The cathedral of the Sacred Heart in the archdiocese of Kirkuk

The Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in the archdiocese of Kirkuk is located at 35°27’39.69″N 44°22’46.47″E and 339 metres altitude.

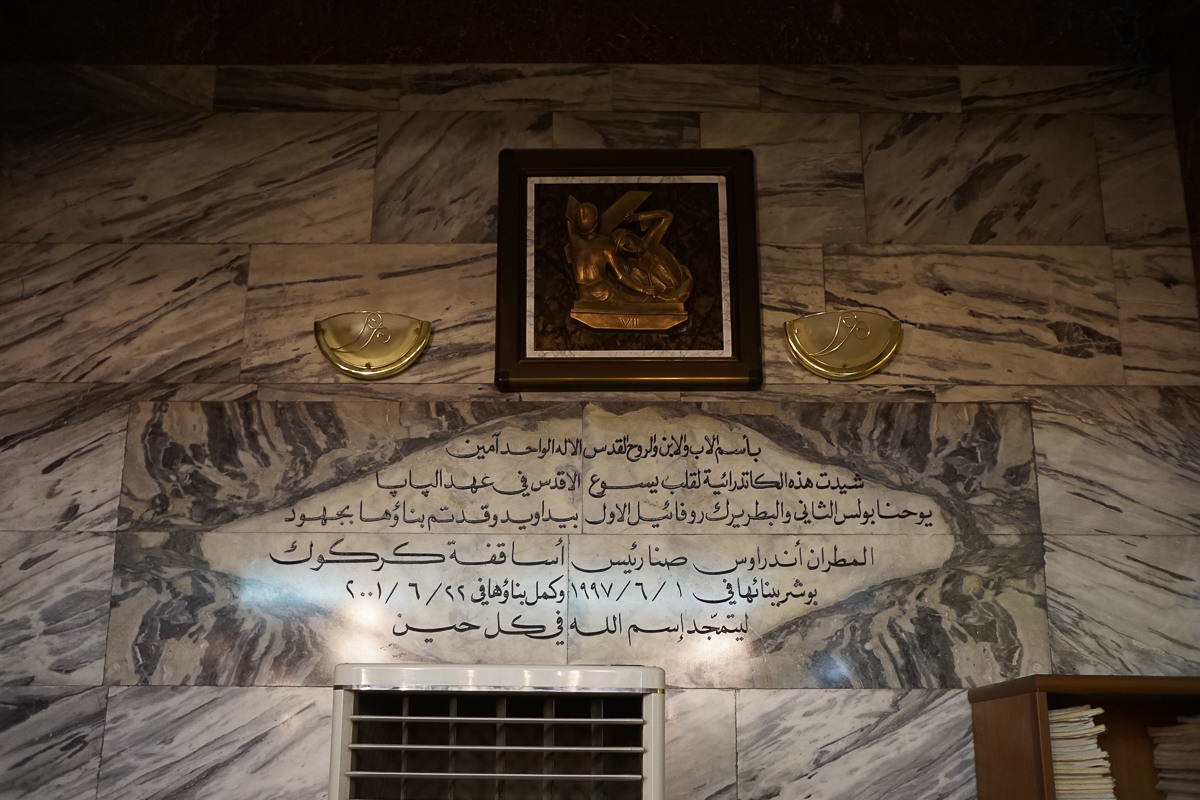

The building work on the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in the archdiocese of Kirkuk started on 1st June 1997 and ended on 22nd June 2001. Its construction made it possible to relocate local Christian life to a modern district of the city.

The cathedral was named after the cult of the Sacred Heart inspired by the French 17th century mystic Saint Marguerite Marie Alacoque.

The cathedral borrows from various styles which gives it its own unique identity: with a neo-classical facade, neo-Babylonian decorative crenels and merlons on the roof and neo-traditional bell-towers.

The baptistery of the cathedral of the Sacred Heart is not located inside the perimeter of the building but in a small isolated chapel adjacent to the archdiocese. It is known as the chapel of the martyrs (bēt sahdē, in Syriac), the worship of which is ancient and primordial in Mesopotamian churches.

Pic : The Chaldean Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in Kirkuk February 2018 © Pascal Maguesyan / MESOPOTAMIA

Location

The Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in the archdiocese of Kirkuk is located at 35°27’39.69″N 44°22’46.47″E and 339 metres altitude, in a relatively recent district.

Kirkuk, city and provincial capital, located to the east of the Little Zab. The Khasa river, a seasonal tributary of the Tigris, passes through the east side of the city. Situated to the north-east of Iraq, the region where the modern-day Kirkuk is located was known in ancient history as Bét Garmaï, formerly inhabited by the Garameans, possibly originating from “a Persian tribe which came to the region prior to Islam”[1], but also possibly Ninevites and Chaldeans who spoke “Aramean certainly.”[2]

_______

[1] [1] In Assyrie Chrétienne, vol.III, p. 15, Jean-Maurice Fiey, Imprimerie catholique, Beirut, 1968.

[2] Id. p.16

Demographics and geopolitics

The vast majority of the 1.2 million strong population of Kirkuk are Kurds. The rest of the population is made up of Turkmen (Shia and Sunni), Arabs (Sunni) and Christians (mainly Chaldean and a very small proportion of Armenians). There also used to be a Jewish community in the city, which no longer exists. In 2018, there are thought to have been 5,000 Chaldean Christians in Kirkuk out of the 7,000 across the whole diocese.[1]

In 1838, there were only 300 Chaldeans for 15,000 inhabitants in Kirkuk. At the end of the 19th century, there were 800 Chaldeans for 30,000 inhabitants.[2] This Chaldean Christian community, although modest, was 5-time larger in percentage terms than it is in 2018.

A major oil-producing hub in the north of Iraq, sectarian tensions flared in Kirkuk at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries and were exacerbated in the 1990s by the first Gulf war and the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003. Massoud Barzani, former President of the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan, laid claim to the city which was protected by Kurdish Peshmerga in June 2014 when the ISIS tried to take the city.

The referendum on the independence of Iraqi Kurdistan, which took place on 25th September 2017, included the province of Kirkuk, but by 16th October the Iraqi armed forces and associated paramilitary groups had retaken military and political control of Kirkuk.

________

[1] Source: Monsignor Yousif Thomas Mirkis, archbishop of Kirkuk.

[2] Source Michel Chevalier, in “Les Montagnards Chrétiens du Hakkari et du Kurdistan septentrional”, Université Paris-Sorbonne, 1985, cited by Monsignor Yousif Thomas Mirkis, archbishop of Kirkuk, in a personal memo.

Fragments of the Christian history of Bét Garmaï and Kirkuk

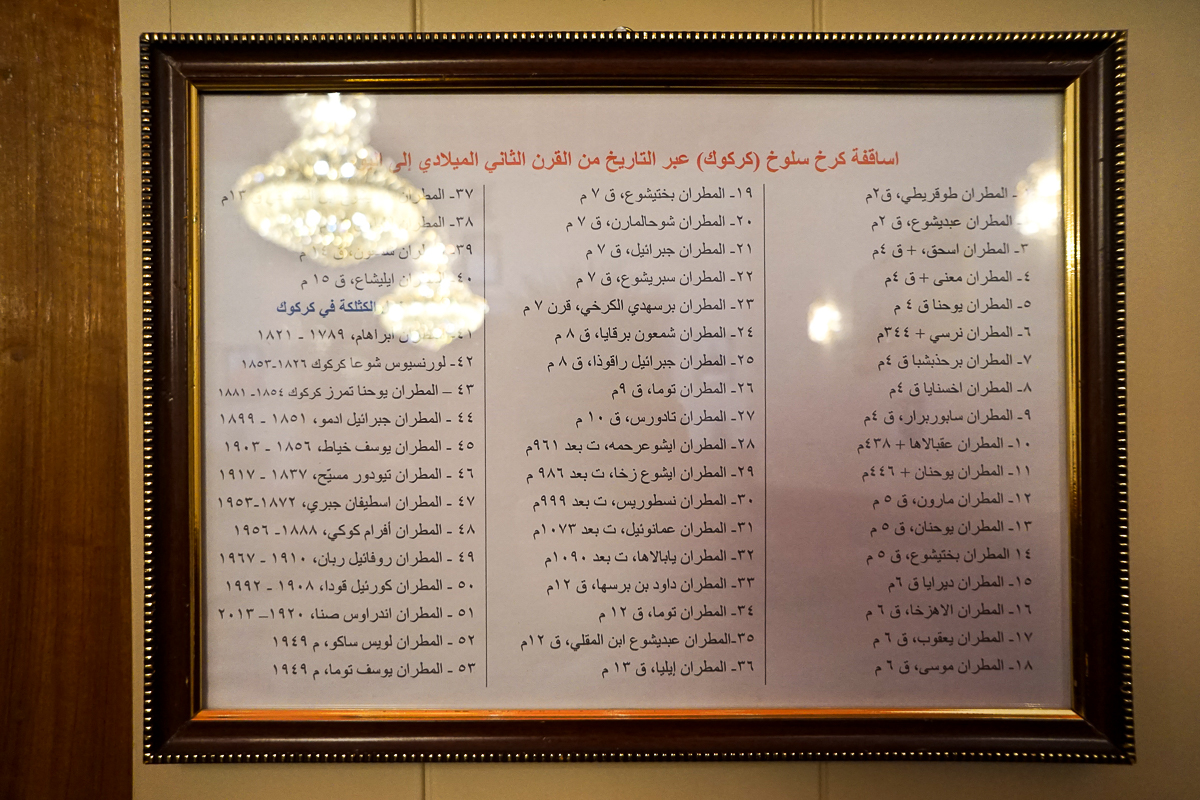

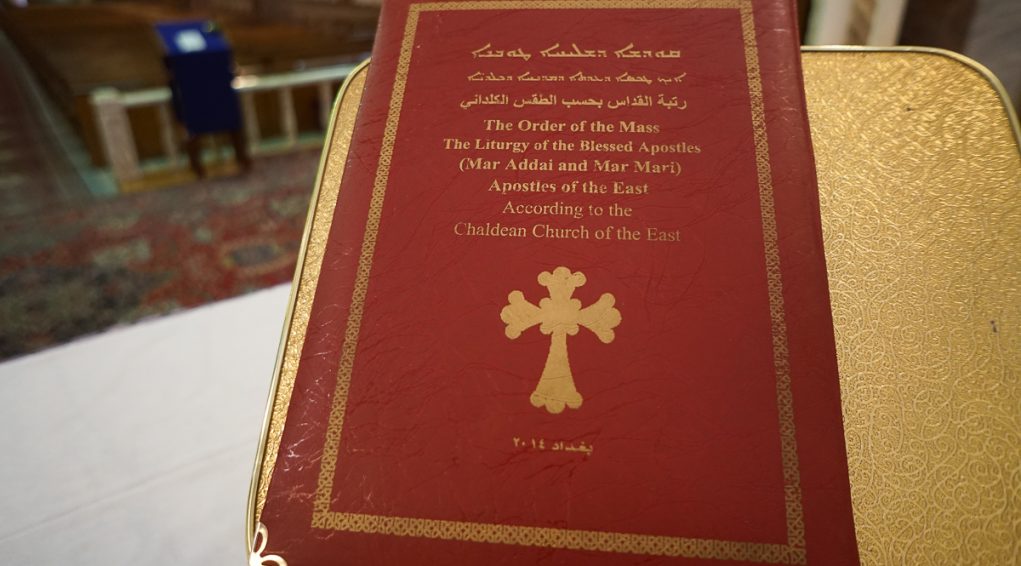

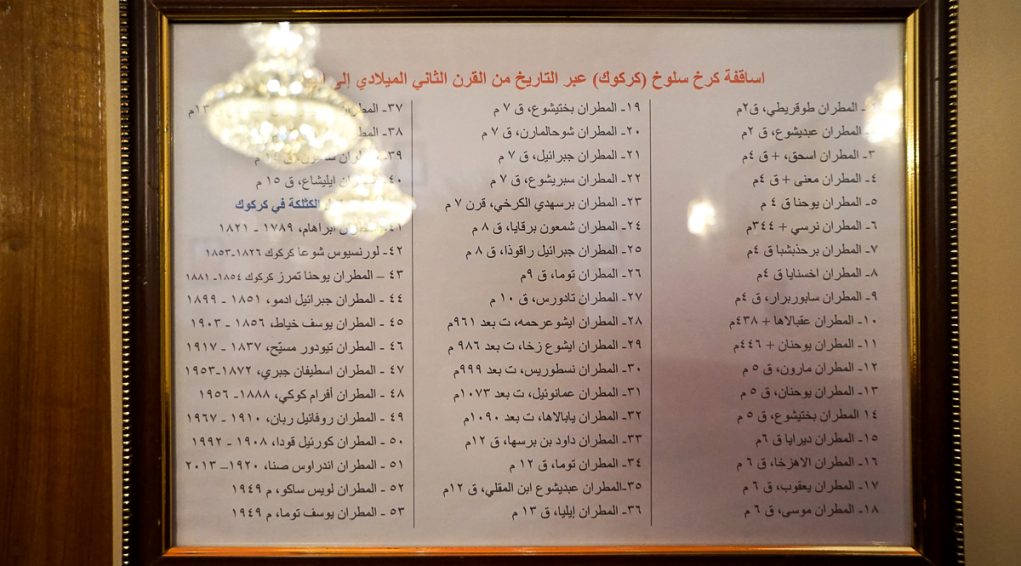

Christianity came very early on to Bét Garmaï, as part of the evangelisation of Mesopotamia by the apostle Saint Thomas and his disciples Addai and Mari. The tradition names the first known bishop of Kirkuk as Theocritus[1] Most likely originally from the Graeco-Roman world, he may well have sought refuge in Persia and dispensed his apostolate in Kirkuk at the very beginning of the 2nd century, between 117 and 138.[2]

In the History of Karka [3]“the most ancient Christian sanctuary in the city would be the church built on the site of the house of Joseph, the first convert of Mār Māri[4].”All traces have been lost of this sanctuary, which was not located inside the citadel of Kirkuk, but two kilometres away in Koria, today a district of the metropolis.

The Christian history of Kirkuk was marked by the persecution perpetuated by the Sassanid king Yazdegerd II, in 445, which caused “not only 12,000 deaths, but [also the loss of] the entire hierarchy.[5]” At war with the Eastern Roman Empire, converted to Christianity, the Persian king considered Christians to be enemies of the kingdom and stepped up the imposition of Zoroastrianism across the empire. Six years after the martyrdom of the Christians of Kirkuk, he committed his troops to fighting against the Armenians who he defeated in the Avarayr plain. In this case as in the precedent, Yazdegerd II not only failed to eliminate Christianity from the Persian Empire, but also started the cult of martyrs which is still today an essential part of Mesopotamian Christianity.

The church and cemetery of Tahmazgerd in Kirkuk still bear the signs of the persecution perpetrated by Yazdegerd II. After his death, the Christians of Kirkuk erected a large martyrion in around 470 and began a commemorative service to “perpetuate the memory of the triumph of the victims[6].” The Tahmazgerd site, located on a hill to the east of the citadel is now the most ancient Christian site visible in Kirkuk (see corresponding file). Each year, the Christians of Kirkuk commemorate the martyrs of Tahmazgerd on 25th September.

The Monophysite Christians (Syriac) of Bét Garmaï then had to fight against the intolerance of Barsaume, the Nestorian Metropolitan of Nisibe (Nusaybin), at the end of the 5th century, around 484/485. Those who refused to turn to Nestorianism, who resisted, were killed or forced to flee. Throughout the centuries and repeat crises, Nestorianism remained predominant in Bét Garmaï up until the constitution of the Chaldean church, united in Rome in 1553, which is said to have been popular with the Christians of Kirkuk very early on, although a fully-fledged local Chaldean church did not emerge until the 18th century.

_______

[1] Of Greek origin, Theocritus / Theocritos / Tocriti means “strength of God”

[2] Source: Monsignor Yousif Thomas Mirkis, archbishop of Kirkuk.

[3] Karka is the ancient Syriac name for modern-day Kirkuk

[4] [4] In Assyrie Chrétienne, vol.III, p. 49, Jean-Maurice Fiey, Imprimerie catholique, Beirut, 1968

[5] [5] In Assyrie Chrétienne, vol.III, p. 49, Jean-Maurice Fiey, Imprimerie catholique, Beirut, 1968

[6] Id.

History of the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in Kirkuk

The building work on the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in the archdiocese of Kirkuk started on 1st June 1997 and finished on 22nd June 2001, under the pontificate of Jean-Paul II and the patriarchate of Raphaël I Bidawid, at the time of Monsignor André Sana, archbishop of Kirkuk. An Arabic inscription inside the building, on the wall to the right of the entrance door testifies to this.

The construction of the cathedral made it possible to relocated local Christian life in a modern district of the city.

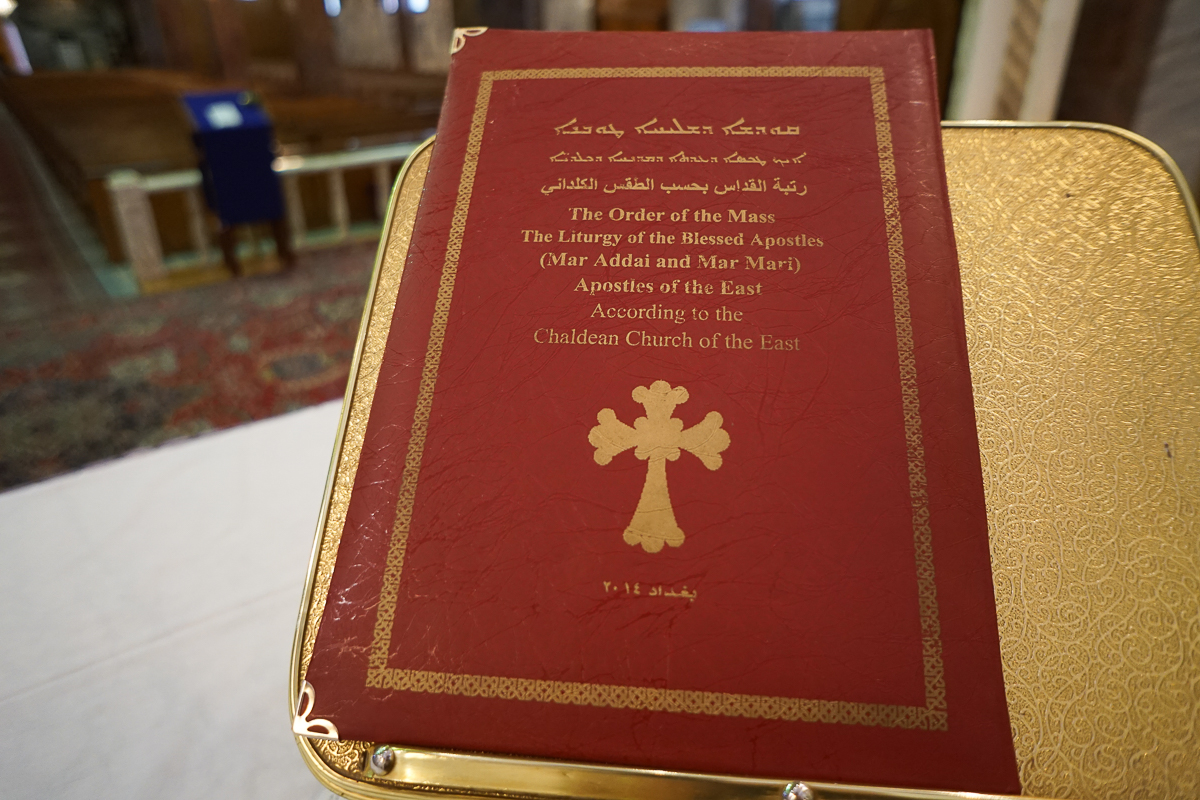

It was named after the cult of the Sacred Heart inspired by the French 17th century mystic Saint Marguerite Marie Alacoque. This form of worship was spread throughout Iraq by the Catholic missionaries, thus contributing to the “mystery of incarnation which is extremely important in the East.” [1]

________

[1] Source Monsignor Yousif Thomas Mirkis, archbishop of Kirkuk, 15th February 2018

Description of the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in Kirkuk

The Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in the archdiocese of Kirkuk borrows from various styles which gives it its own unique identity: with a neo-classical facade, neo-Babylonian decorative crenels and merlons on the roof and neo-traditional bell-towers and sacred interior architecture.

At the entrance, either side of the main, soberly decorated wooden door are two ionic crenelated columns which hold up the pediment decorated with crosses encircled with a repeat geometric pattern. On the corners of the facade are two bell-towers with a square base and mounted with lanterns.

Built from reinforced concrete, partially covered with stone facing on the exterior and covered with marble on the interior, the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in Kirkuk is a basilica church formed of a triple-nave hall supported with free-standing, square pillars. A tribune overlooks the entrance door. The slightly elevated sanctuary is open with a stone choir screen. A stone arch dominates the sacred space. It is decorated with an extract from the gospel in Arabic [1]and features four medallions representing the gospel writers. The high altar is made of marble with railings sculpted with angels. Behind this, on the wall of the apse is a large wooden cross of Saint Thomas. It is a cross as opposed to a crucifix, characteristic of the tradition of the Church of the East.

The side aisles of the church lead to two side altars, one dedicated to the Virgin Mary and the other to Saint Joseph.

_______

[1] Extract of the Gospel according to Saint Matthew, 11, 28-30: “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light.”

The baptistery

The baptistery of the cathedral of the Sacred Heart is not located inside the perimeter of the building but in a small isolated chapel adjacent to the archdiocese. It is known as the chapel of the martyrs (bēt sahdē, in Syriac), the worship of which is ancient and primordial in Mesopotamian churches.

The chapel is of no architectural interest. It is a small single nave structure, with carpeted floors, covered in decorative panels made of composite materials.

The sanctuary of the chapel of martyrs is decorated with two Byzantine mosaic icons, the first representing Christ, the second the Virgin and Child. A third contemporary painting by a German Priest, a symbolic reinterpretation of the Last Supper. It does not show the living Christ, but his hands with the stigmata of the crucifixion after his resurrection. The face of Christ appears as a shroud in the cup of wine. The people seated around him are not the apostles but the people of the world, and the table is laden with food and traditional dishes.

Testimony of Monsignor Yousif Thomas Mirkis, archbishop of Kirkuk and Suleymanieh.

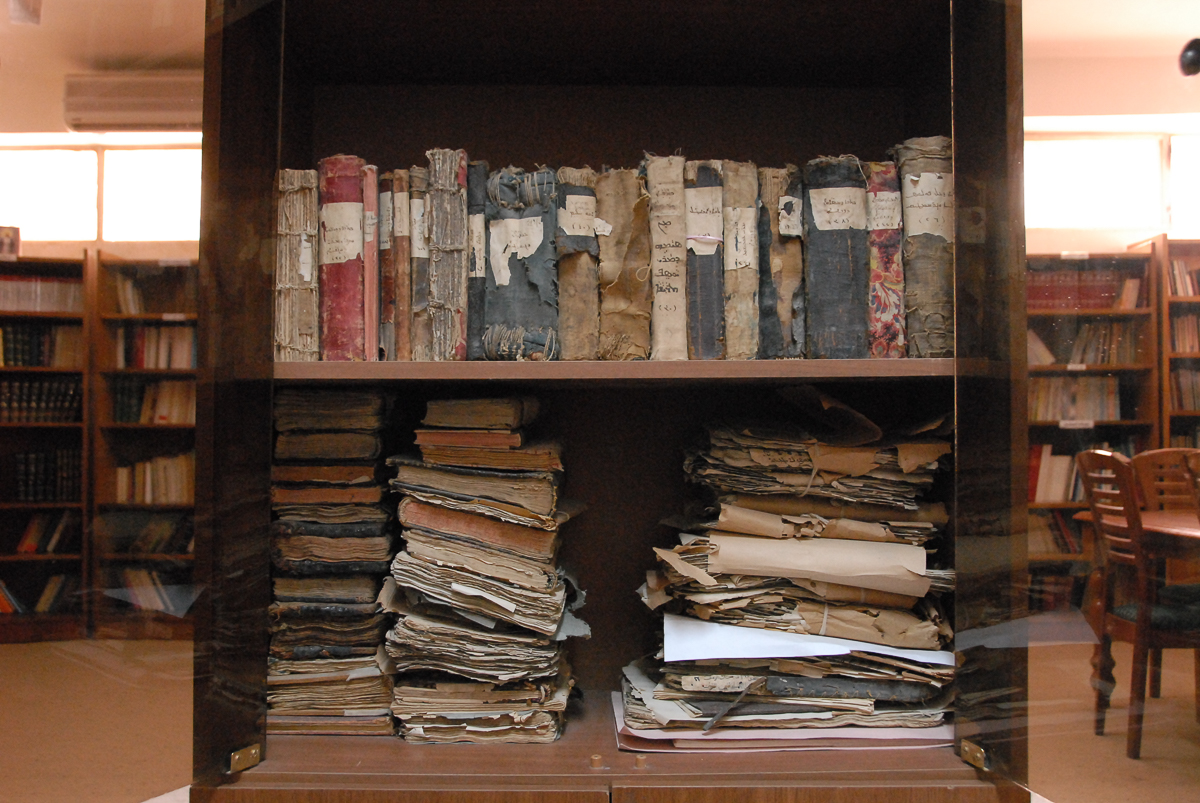

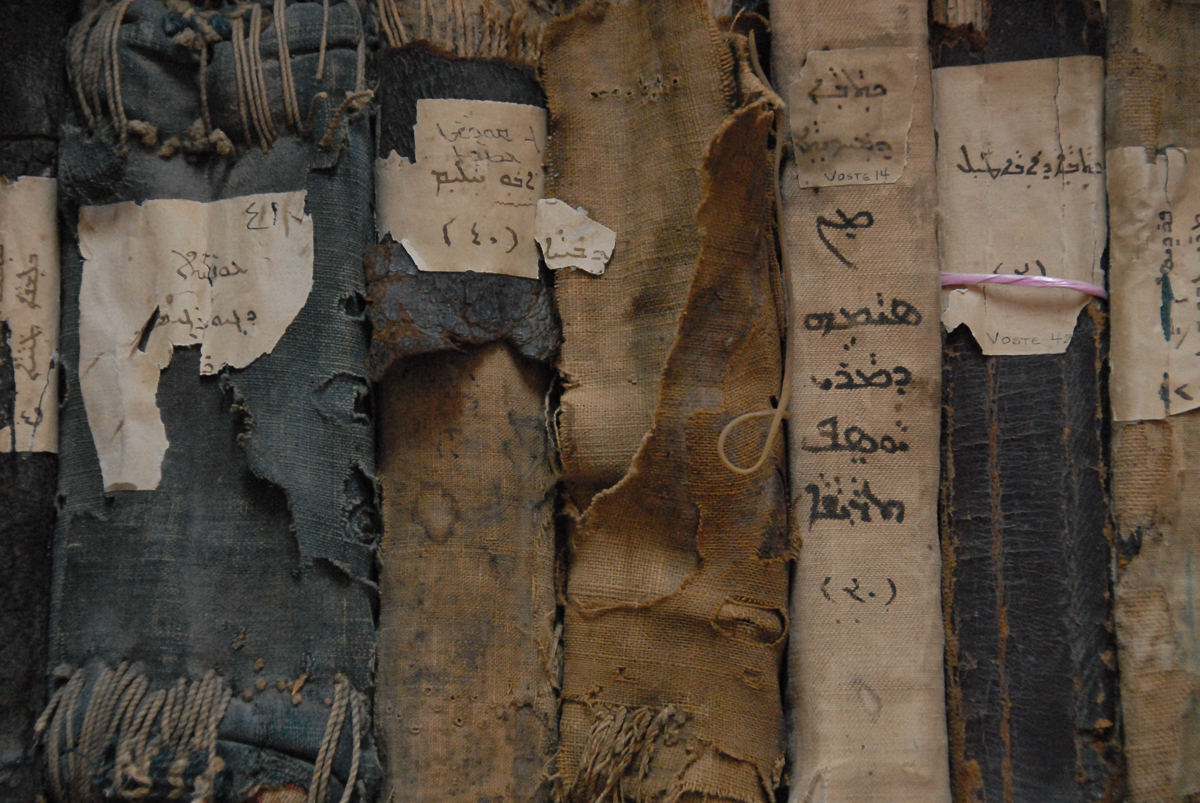

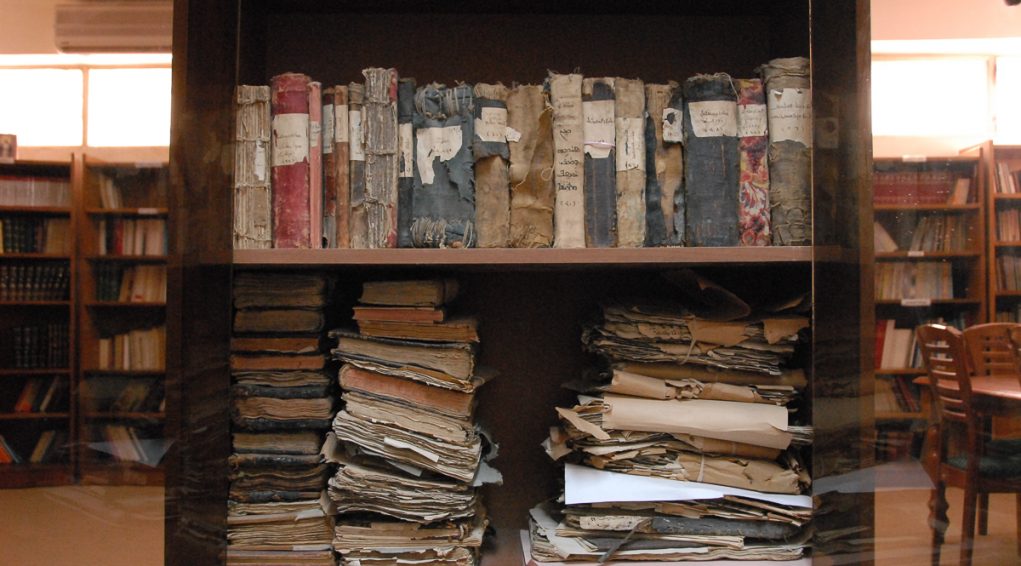

Monsignor Yousif Thomas Mirkis is the 53rd bishop of Kirkuk. The first, Theocritus, lived in the year 130. Born in Mosul on 21st June 1949, into a family originally from Zakho in the northernmost part of Iraq, Yousif Thomas Mirkis was educated at the ecumenical seminary of Saint John in Mosul. A Dominican, he studied theology, history, anthropology and linguistics in France. Former Editor-in-Chief of the renowned Arabic review “La Pensée Chrétienne”, in 2014 he was appointed archbishop of Kirkuk and Suleymanieh in 2014, taking over from Louis Raphaël Sako who became Patriarch of the Chaldean Church at this time. He had the remarkable works of Father Jean-Maurice Fiey translated into Arabic, in particular the three volumes of Christian Assyria his major historical work.

Below are his thoughts on spiritual and monumental heritage in Iraq:

Spiritual heritage: “Iraq’s Christian heritage cannot be separated from its religious history. Iraq is a sacred land. Jesus inherited the spiritual dynamic brought about by two Jewish diasporas: the first in the north in 721 BC, when large numbers of Jews came to live in the north of Iraq; and the second in the centre of Iraq with the exile to Babylon in 587 BC. The Jewish communities in Iraq lived with no temples and no king but they had the Law, the Torah. Their prophets played a major role in the birth of Christianity. After the return of the exiles, the Jewish schools in Mesopotamia developed a decisive vein of prophetic and biblical thinking. We believe that two-thirds of the Old Testament were written in Iraq.”

Monumental heritage: “Iraq has around one million archaeological sites, of which only 10,000 have been explored. Imagine our prosperity if we were only to look under our feet! There are traces of a human presence in Iraq dating back to the 7th and 8th millennia BC, with the major civilisations such as the Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Arameans, Christians and Muslims (…)

The fanaticism of ISIS is futile. One cannot hide the sun. The heritage of all Iraqi cultures cannot be destroyed by a bunch of fanatics over three years.

The consequences of the destruction of Christian heritage monuments are extremely serious but this may also increase awareness of the value of what has been lost.

They destroyed the Jonas mosque (Nabi Younès) in Mosul which used to be a monastery and before that as an Assyrian castle in Nineveh. They tried to remove all trace of Christian existence, but I think this will turn against them. Indifference is more damaging that fanaticism. The current generation and generations to come will need to heal the indifference cultivated by the previous generations.”

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute