Rabban Hormizd Monastery

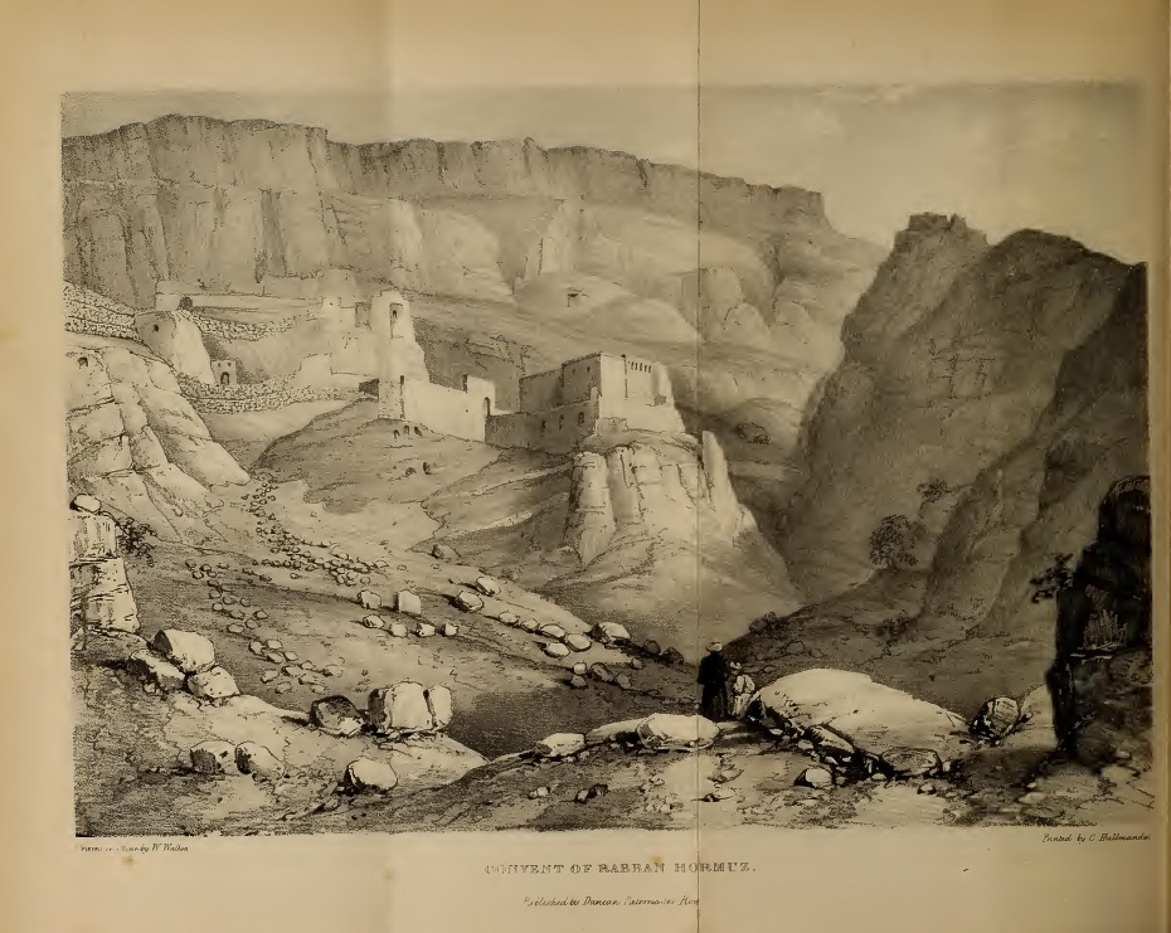

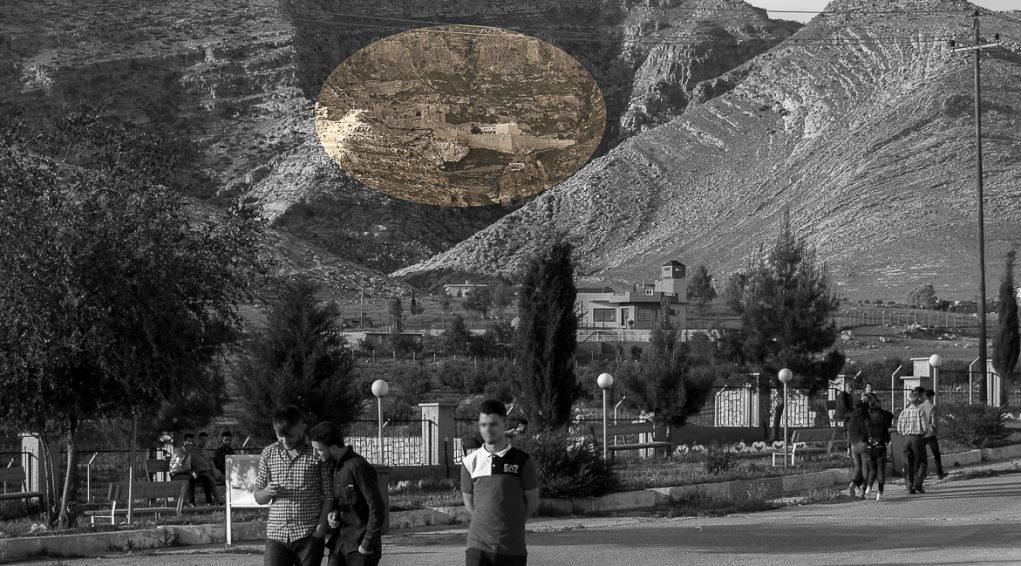

Rabban Hormizd monastery, in Alqosh, lies at 36°44’56.5’’ N 43°06’53.97’’ E ; 815 metres high.

Established in the 7th century, it is one of the most ancient Christian monasteries in Iraq.

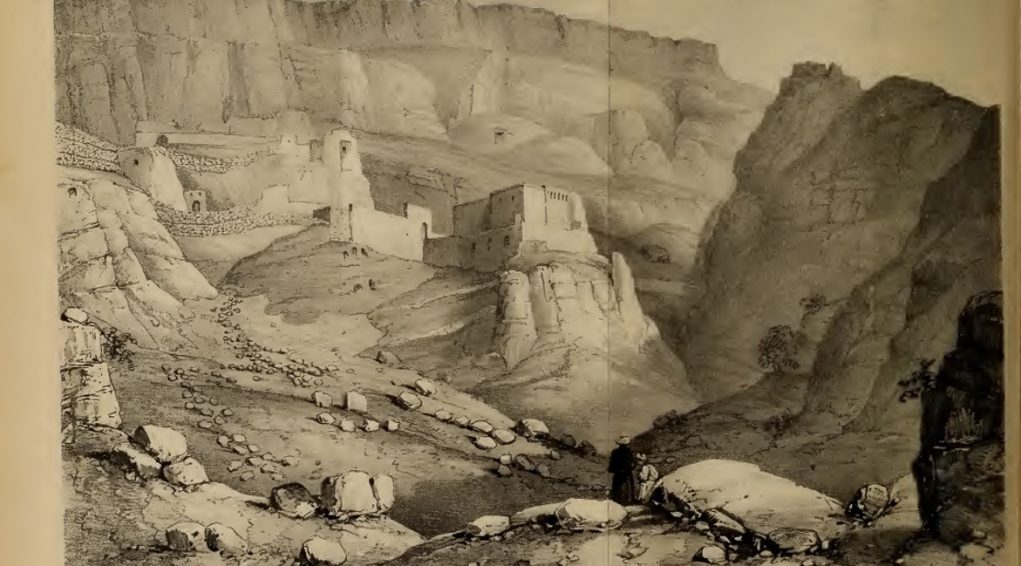

Carved out in the mountain range that lines antique Assyria and runs along the international borders of Iraq, Turkey and Iran, the monastery of Rabban Hormizd is the symbol of the unstable history of Christianity in Mesopotamia.

Situation

Rabban Hormizd monastery is situated in the North of the Nineveh province, at the border of the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan, 36°44’56.5’’ N and 43°06’53.97’’ E.

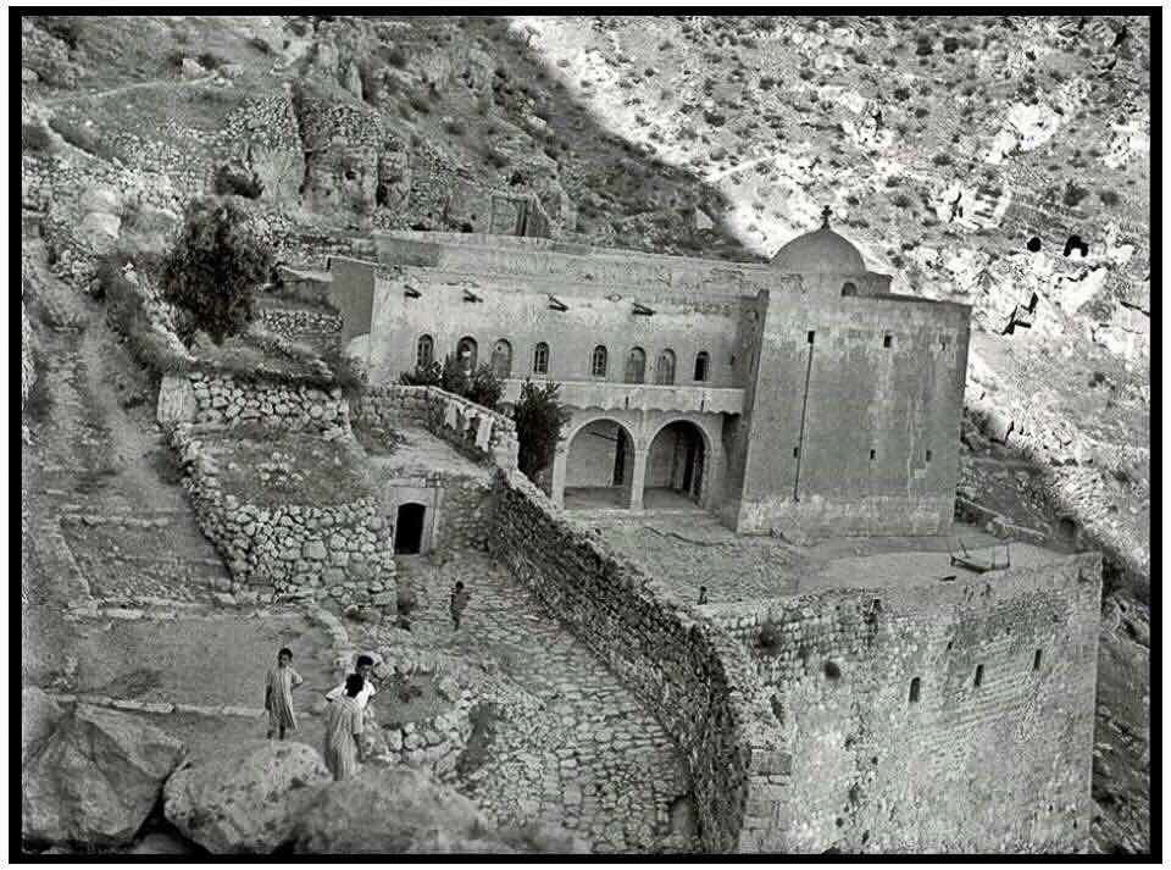

It is built half way up the mountain range, 815 meters high, 2 km North-East from Alqosh city centre and 2 km North-West from the Yazidi village of Bozan. The monastery benefits from a noteworthy geographical situation, 10 km away from the Tigris on its eastern bank. Southward, it overlooks the arid horizon of the Nineveh plain. Mosul is just 40 km as the crow flies. Towards the North, it is carved out in the mountain range which lines antique Assyria and runs along the nowadays international borders of Iraq, Turkey and Iran. The monastery seems like a pearl in its case. Over the centuries, local geopolitical rivalries have often disrupted the site’s peacefulness, though essential to monastic life.

History

Founded in the 7th century, Rabban Hormizd monastery may have been consecrated during the patriarchate of Ishoyahb II (628-644/47), in other words “during the years of the Muslim conquest” as Joseph Habbi writes in his monography about the monastery. This date is actually being debated by the orientalist and Dominican Jean-Maurice Fiey in his work Assyrie Chrétienne (vol.II, page 534, Imprimerie Catholique de Beyrouth). He assumes that the Catholicos Tomarsa, who came to consecrate the monastery, lived at the end of the 4th century. So the monastery’s foundation may well be much earlier than it is often admitted.

Who was Rabban Hormizd ?

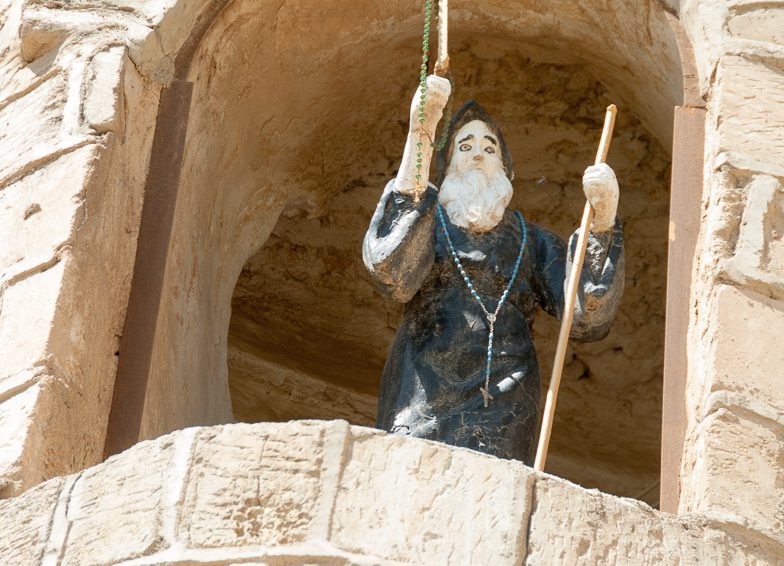

According to some sources, Rabban Hormizd was of Persian origin. His hagiography relates that while he was making a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, Persian Hormizd came to Mosul where he met with three monks “who made him change his way and go with them eastward, in the country of Marga, to Bar ‘Éta Monastery” reports Jean-Maurice Fiey. He became a monk and lived there for 39 years, 32 of which cloistered as a hermit. After that, his reported wanderings led him to the Réša monastery (Resha – Mōr Abrōhōm) up in the mount Maqlub with a small group of fellow travellers, where they settled for 6 or 7 years. After this time, the group split. Hormizd and disciple Abraham climbed to another summit, B.’Edrai. After Abraham had left his master to go and found his own convent in Bātnāya, Hormizd remained alone in a cave. He probably has welcomed some visitors and pilgrims, seeking for miraculous healing. He is still appealed to nowadays, as thaumaturge or wonderworker.

He died aged 90, “25 years after the foundation of his monastery who hosted then about 100 monks”. The monk and Nestorian Rabban Hormizd was commemorated the third Monday after Easter and on August 15th. However there has been confusion between the Roman Catholic Church and the Church of the East with another homonymous Rabban Hormizd, Persian-Chaldean martyr in the 5th century. The Nestorians had reassigned the commemoration of the 3rd Monday after Easter to another martyr so they eventually attributed September 1st as Feast Day for Rabban Hormizd in their synaxarion, in recognition to the miraculous healing of a blind man in the 9th century, 2 centuries after the monk died.

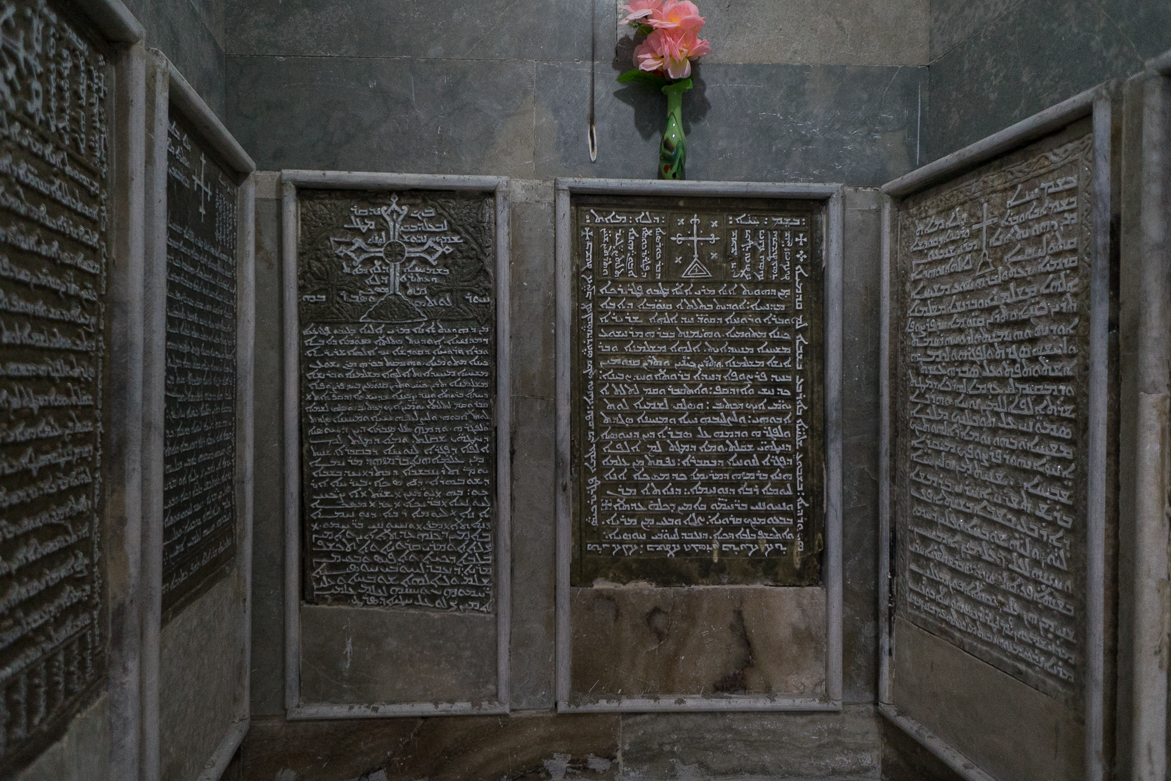

First buried in the martyrion of the original monastery, which has been moved because of earthquakes, Mar Rabban Hormizd has been transferred to the vault in the modern part of the monastery.

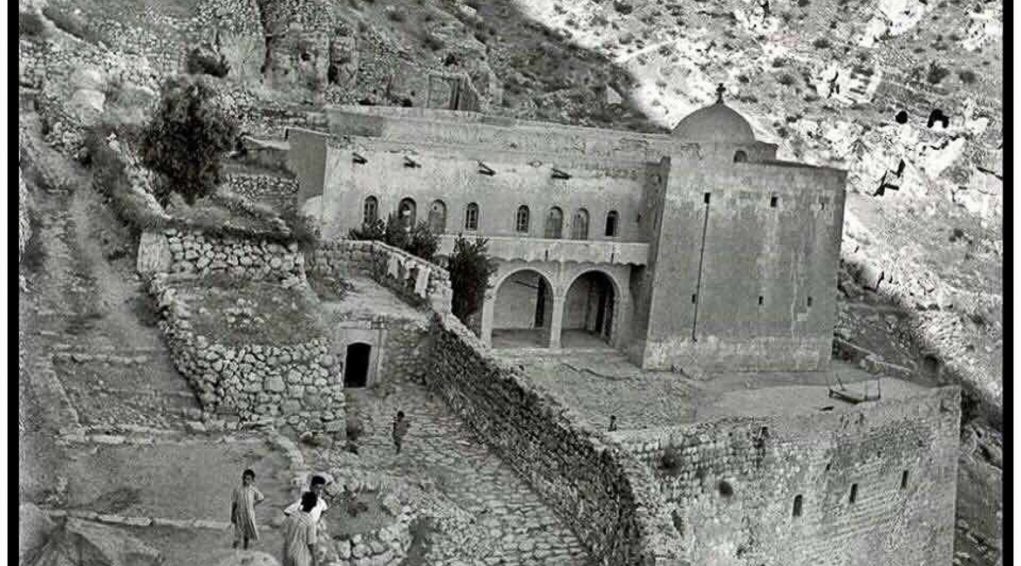

Caves and hermitages hewn out of rocks all over the mountain

The monastery’s site shows an intense monastic hermit life. Caves carved into the rocks are scattered all over the mountain around the monastery. Even nowadays, there are more than 40 cells. Some are obviously very difficult to access; others have been progressively integrated within the monastic buildings. The cells’ sizes vary from very small to bigger ones. In this site just like in other monasteries in eastern regions, the system of interconnected caves emphasizes the importance of ascetic life, and also the necessary resources used to keep them as safe as possible.

Never-ending invasions

Over several centuries of history, Mar Rabban Hormizd Monastery has not been spared by conquering armies, as with the Kurds from Hakkari (in modern-days south-eastern Turkey) who, in the 10th century plundered the region, its villages and monasteries. This led henceforth to the scattering of the Rabban Hormizd Monastery’s monks.

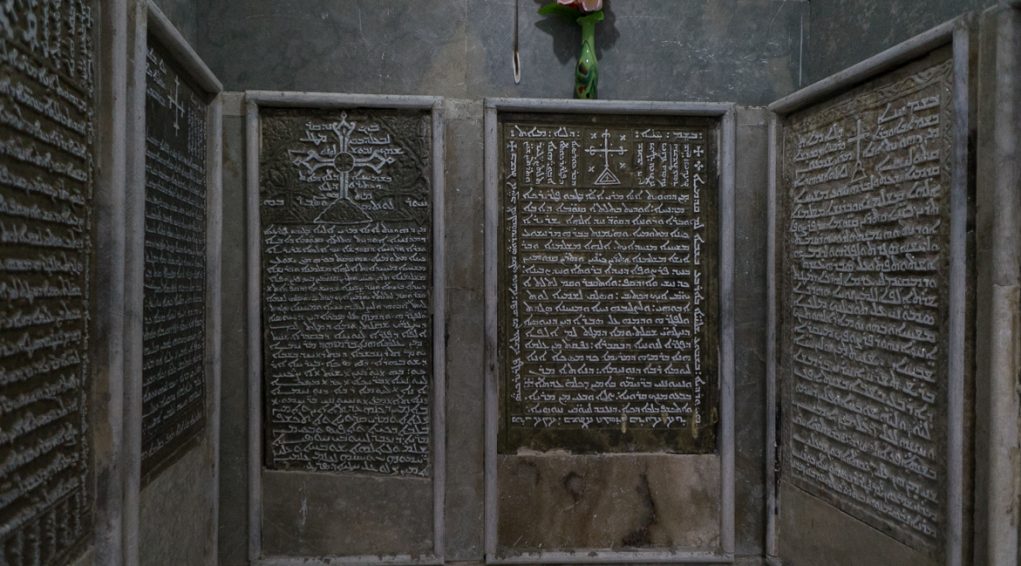

After persecution periods, came the time for revival periods. Thereby, a monk known as the “first known scribe of the monastery, monk and priest Daniel lived there in the 13th century. We owe him a gospel from 1208 and a New Testament from 1222, for which we cannot assert Fr Daniel wrote it himself, [but] which was written in Rabban Hormizd[1].”

During the 14th and 15th century, numbers of invaders overran the region, amongst others the Mongols and the conqueror Tamerlane, leading to plunders and desertions at the monastery.

Rabban Hormizd Monastery takes its historical importance also and above all from the political and theological conflict which tore apart the Roman Catholic Church and the Church of the East in the 16th century.

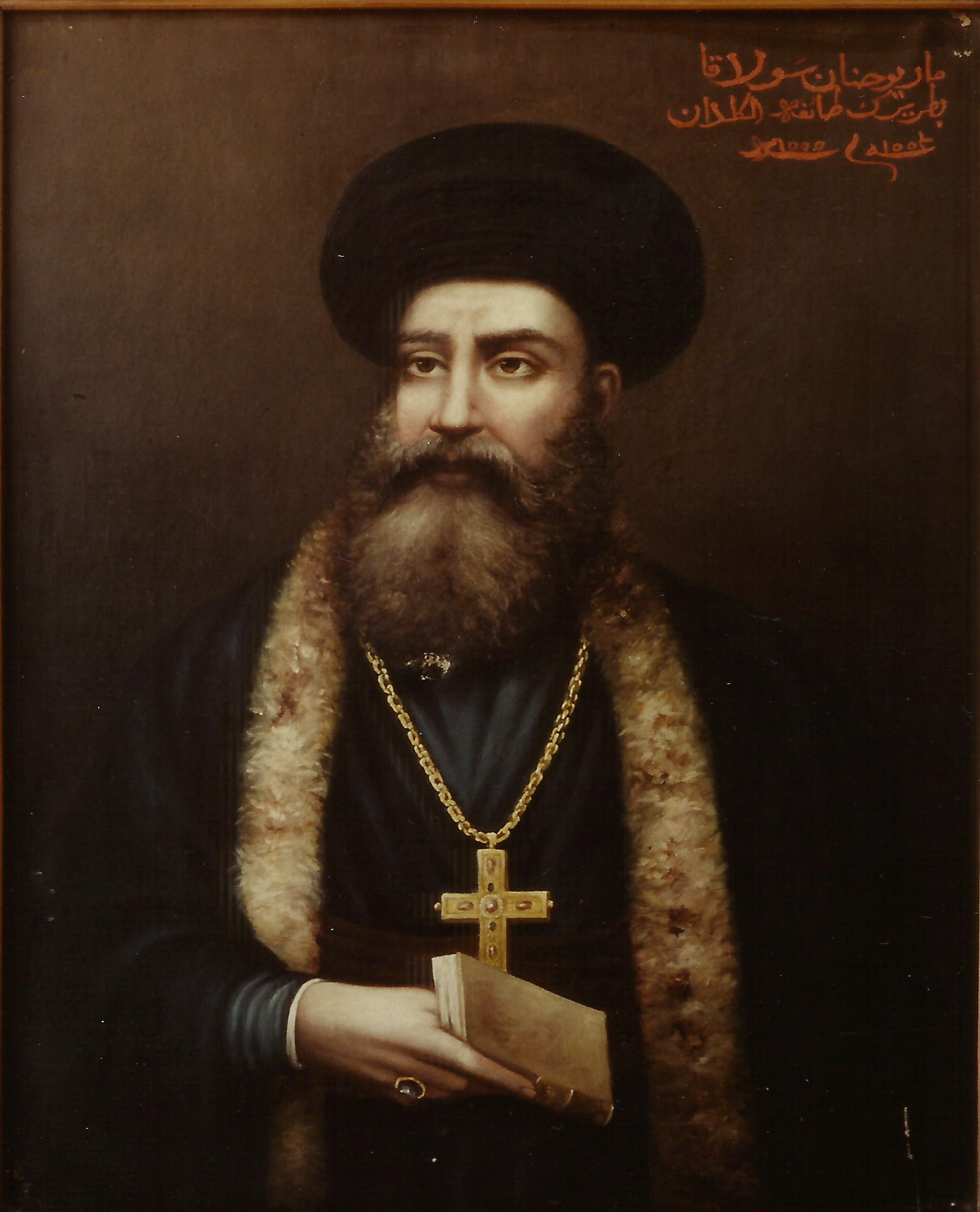

On April 9th 1553, Yohannan Sulāqa, abbot of Rabban Hormizd, was consecrated as the first Patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church by Pope Julius III. He had been sent to Rome by Nestorian bishops, who were contesting the Patriarchate of the Church of the East, and he received the pallium and the papal bull. Back to the Levant, the Chaldean

patriarch travelled to Constantinople and Diyarbakır, to meet with the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman 1st “the Magnifiscent” in search for legitimacy and recognition, which he obtained. The geopolitical situation needs to be taken into account about this event. Indeed, the Ottoman Empire was then at war with Persia, and this had consequences on the local churches, on their controversies and their political choices.

After having laid the foundations to structure the Chaldean Church, Yohannan Sulāqa was imprisoned by the Kurdish Pasha of Amadiya (extreme North of Iraq) and eventually executed by his henchmen, this crime being undoubtedly instigated by the Nestorian patriarchal clan of Bar Mama.

Rabban Hormizd Monastery became the residence of the Patriarchate and never stopped resisting to Kurdish plundering and persecutions, and also to earthquakes, which led to never-ending transformations and rebuildings.

The most important attack took place in April 1842. It ended up with “the monastery being totally plundered by Ismā’il Pacha, prince of ‘Amadiya. Books were torn up and burnt, monks were imprisoned in a cell and tortured, and then the abbot and twelve monks were dragged after the troops. After several months of torture, the abbot and another monk, Father Moses, died in Amadiya’s jails. When Badger [George Percy Badger, Anglican missionary and orientalist] got there, one year after, there were 39 monks left[1].”

In 1850, similar actions were repeated, leading – in addition to plundering – to the loss of more than a thousand valued manuscripts, that had however been “put away for safe-keeping in a small building down in the valley [but] which got flooded away by streams, next February [1851] [2].”

Over centuries, Rabban Hormizd Monastery became the most important see for the Patriarchate of the Church of the East, before becoming the see of the Chaldean Church. The cemetery itself can symbolize the Eastern religious and geopolitical situation.

[1] In Assyrie Chrétienne, Jean-Maurice Fiey

[2] In Assyrie Chrétienne, vol.II, page 547, Jean-Maurice Fiey, Imprimerie Catholique de Beyrouth.

[3] Id.

Physical description

Besides the vault of its saint founder, the monastery hosts a large number of tombs of Nestorian monks, abbots and patriarchs, as well as Chaldean monks, abbots and patriarchs. They can be found in different churches of the monastery, and especially in the Trinity Church, the most ancient, in the two-levelled new church, dedicated to the archangels Michael and Gabriel as well as to the Evangelists, and finally to the lower church.

From one monastery to the other

The never-ending outrages faced by generations of monks in this site (criminal ravages, earthquakes…) convinced the Chaldean patriarch Joseph VI Audo (1847-1878) to build a new monastery at the foot of the mountain, at the gates of Alqosh, at seeing distance from one another. The monastery of Our Lady of the Seeds was completed in 1858. Incidentally, the patriarch Joseph VI Audo (1847-1878) is buried in this new monastery. Easier to access, more modern, better adapted to the needs of pilgrims and visitors, Our Lady of the Seeds hosted one of the most important Chaldean library, created with manuscripts that had been saved from Rabban Hormizd Monastery and expanded gradually from that date.

News

Recently, the military pressure by Isis and the risk of invasion, with attackers just a few kilometres away from Alqosh, forced the Chaldean authorities to take protection measures for both people and heritage.

Monument's gallery

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute