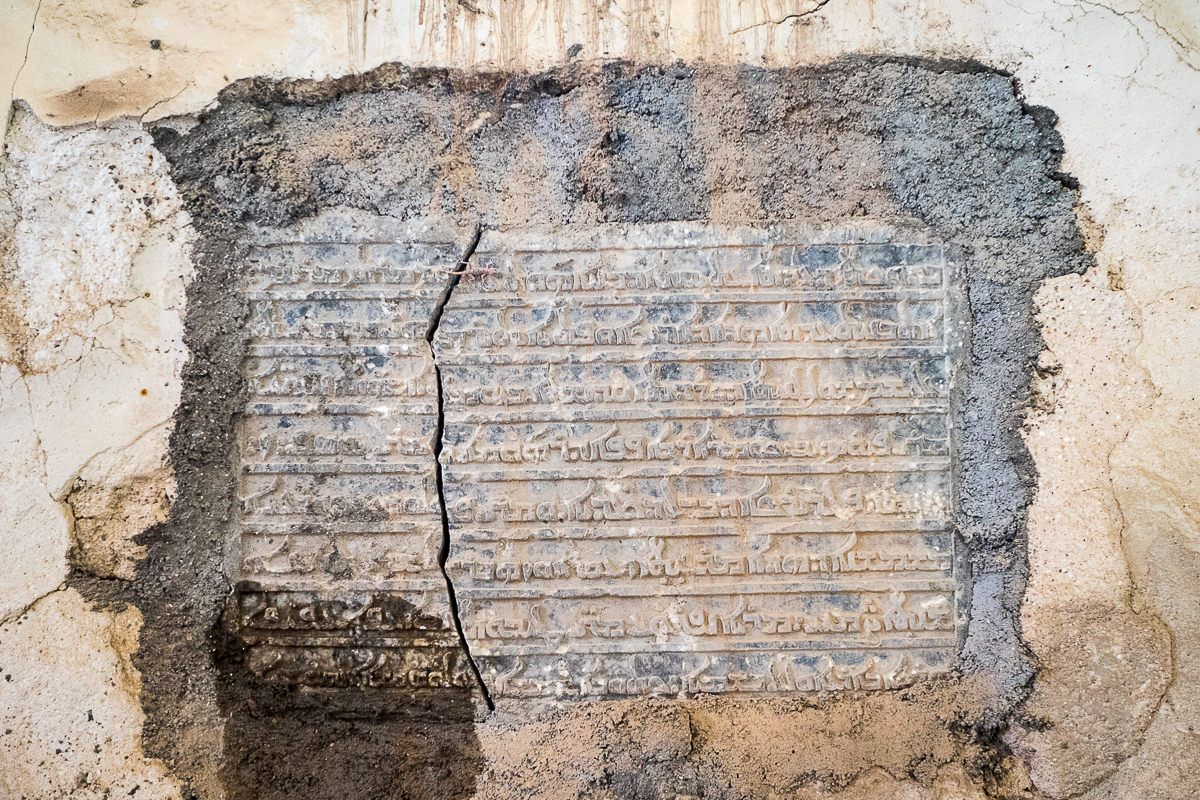

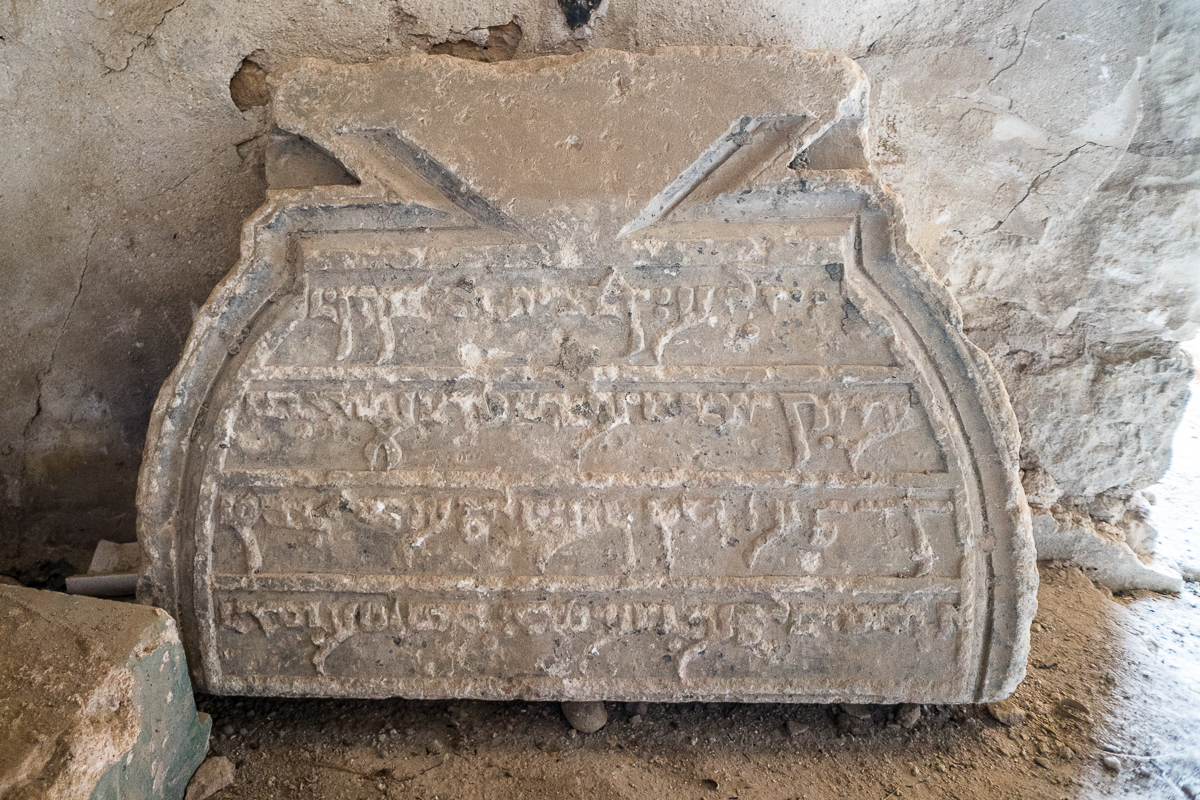

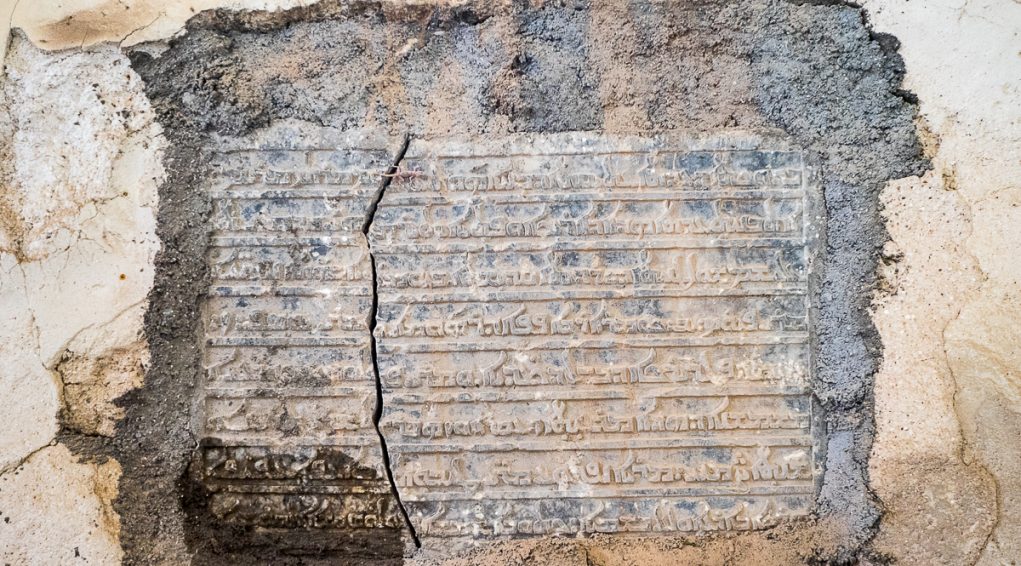

On the north and south facades are two marble plaques engraved with Syriac inscriptions, as well as a marble plaque adorned with a coat of arms.

The nave is separated from the choir by a step with no royal door, and there is no visible choir screen. The sanctuary is also separated from the choir by a simple step.

The high altar with steps, which practically rests on the eastern wall, was almost totally destroyed. The altar in the south wing has also been partially destroyed. In the north wing there is no trace of an altar.

On the south wall is a coat of arms, as well as a marble plaque engraved with Syriac inscriptions. On the north wall is another engraved plaque. One of these broken plaques has an inscription in Estrangelo Syriac which reads “Soultanat al Wardina al moukadasa” meaning “Our Lady of the Holy Rosary”.

The tiled floor of the cathedral has disappeared, no doubt stolen.

In front of the church is a lower level esplanade where the remains of stone perimeter wall are found, including the entrance door to the south-west, made of quarry stones, with a semi-circular arch, this door also bears Syriac inscriptions.

_______

[1] The caretaker on the day Mesopotamia visited on 16th July 2017 was Mohammed Rejab.

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute