The Ezdin Mîr Chamsani mausoleum in Shexka

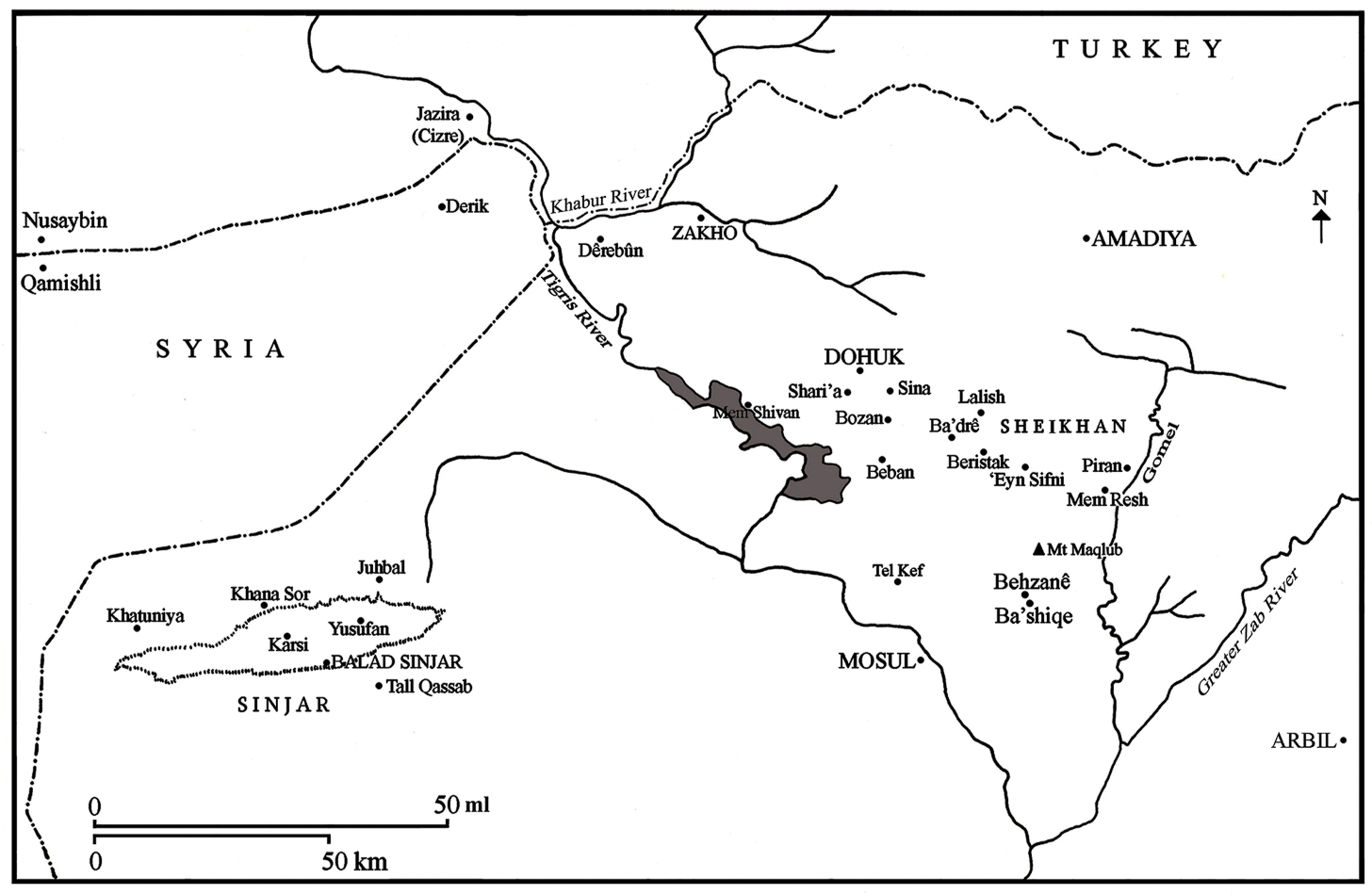

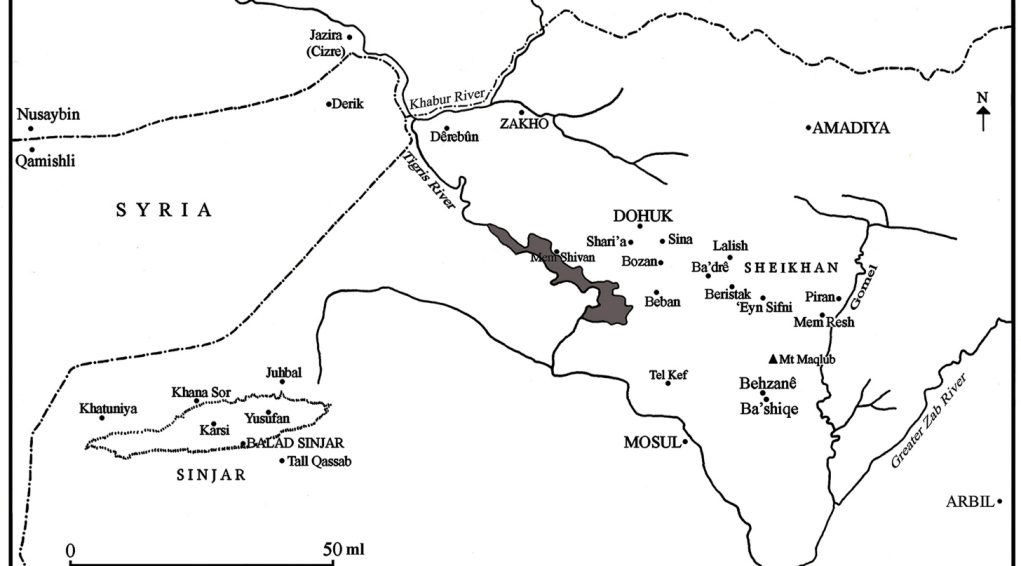

The Yazidi Ezdin Mîr Chamsani mausoleum in Shexka is located at 36°46’5.91″N 43°26’52.81″E and 591 metres altitude, on a hill at the entrance to the city 15 km from the Yazidi spiritual centre of Lalish.

The Ezdin Mîr Chamsani mausoleum is situated in the Yazidi cemetery of Shexka, at the summit of a green hill which offers 360° views of the surrounding agricultural land. The mausoleum’s architecture is characteristic of Yazidi tradition. In 2018, Shexka and the adjoining villages of Kersav and Khorza, were inhabited by 400 families. After the ISIS offensive in the Nineveh plain, the Shexka agglomeration swelled to 700 families.

The Yazidi mausoleum Ezdin Mîr Chamsani in Shexka June 2018 © Pascal Maguesyan / MESOPOTAMIA

About this file

The content of this file has been drafted by Dr. Birgül Açıkyıldız-Şengül, art historian, specialised in Yazidi heritage and culture. Dr. Birgül Açıkyıldız-Şengül is an associate researcher at the University Paul Valéry Montpellier III and the IFEA Istanbul, and is the author of a doctoral thesis: “Yazidi heritage: Funeral architecture and sculptures in Iraq, Turkey and Armenia” presented in 2006 at the University Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne (department of Islamic art and archaeology). This thesis contains a documented inventory of 88 monuments (sanctuaries, mausoleums, baptistries, oratories, caravanserai, bridges and caves) and 60 funeral sculptures (in the shape of horses, rams, sheep or lions) in northern Iraq, Turkey and Armenia. Thesis published by I.B.Tauris (London, New York), 2010. The text has been enriched with the observations and interviews of the Mesopotamia team (Pascal Maguesyan, Shahad al Khouri, Sibylle Delaître (KTO)) with support from Mero Khudeada.

Location

The Yazidi Ezdin Mîr Chamsani mausoleum in Shexka is located in 36°46’5.91″N 43°26’52.81″E and 591 metres altitude.

Located 50 km east of the eastern bank of the Mosul dam on the Tigris and 15 km to the east of the Yazidi spiritual centre of Lalish, the Yazidi Ezdin Mîr Chamsani mausoleum in Shexka is in the north of the Nineveh province, less than 10 km from the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan.

In Shexka and throughout this border region, the inhabitants speak Arabic and Kurdish.

About the Yazidi in Iraq

Mainly settled in the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan and the Nineveh plain, their geographic birthplace, there are also Yazidi in Turkey, Syria, and the Caucasus in particular in Armenia and Georgia. Generally considered as non-Islamic Kurds, which is at the very a least a simplistic if not inaccurate statement given their mythological origins, often demonised due to their religious practices, the Yazidi are a community whose historical origins and number are difficult to estimate.

Marginalised to the extreme in Iraq under various regimes, their existence was practically denied. Prior to 2003, Baghdad officially only recognised a few thousand whereas the reality was no doubt closer to hundreds of thousands.

The conditions for an attempted genocide were already in place even before the ISIS jihadis started to massacre and kidnap Yazidi in the Sinjar mountains and province of Nineveh in August 2014.

Although the Iraqi forces and the coalition of resistance groups took back Sinjar in November 2015, the majority of the 500,000 – 600,000 Iraqi Yazidi are still displaced. The persecution they have suffered makes them fear for the future despite the constitutional guarantees afforded to them in 2005.

Enracinement territorial du yézidisme

Yazidism was founded in a mountainous territory where its inhabitants were protected by the slopes, peaks and caves. Considered sacred by the Yazidi, this territory roughly divides into two distinct regions, east and west of the Tigris, the key Mesopotamian river. To the west is Sinjar: the city, surrounding villages and the mountain range. To the east is the spiritual centre of Lalish, and the key sectors of Shekhan, Bozan, Bashiqa and Bahzani. The vast majority of the Yazidi population (including clergy) are from these regions although there are some scattered Yazidi communities outside of these areas.

For centuries, the Yazidi have preserved their customs and traditions in this region, this territory. This preservation of the past was cruelly undermined to the west of the Tigris in the Sinjar region by the devastating ISIS offensive in August 2014. The extent of the destruction and severity of the genocidal crimes committed severely weakened the Yazidi communities in the Sinjar mountains who previously formed the core of the Iraqi Yazidi population.

Territory, history and heritage

It is in this region, either side of the Tigris, that the Yazidi were able to preserve and develop the characteristic architectural features of their religious buildings which are the main places of worship for the Yazidi faithful.

These buildings are mostly dedicated to the first disciples of the 12th century Yazidi reformer, Sheikh ‘Adî, members of the Chamsani families and families such as Hasan Maman, Memê Rech and Cerwan, as well as the community’s first religious leaders, descendants of Sheikh ‘Adî (members of the Adani family) and certain important Sufi mystics who influenced Sheikh ‘Adî’s teachings, namely Abd al-Qadîr al-Jilani, al-Hallaj et Qedib al-Ban (Qadî Bilban).

However, it would be wrong to conclude that Yazidism is a medieval religion. The paucity of the theological and historical sources available is compensated for by the ancient tradition and mythology which are omnipresent and constantly developing. The Yazidi consider Noah to be one of their most ancient and most illustrious patriarchs. They even claim that he lived in Iraqi Mesopotamia, in Ain Sifni (Shekhan) where he built his ark. The Yazidi historians claim that “the Yazidi religion is very ancient. It goes back to 3,500 years BC.”[1]

The Yazidi have a wide diversity of places of worship and prayer, including cemeteries, mausoleums (mazar) some of which are larger than others (khas / mêr), fire oratories (nîshan), the houses of Sheikhor Pîr, trees, bushes, olive groves, bridges, arches, caves, sacred stones (kevir), springs etc. These monuments, structure and sites dedicated to the Yazidi “saints” constitute a large proportion of the cultural setting of the Yazidi communities and are the tangible, physical manifestation of the Yazidi belief system as a whole.

There is however, one fundamental place which all Yazidi turn to, including the diaspora: the Lalish valley in Iraqi Kurdistan. It is the most sacred place in Yazidism. It is the location of the sanctuary of Sheikh ‘Adî, the great reformer of Yazidism in the 12th century. This valley, its mausoleums and its environment are the centre of gravity of Yazidi spiritual life.

The Yazidi buildings were built at different times. The lack of inscriptions and historical sources make it difficult to date them accurately. The poor quality of some of the more recent restorations makes this analysis even more complex. Furthermore, there do not seem to be specific architectural styles associated with specific periods of Yazidi history which could help to date these buildings. In addition, the same style, derived from a specific model has been used at several times over the centuries and is still in vogue.

______

[1] Chamo Kassem, inspector of Yazidi schools, specialist in Yazidi religion and culture, Head of Culture and Media, at the Lalish Cultural and Social Centre in Dohuk-Nohadra.

Fragments of Yazidi spirituality and theology

Yazidism is a religion based on tradition and oral history that is both simple and complex at the same time. Simple, because it is not regulated by a constraining liturgy or dogma. Complex, because there is no fundamental theological document underpinning it such as the Torah, the Gospels or the Koran. The Yazidi have two sacred books: the book of revelation “Kitêb-i Cilvê “, and the black book “Mishefa Reş”.

Yazidism is a strictly community-based religion (national). One is born Yazidi, you cannot become Yazidi. There is no evangelizing, inculturation or proselytizing. That said, Yazidism is not sectarian. Quite the opposite, altruism is considered to be a cardinal virtue, a spiritual and theological foundation. Any researchers interested in studying Yazidism are therefore warmly welcomed by the community and its clergy.[1]

Yazidism is a monotheism. God is singular and unique. He is the creator of the cosmos and of life. In this, Yazidism shares the same belief as the three main monotheist religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. As well as Zoroastrianism.[2]

God is light. He is like the sun which shines on the Earth. That is why the Yazidi systematically face the sun to pray. This is something Yazidism shares with Mesopotamian and Persian Zoroastrianism.

God is good, infinitely good. This is why the Yazidi encourage altruism and always pray firstly for the world and then for themselves.

God is everything and is everywhere. Yazidism is physically and spiritually one with the whole of Creation: cosmic, human, animal, vegetal, and mineral. That is why olive trees whose oil is used for the sacred fire are considered sacred by the Yazidi. Similarly, the angel peacock (tawûsê melek) is the most important of the seven angels (melek) which represent God on earth.

Yazidism believes in the judgement of souls and the last judgement. However, it differs from Christianity in its belief in reincarnation. The dead are buried. Their souls are judged according to the good and evil they have done. Pure souls become beings of light. Impure souls are reincarnated in devalued or bellicose human or animal forms.

________

[1] « Jean-Paul Roux, who passed away in 2009, former CNRS researcher and head of the Islamic art section of the École du Louvre, considered Yazidism as “a standout religion, an obvious syncretism of popular tradition and reminiscences of the dogma of the major religions’’. La Croix, Claire Lesegretain, 26 April 2010.

[2]Born in Persia, founded by Zarathustra (Zoroaster) in the first millenium Before Christ, Zoroastrianism is monotheist and recognises Ahura Mazdâ as the only God. In this sense Zoroastrianism is fundamentally different from the Mazdaism it is derived from. Mazdaism is polytheist, considering Ahura Mazdâ as the main, but not the only, God. This Persian religion spread as far as India in the form of Vedism.

Yazidi worship

Yazidi worship is not governed by a strict liturgy but constitutes a set of traditional rites and votive practices passed on orally from generation to generation.

The Yazidi generally pray individually, but also gather together as a community at their temples and sanctuaries to listen to qawals, who are both musicians and the gatekeepers and guardians of the Yazidi religion, whose knowledge and practices are passed on from father to son.

The daily prayer, facing the sun, the light of God (Khoda), is not an obligation nor is it required to show you are a “good” Yazidi. However, pious, elderly people pray regularly, up to five times a day.

Kissing sacred places and the hands of saintly figures, offering gifts to consecrated persons, sacrificing animals, knotting and unknotting fabric on wish trees, are all signs of respect and devotion.

Wednesday is the most important day in the week. It is like Sunday for Christians, Saturday for Jews and Friday for Muslims. The main weekly services during which the Yazidi monks light the sacred fire in the mausoleums are held on Wednesdays.

Four major annual festivals are held during the Yazidi religious year. The first is the New Year (ser sal) celebrated on the first Wednesday of the month of April. This festival symbolises the creation of life out of the initial chaos and the coming of tawûsê melek. Eggs, a symbol of the original lifeless earth, are boiled and dyed as part of the celebrations. Some of these eggs are smashed above the doors of houses and mausoleums, mixed in with small red flowers.

Another major annual festival is the Spring festival (towaf), which is held on a date between 12th – 20th April. Finally, the pilgrimage to the tomb of Sheikh Adî, in the Lalish sanctuary (djamaiya) takes place on 6th October.

The mausoleum with a conical dome: characteristic Yazidi architecture

Mausoleums with a conical, striped dome are emblematic of Yazidi sacred art. Extremely sober in terms of its architecture and decoration, this type of building is built on a cube structure which contains the tomb or cenotaph, covered by a slab with a drum, above which stands a conical dome composed of multiple crests. This vault symbolises the sun’s rays which light up the earth and humanity.

The pinnacle of the dome is systematically fitted with a bronze spire formed of one or more spheres, mounted with a ring, a crescent moon, and a celestial body or hand, around which swathes of coloured fabric are knotted. The spire represents the cosmos, the planets, the sun and the stars created by God. The coloured fabrics represented the colours of the rainbow. [1]

The interior of a Yazidi mausoleum is often composed of a separate chamber containing a sarcophagus covered in silk fabrics. There are also often several niches carved into the walls to burn incense and light the sacred fire. These often also contain knotted fabrics placed there by pilgrims making wishes.

The sacred space in any Yazidi mausoleum includes the slab in front and around it. That is why any visitor or pilgrim must remove their shoes.

_______

[1]This interpretation can vary from one community to another.

Yazidi demographics in Shexka

In 2018, Shexka and the adjoining villages of Kersav and Khorza, were inhabited by 400 families. [1]

After the ISIS offensive in the Nineveh plain, the Shexka agglomeration swelled to 700 families.

There are only a handful of families of shepherds living in the other ancient villages in the sector, Kersav and Khorz.

Shexka was evacuated on 7th August 2014 for fear that the jihadi fighters who were just 12 km away would take the village. It was two months before the danger passed and the villagers were able to return to Shexka.

There are also 200 Yazidi families from the Sinjar, devastated by ISIS and bombing raids, living in Shexka.

Another 150 families from Bashiqa and Bahzani who sought temporary refuge in Shexka have returned to their homes.

_______

[1]Data collected by Mesopotamia’s representatives in Shexka, on 6th June 2018.

The Yazidi mausoleums in the Shexka agglomeration

There are two mausoleums in Shexka, a mausoleum in Kersav and two mausoleums in Khorza. Each of these two villages has a cemetery for infant children aged under 7 years old. The other Yazidi deceased are buried in Shexka and Bozan.

The Yazidi mausoleum Ezdin Mîr Chamsani in Shexka

A contemporary of Sheikh Adî, the great reformer of the Yazidi religion, Ezdin Mîr Chamsani was one of his companions.

Local history recounts that Ezdin Mîr Chamsani lived in Shexka 900 years ago. His mausoleum was built at the same time and has since been regularly rebuilt over the centuries.

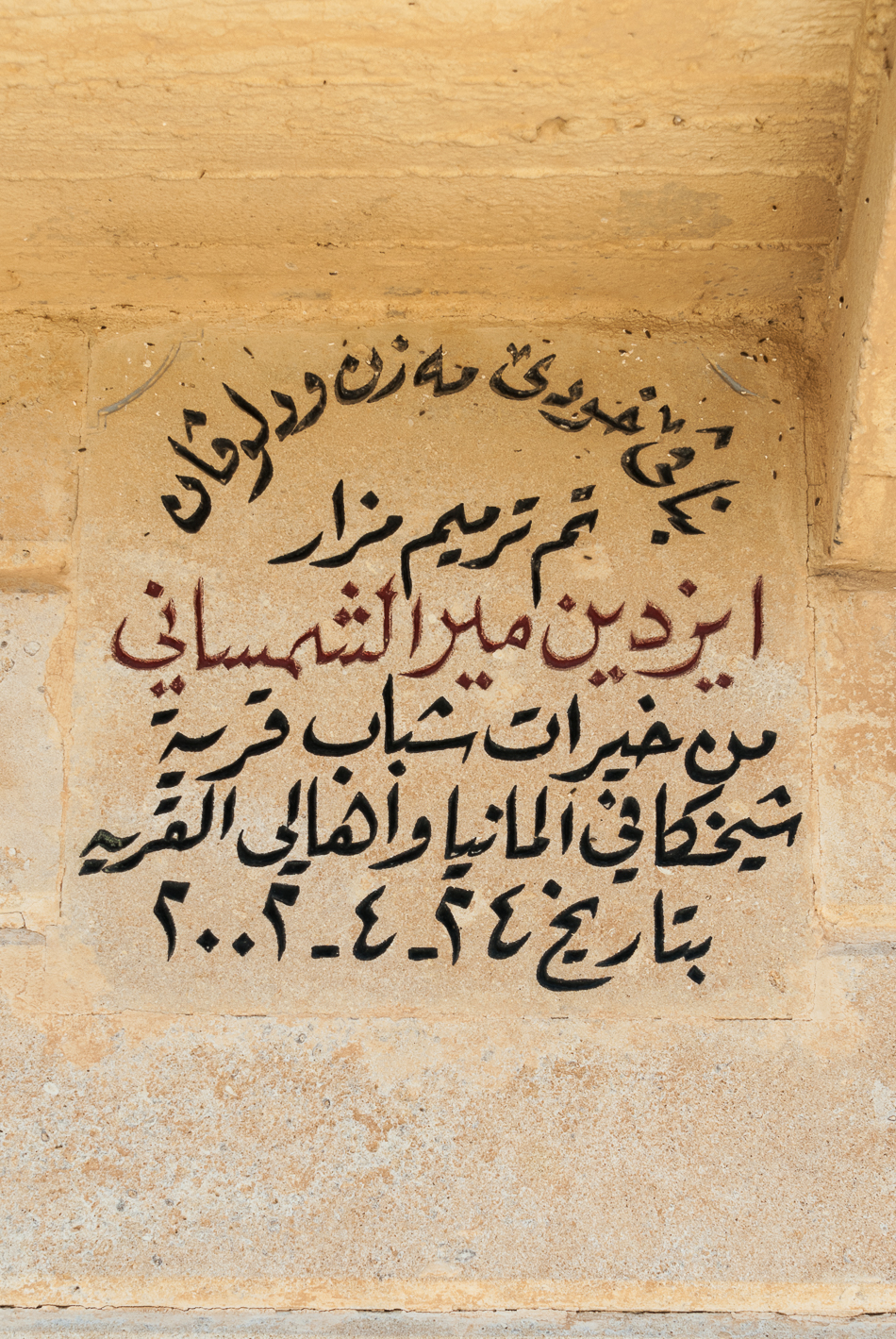

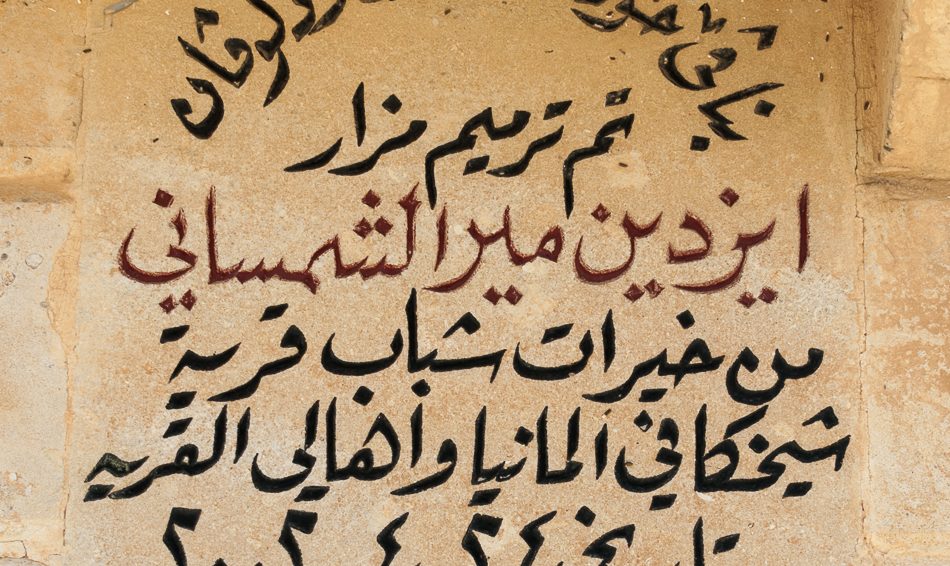

On the facade of the mausoleum is a dedication inscribed on 24th April 2004 at the time of the most recent restoration which was by the villagers of Shexka with the help and support of Yazidi from Shexka emigrated to Germany

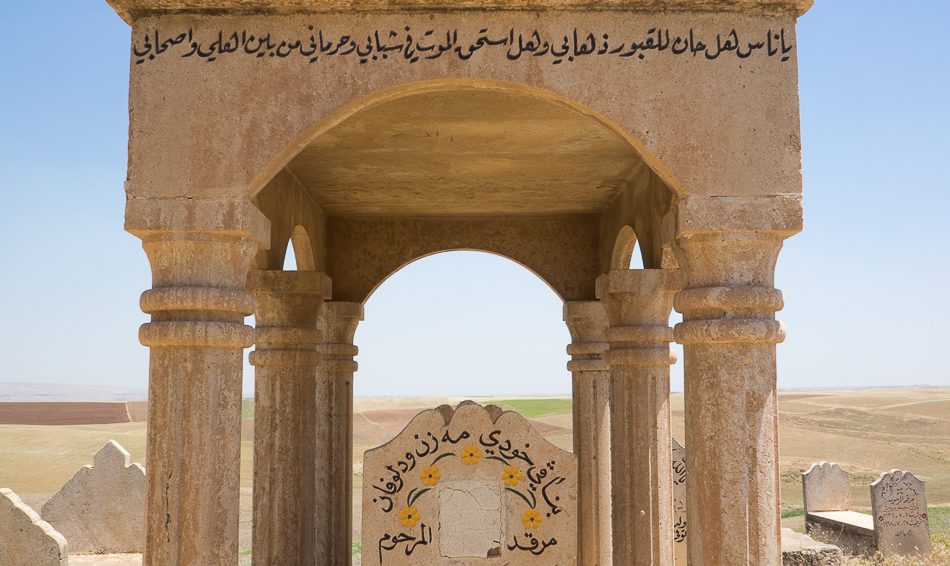

The Ezdin Mîr Chamsani mausoleum is situated in the Yazidi cemetery of Shexka, at the summit of a green hill which offers 360° views of the surrounding agricultural land.

The Yazidi tombs in the cemetery are very diverse. Some are extremely modest, others much more elaborate. These tombs date from different periods both ancient and modern.

The architecture of the Ezdin Mîr Chamsani mausoleum in Shexka is symbolic of Yazidi tradition, although the use of reinforced concrete attests to the modernity of its reconstruction.

The sacred space of the mausoleum starts on the 2-metre wide slab built in front of the entrance to the building. That is why any visitor or pilgrim must remove their shoes.

The Ezdin Mîr Chamsani mausoleum is a square building which reaches 2.5 metres high, excluding the drum and the dome.

A double-leaf metal door provides access to the monument. Each leaf is decorated with a peacock made of painted wrought iron. In the Yazidi belief system the peacock (tawus) is one of the seven angels (melek). It is also, and above all, the highest angel to whom God delegated his powers on earth. The peacock angel, Tawus Melek, is the manifestation of the creator.

The slab in the funeral chamber supports in one corner a three-level drum, first square, then octagonal, then circular, which is about 1.5 metres high, above which stands a conical radiating dome. These concrete rays are a symbolic representation of the sun’s rays which illuminate the earth and humanity.

The pinnacle of the dome is mounted with a spire with two spheres and a ring to which coloured fabrics are attached. These two spheres and the ring represent the cosmos, the planets, the sun and the stars created by God, and the colours of the fabrics are those of the rainbow. [1]

Inside the mausoleum, the funeral chamber of Ezdin Mîr Chamsani is fitted with a low window on the sill of which is a saucer full of olive oil which allows the clergy to light the sacred fire using small imbibed cotton wicks.

On the inside wall, next to the funeral chamber, the knotted fabrics are used by pilgrims to make wishes.

_______

[1]This interpretation may vary from one community to another, or from one person to another, because Yazidism is mainly passed on through oral history so the interpretations are sometimes different although usually convergent.

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute